If You Were Stoned in 1941, You Probably Watched ‘Hellzapoppin”

Cannabis isn’t the reefer madness your grandma made you believe! Welcome to Higher Education, a column that investigates – and destigmatizes – marijuana in movies and TV.

While cannabis has been consumed for centuries, we don’t have a lot of first-hand accounts of what stoners enjoyed doing while high before the 1960s, outside of what exploitation films like Reefer Madness would lead you to believe. And sure, who doesn’t love smoking a joint, putting on some hot jazz, and lindy-hopping the night away! But more specifically, what were the movies the dapper stoner of the 1940s enjoyed watching while baked? Surely Louis Armstrong and Bing Crosby had films they loved laughing at under the influence!

While cannabis innuendos had been peppered into early Hollywood films, like The Road to Morocco, there weren’t any films like the stoner comedies we know of today. But that doesn’t mean there weren’t films, like the 1941 musical comedy Hellzapoppin’, that shared many of the same tenants we come to expect from the niche subgenre. With an Adult Swim comic sensibility that leans on random, fourth-wall-breaking humor that’s absolutely dripping with talent, the ridiculous comedy in Hellzapoppin’ would not be lost on the modern-day stoner film aficionado.

But to understand why stoners would have flocked to Hellzapoppin’ the movie, you have to know a little about the original Broadway show. By 1941, the stage musical revue — created by comic duo Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson – was the longest-running production ever to be on Broadway, with three years and more than 1,000 performances. You could call it the Hamilton of 1939. Everyone who was anyone had to be seen at the show, from legendary actor John Barrymore to famed New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia. It spawned multiple touring productions, spinoffs (and knock-offs!), and eventually, after the original production closed, a major motion picture.

But the only problem with translating Hellzapoppin’ to the screen is that the original stage show was essentially unfilmable. Instead of a plot, theatergoers were treated to a mashup of vaudeville acts and rapid-fire jokes along with extensive fourth-wall-breaking audience interaction. Actors on stage would yell at shills in the house, while others would wander through the orchestra looking for lost children. One prolonged bit involved a man calling for a woman while hauling an ever-growing Ficus throughout the theater. After the finale, audiences were greeted in the lobby by the same man, now atop a 20-foot-tall tree, still hollering for “Mrs. Jones!”

The show also included various topical sketches, which meant it constantly had to be revised to reflect current events, like when World War II erupted a year after the show opened. This melding of slapstick and timely humor is one of the reasons it’s cited as a major inspiration for Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, another huge hit with the 420-friendly counterculture of the 1960s.

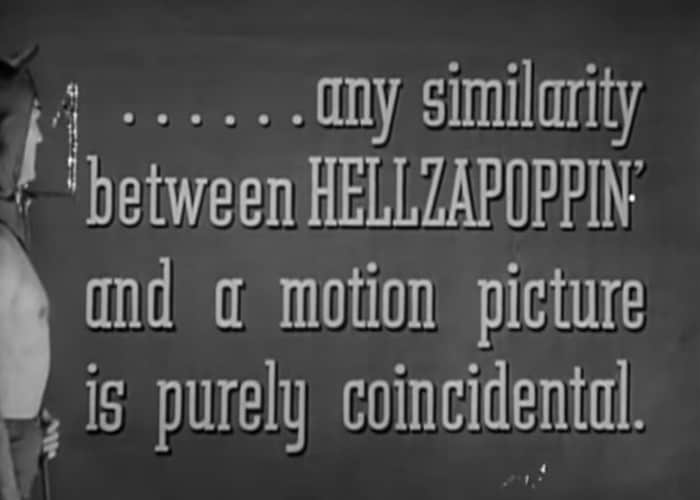

So, how do you translate a stage show with no plot and no script into a Hollywood movie? The short answer is: you don’t. The opening interstitials are pretty clear about that:

Rather than attempting a faithful adaptation, Olsen and Johnson, along with director H.C. Potter (Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House) and writer Nat Perrin (Duck Soup), decided to lean into the show’s chaotic nature and center the movie’s plot around how impossible the stage show is to film. And that’s exactly how Hellzapoppin’ the movie begins.

In the highly meta opening moments, a projectionist (played by Shemp Howard) loads a reel of Hellzapoppin’ into a projector, grumbling to the screen, “Fifteen years I’ve been running these pictures, and now all of a sudden I have to be an actor?” As the reel plays, we watch a line of showgirls descend into a riotous Hell filled with pitchfork-wielding demons as the title card appears on the screen. The camera then pulls back to reveal we’re actually on a movie set as Olsen and Johnson are in the middle of fighting with the studio over the direction of Hellzapoppin’ the movie. They think it should remain plotless, while the studio wants to wedge in a screwball romance because, well, it’s what you expect to see at the movies!

Rather than fighting further, they agree to hear the studio out, and the rest of the film is them watching – or technically listening – to that movie (the one the studio wants to make), which is happening in a movie (the one that Olsen and Johnson were in the middle of filming), within another movie (the one the projectionist is showing at the beginning), in yet a fourth movie (the one that we, the viewer, are actually watching!). And that’s just the first ten minutes!

But all that confusion and strangeness is exactly why I think it makes such a great stoner comedy. The tenets of the subgenre — outrageous humor mixed with outlandish images all aiming to blow your mind – are all here. From talking bears and disappearing guinea pigs, the zany humor practically speaks for itself, while the film’s gorgeous scenic design, like the fire and brimstone opening scenery to the lavish swimming pool sets for the film’s water ballet sequences, are a marvel to look at.

While it doesn’t exactly tick the “marijuana mysticism” boxes of the modern stoner comedy, I still think Hellzapoppin’ aims to blow your mind with how it completely obliterates the fourth wall in a way that cinema wasn’t accustomed to in 1941. Throughout the film, Olsen and Johnson actively talk to the movie-within-a-movie-within-a-movie’s projectionist demanding sequences be adjusted or rewound, even when it means they have to physically fight to stay in the frame. Other times, they’ll directly address the audience, flashing text reading “Stinky Miller, go home!” before the silhouette of a boy rises from a seat – as if he’s actually sitting in front of you – and exits the screen.

These kinds of gags would prove to be extremely influential over the next several decades to everyone from Joe Dante to Joel Hodgson. There are moments when Olsen and Johnson get a chance to kick back and watch the movie with you, providing their own hilarious riff track forty years before Mystery Science Theatre 3000 would popularize that brand of marijuana-scented humor. In Gremlins 2: The New Batch, there’s a scene in which the gremlins “destroy” the film reel you are watching before Paul Bartel and Hulk Hogan have to step up and save the day for your cinema. It’s these inventive moments of fourth-wall-breaking that’d make even the soberest of stoners say, “Woah, dude.”

Four years before Hellzapoppin’ was released, President Franklin D. Roosevelt would pass the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, the first law that would effectively begin cannabis prohibition in the United States. So if stoners wanted to get baked and go see the latest hits from Hollywood, they had to be a lot more sly about it, like turning their homes into what The New Yorker referred to as “tea pads.” We can only imagine how many pre-theater dinner parties or post-show spliffs were rolled at these makeshift social clubs so the hep stoners could fully comprehend the sensory overload of a movie like Hellzapoppin’.

But that’s all we have: our imaginations. We can’t say for certain that many people watched this film high because people in the 1930s didn’t talk about cannabis culture in the way we do today. But just because it wasn’t written about, doesn’t mean it didn’t exist. And with the tremendous energy, boundless imagination, and off-the-wall surreal humor, it’s clear to see that the wild spectacle of Hellzapoppin’ is a feast for the stoned senses – both present and past.