For heterosexual young women processing their first flashes of pubescent yearning, a lethal paradox lies in wait. A man can be the most desirable thing the imagination can conjure, want itself made pure and human, a fantasy potent enough to dominate all waking thought and dictate just about every choice a teenager makes. All it takes is one unsettling moment, however, to remind these same budding women that the men they lust after can harm them.

The warring impulses that define early adolescence – an excited curiosity about a much-touted sexuality, mixed with trepidation about the adult and unfamiliar – take on graver stakes with girls, forced as they are to safeguard themselves against a masculine culture of predation and violation. It’s a standard bullet point for distaff coming-of-age movies to hit; think back to how quickly Eighth Grade‘s car scene pivots, as thirteen-year-old Kayla goes from feeling cool while riding unsupervised in a car with a boy to fending off his advances in a matter of moments.

Joyce Chopra’s 1985 feature debut Smooth Talk situates itself in the anxiety between a bracing carnal freedom and the chilling awareness of its hazards, then raises the tension to an unbearable intensity. To the director as well as Joyce Carol Oates, writer of the short story on which the script was based, the essence of maturing lies in the hot-running fear that must accompany irresistible horniness. The film’s first half gives us one of cinema’s most indelible images of a boy-crazy girl’s initial flirtation with, well, flirtation; like a theory’s corollary, the second pulls the inevitable 180 into a standoff with the personification of the evil that men do.

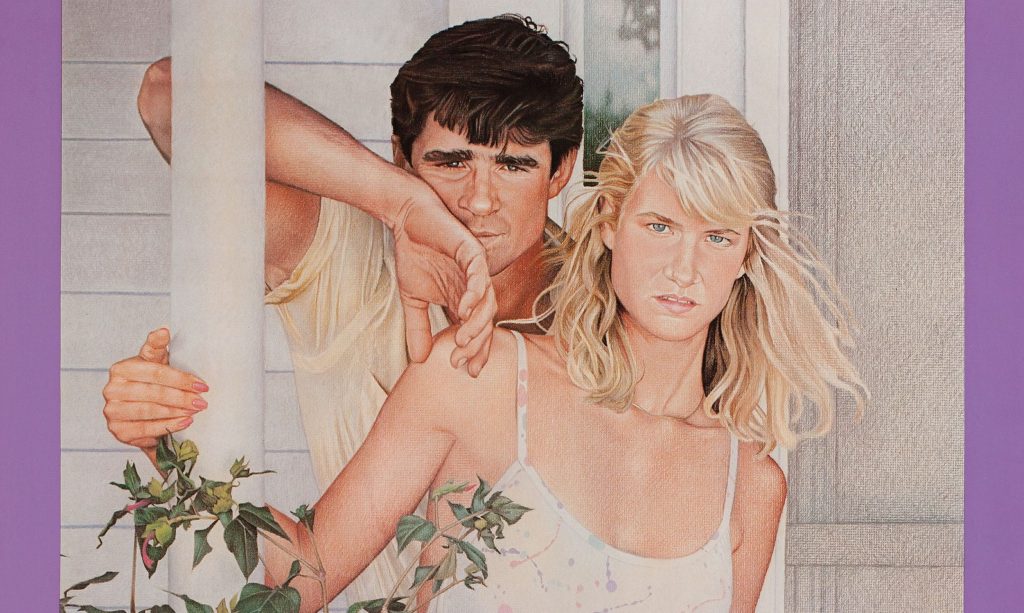

At the tender age of eighteen, a largely pre-fame Laura Dern was ripe to embody the coquettish precocity of Connie Wyatt (three years junior to the actress playing her). She gave a star-making turn in her first go as a lead, mesmerizing with her teased-out hair and suggestive bodice-by-way-of-Lisa-Frank halter top. A fount of confidence, Connie prowls through the mall and sizes up the local guys through eager eyes, hungry even if she’s not yet sure what for. Chopra’s careful direction never shames the social butterfly for courting attention as she struts through the food court, instead sharing in the thrill of commanding someone else’s eyes, and possibly more.

But that’s only her outermost layer, an earnest front concealing the naïveté that rises to the surface at the first sign of danger. When she finally agrees to a date with one of the area boytoys, he gets handsy and she instantly shrinks up at this confrontation with the frank realities of sex. The brilliance of Dern’s performance hides in how easily she can drop the provocative exterior without making it seem like a facade she was putting on. Connie knows what she wants, and she does want it, but she didn’t know it would be like this. She wasn’t ready.

Her apprehension turns to outright terror at the midway mark, a transition all the more jarring and disorienting for its total formal disconnect from the rest of the film. The first segment plays like an unusually artful and finely detailed John Hughes project, toeing the line between the characters’ carefree school years and the grown-up world they’re barreling toward. The second is minimal, terse, and so frightening as to border on horror.

We’re as taken off guard as Connie is by the appearance of Arnold Friend, a James Dean-styled hunk of red-blooded Americana in the chiseled shape of Treat Williams. She’s has been left alone at home while her family goes off to a cookout, and he materializes in seeming response to her vulnerability. He should be the beefcake of her dreams, but their dialogue shivers with the insinuation of violence.

She speaks to him at length through the screen door, a flimsy symbol of how little control she has over this pas de deux (unless you count the goon in Arnold’s car who he occasionally screams at to pipe down, puncturing the snake-charmer spell he’s trying to cast). We don’t know what happens once he drives off with her and she returns a changed woman, but we can safely assume the worst.

Chopra’s direction, which emphasizes the constantly shrinking spaces that divide Connie from Arnold, turns this protracted unwelcome come-on into a duel with a malevolent, elemental force in league with Robert Mitchum in Night of the Hunter. This film deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as Charles Laughton’s classic, another work that puts the battle for a soul into mortal terms uncomfortably common. From what could’ve been dismissed as frivolous girl stuff – and was, by many at the time – we bear witness to a great reckoning between burgeoning womanhood and the society intent on consuming it.

The new 4K restoration getting a run in American virtual cinemas this weekend does a great service by boosting the profile of a major work from an artist who never got her due. Though Chopra completed her follow-up The Lemon Sisters in 1990 and her episode of Law and Order: SVU is superb, she didn’t get the fair shake she deserved in Hollywood, having spent the past decade in TV. Her triumph will now receive the platform it merits, and a new generation can find their place in an eternal conflict.

The new restoration of Smooth Talk premieres in the US on 6 November on Film at Lincoln Center’s virtual cinema.

The post Smooth Talk pits an adolescent Laura Dern against primal American evil appeared first on Little White Lies.