Puppets, Prosthetics, and Bubblegum: How They Did The Chest Chomp Scene in ‘The Thing’

Welcome to How’d They Do That? — a bi-monthly column that unpacks moments of movie magic and celebrates the technical wizards who pulled them off.

As far as gobsmacking creature effects are concerned, John Carpenter‘s The Thing is in a league of its own. It is the holy, gore-soaked church of sci-fi horror. And you can’t properly praise The Thing‘s FX makeup without paying dues to Rob Bottin, the wiz-kid heir apparent to the mentor-mentee lineage of Dick Smith and Rick Baker, whose abrupt exit from the industry in the early 2000s remains one of Hollywood’s great mysteries.

Bottin, a huge Halloween fan, met Carpenter on the set of The Fog. He was tasked with creating a number of make-up designs, including the worm-headed ghost who attacks Carpenter’s then-wife Adrianne Barbeau on the roof of the radio tower. After making a name for himself on Joe Dante’s The Howling, Bottin was brought on as the special makeup effects supervisor for The Thing, a tense Antarctic murder mystery about a group of scientists at the mercy of an alien presence capable of assimilating and imitating organic life. At the time, Bottin was 22 years old.

If you’re familiar with Carpenter’s films, you’ve actually seen Bottin before as Blake, The Fog’s spectral pirate leper antagonist. Bottin scored the gig by (1) having the balls to ask for it, and (2) being 6’6″.

At the production’s peak, Bottin was tasked with coordinating an army of thirty-five artists and technicians, including his lifelong friend, makeup artist Margaret Prentice and Ken Diaz, who Bottin jokingly dubbed a “purveyor of ripping flesh.” While principal photography only took three and a half months, shooting the effects for The Thing took well over a year, during which time Bottin lived and worked on the set at Universal. The demand for Bottin was concentrated and colossal, but he was committed — at his own expense — to bringing to life this monster who could look like anything in the galaxy and would never appear the same twice. The staggering workload, which he admits to hoarding, resulted in Bottin being hospitalized at the end of the shoot for acute exhaustion, double pneumonia, and a bleeding ulcer.

The Thing had the misfortune of opening two weeks after E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (interestingly enough, Bottin wore an “I love E.T.” shirt to promotional engagements). Critically maligned, The Thing did a box-office pratfall, wildly outgrossed by Universal’s more lucrative, optimistic alien blockbuster. At the time of its release, The Thing‘s special effects were simultaneously commended and criticized for being technically brilliant but visually repulsive. And yet, things change: the critical tide turned, and Carpenter’s bleak, paranoiac whodunnit/whoisit clawed its way to its rightful place on the genre’s top-shelf (where they keep the really good J&B whisky). Bottin’s work is now regarded as a milestone for practical creature effects, a gold standard for goo-slathered contortions of the human form mangled into terrible, imaginative, fleshy iterations.

And there is no swifter and more memorable demonstration of The Thing‘s practical prowess than the sequence in which Norris (Charles Hallahan) well…how to put this. During the group’s confrontation with a dynamite-brandishing MacReady (Kurt Russell), Norris, the station’s geologist, collapses and is hurried to the outpost’s emergency room. But this is no heart attack. And this isn’t even Norris. As Dr. Copper (Richard Dysart) brings down the defibrillator, Norris’ chest snaps open. Copper’s arms drop inside, and the cavity clamps down on the doctor’s outstretched forearms like an organic beartrap. A stalky mass erupts from Norris’ midsection, and flamethrower at the ready, MacReady incinerates the spindly abomination. Resourceful as ever, the creature’s head makes a break for it: stretching and screaming, tearing itself off its own shoulders and sluicing to the floor. The creature’s objective is the same as the human occupants of Outpost 31: survive. And in this case, survival means pulling oneself to safety with a flick of a bullwhip tongue, sprouting crab legs, and scuttling towards the door.

“You gotta be fucking kidding,” Palmer (David Clennon) moans. An accurate if hilarious exclamation, given that Palmer is revealed to be the Thing in the very next scene. But can you blame Palmer-Thing? That’s an awfully big bag of tricks to live up to! It’s a jaw-dropping chain of events, even on the umpteenth rewatch. That sudden, gaping, toothy maw. That intestinal, white-filmed mass of an appendage. That shrieking rip of jarringly vibrant green innards, packed into Norris’ throat like cable wiring. That impromptu crab leg getaway. You gotta be fuckin kidding. How the hell did Bottin and his team do it?

How’d they do that?

Long story short:

With manually operated and remote-controlled puppets, reverse photography, explosives, and a fiberglass hydraulic body cast. All live on set.

Long story long:

Most of the “chest-chomp” sequence was shot on an insert stage after principal photography had wrapped. In a manner of speaking, Norris’ chest really did open and it really did bite Copper’s arms off. As detailed in the making-of documentary The Thing: Terror Takes Shape, Hallahan spent ten days sitting for molds of his face and body. On the day of the shoot, after eight hours of makeup, he positioned himself inside the operating table with his arms, shoulders, and head exposed and blended into the mechanical fiberglass/foam-latex torso (devised by effects tech Archie Gillett). The “chomp” featured in the film is actually the second take of the stunt (the first pass produced a “Las Vegas” style fountain of blood that displeased Carpenter).

The “chest chomp” effect was achieved with a hydraulic mechanism that snapped the cavity open and shut, sinking razor-sharp acrylic “teeth” into two brace-supported replica arms made of Jell-O and gelatin blood tubes (for flesh) and dental wax (for bones). Double-amputee Joe Carone (sporting a mask of actor Richard Dysart) acted as a stand-in, pulling the false limbs back and providing one hell of a reaction shot.

The creature’s signature urethane tentacles were whipped from underneath the table by an operator, flicking horribly until small explosive charges send a geyser of green ichor (almost certainly some unholy blend of K.Y. jelly) soaring skyward. The stalk-creature is revealed: a suspended marionette operated by wires from above. Robert E. Worthington supervised the construction of six different “stalk thing” heads, each with their own range of radio-controlled expressions. The heads were maneuvered through a hole in the false ceiling — sneakily hidden through camera-placement.

The effect of the Norris-Thing’s head detaching itself from its body took months of testing before Bottin deemed it screen-ready. Half a dozen different Norris heads were sculpted and built, once again engineered by Worthington. While most of the facial expressions were radio-controlled, the eye movement was cable-operated (with a rig designed by Gillet). A puppeteer positioned under the table was able to move the head from side to side and control the mouth, which was augmented with extra facial expressions that were remote-controlled. The neck-stretch effect was achieved with a manually-operated steel shaft, concealed within the green, stringy innards of the neck itself, and pushed by an off-camera operator.

You can actually find some of more disgusting textures in The Thing in your local grocery store: jam, creamed corn, mayonnaise, carbopol (twinkie filling), and even offal. The stretching neck flesh was no different and was concocted out of bubble gum and melted plastic. Quick aside: a big part of why the rubber flesh looks so dang good in The Thing is that Dean Cundey, the director of photography, attentively lit the effects to hide their seams and give them an “alive” feel. Back to foam rubber: turns out, the fumes of heated plastic are quite flammable. As relayed in Fangoria #21, after the crew set up the shot for the head rip, Carpenter called for fire to be added to the bottom of the frame for continuity. After all, MacReady had just torched the Norris-Thing with a flamethrower. A fire-bar (a hollow, punctured, pipe supplied with gas) was set up, but the effects tech struggled to light it. When the bar finally did ignite, the operating table was swimming with butane and melted plastic fumes, and a fireball (eight feet in diameter by Bottin’s estimation) engulfed the puppet that had taken months of construction. Thankfully the effect suffered minimal damage and no one was seriously hurt. Truly, while most of The Thing‘s effects were designed to be done in one take, many required re-sets, which of course took hours.

The shot of the head’s descent to the floor was done with good old fashioned gravity (which I hear is cheap!) and Norris-Thing’s exploratory tongue-whip was accomplished with a reversed action shot of retracted cables. The head pulling itself by its tongue involved operators hiding beneath the desk, manipulating cables and translucent fishing line. The transformation where the head sprouts crab-like legs and exaggerated eyestalks took place on an elevated set with a phony floor, with operators below pushing everything up and out through the hollow head.

Now under the desk, screaming, the crab creature’s mouth and limb movements were operated with remote controls and cables. The final b-line for the door consisted of a fake head mounted on a radio-controlled car. The creature’s legs were fashioned out of thin aluminum tubes linked directly with the effect’s motor, which is to say: if the car sped up, so would the legs. Each leg was connected to camshafts (a machine element with linkages used to transform rotary motion into linear motion), which gave the impression of natural appendage movement.

What’s the precedent?

Before The Thing, there was The Thing From Another World, produced in 1951 by Carpenter’s hero Howard Hawks. While Carpenter frequently recounts how affected he was by the Hawks film as a child, he has always been adamant that The Thing is not a remake, but rather a different (and arguably more faithful) adaptation of John Campbell’s 1938 short story “Who Goes There.”

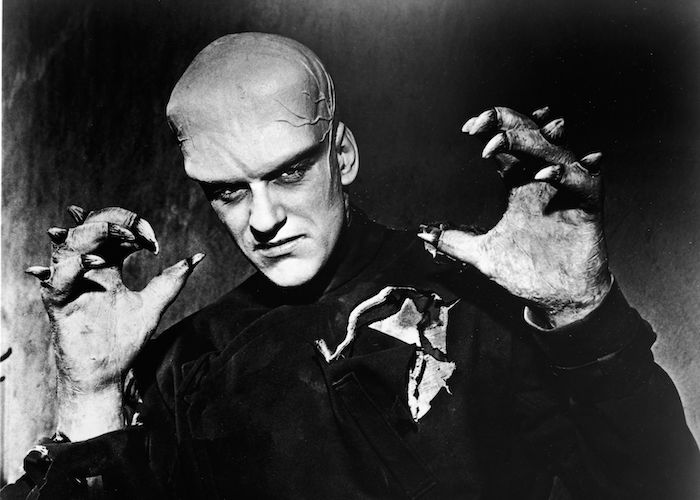

Carpenter’s affection for ‘The Thing From Another World’ on full display in ‘Halloween’

In the Hawks film, the titular Thing is recognizably human, in part because 1950s technology couldn’t write the special effects checks Campbell’s short story wanted to cash. Due to its limitations and budget, the titular Thing does not transform at all and is instead rejigged into a sentient, self-duplicating vampiric plant-based lifeform. Or, as Carpenter once put it: “a blood-drinking carrot from outer space.” In terms of its design, the 1951 Thing (played by Gunsmoke‘s James Arness) is really just a frigid Frankenstein without the pathos; a hulking golem with a raised forehead, rubber hands, and a jumpsuit. After forty-minutes of build-up, the film largely obscures Arness in shadow, a move Bottin would absolutely respect (when it came to lighting his creations, Cundy describes Bottin as “sensitive”). Shots of Arness’ imposing silhouette and the film’s impressive immolation sequence are when the creature is at its most effective. But, all told, the film doesn’t innovate beyond the simplistic standard of the time.

With the 1950s monster movies of his childhood (and Ridley Scott’s Alien) in mind, Carpenter was extremely concerned with avoiding a creature design that would read on-camera as “just a guy in a suit” This bugbear is, in part, why he encouraged Bottin to let his imagination run wild, as well as why he took solace in the chest-chomp scene. It’s a sequence that fails, at all levels, to register as human. When Carpenter first saw the finished product of the chest sequence, he felt, “A great sense of relief because what I didn’t want to end up with, in this movie, was a guy in a suit.” Well. I think we can safely say: mission accomplished, John.