Joe Alves Sets the Record Straight on the Supposedly Inoperable Shark of ‘Jaws’

Welcome to World Builders, our new ongoing series of conversations with the most productive and thoughtful behind-the-scenes craftspeople in the industry.

Before Jaws, and even after Jaws, the idea of a giant killer shark movie belonged to the territory of disposable trash cinema. The concept was fit for oglers seeking cheap thrills strapped within teeny B-movie bikinis, but no self-respecting artisan would dirty their hands with such salacious chum. Enter Peter Benchley‘s first novel, which was already making waves (sorry, not sorry) in the publishing world prior to hitting shelves and sparked cinematic possibility when producer David Brown stumbled across a plot description in Cosmopolitan, which at the time was edited by his wife, Helen Gurley Brown.

Benchley was a well-regarded journalist and speechwriter, and he tackled his fiction with the same level of research and respect that he would his previous reporting. Once his curiosity was struck by the real-life 1964 great white shark attack off the coast of Long Island, he tackled the material with tremendous sincerity. Every other creator who touched Jaws going forward acted in the same manner.

Joe Alves was one of the first talents to join the adaptation after Brown and Richard D. Zanuck secured the option. At the time, he was working as an art director on a few TV movies, Rod Serling’s Night Gallery and Steven Spielberg‘s first theatrical feature, The Sugarland Express. Brown sent Alves the Jaws galleys and asked if he could whip up twenty to thirty illustrations to aid them during pitch meetings. Oh, and, uh, they couldn’t technically charge his time either. He’d have to squeeze it in.

One does not simply “whip up” twenty to thirty illustrations, especially when they’re working around the clock on several other projects simultaneously. In the morning, Alves would check in with the art department on Double Indemnity (the TV version), and at night he’d plug away on designing Jaws. He plowed through the novel, highlighting the action sequences, and did his damndest to accentuate the terror of each situation.

“The first illustrations sometimes looked like Moby Dick,” says Alves. “I was just trying to get into the action. There’s some stuff with the little kid in the shark’s mouth, coming at the camera, but it was a growing process.”

At no point did he think he was working on some cheap creature feature. The novel used horror to accentuate character and never allowed the sharp-toothed external factors to overwhelm internal struggles. Alves’ determination came straight from Peter Benchley.

“I’m reading this book,” he says, “and I’m getting into this island community with all this stuff centered around ‘You gotta close the beaches,’ and the shark comes up again and again. I did a little research on white sharks, but not until the movie was official did I contact Leonard Compagno at the Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco. Then I got into the details of white sharks and what they do, and I finally saw Ron Taylor and Valerie Taylor‘s Blue Water White Death documentary. I just grew into it.”

Spielberg did not initially pursue Jaws as his next feature following The Sugarland Express. He was determined to make a swashbuckling pirate adventure, but Alves kept popping over to the director’s cabana on the Universal Studios lot and sharing his Jaws illustrations.

“He was still thinking about doing a pirate movie,” says Alves, “but he had some ideas, and he said, ‘Boy, you know, if only we could do it with a big full-size shark and no miniatures. A 25-foot shark in the real ocean!”

If he couldn’t get this pirate movie off the ground, maybe Spielberg could scratch the same itch with Jaws.

“We both had seen The Old Man and the Sea with Spencer Tracy,” he continues. “The marlin in that film looked really bad. It was in a tank with a backdrop. Steven said, ‘God, we don’t want it to look like that. We have to shoot it on the real ocean and in full-size.’ Well, I guess we were a little naive as to how difficult it was going to be shooting in the real ocean, and how much time it would take to make the shark.”

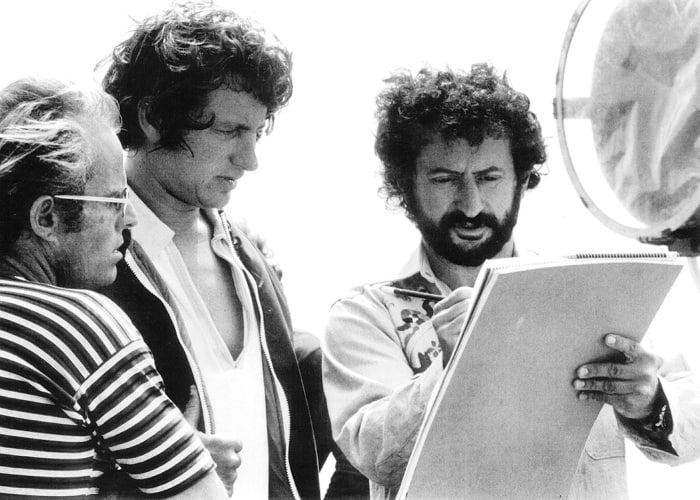

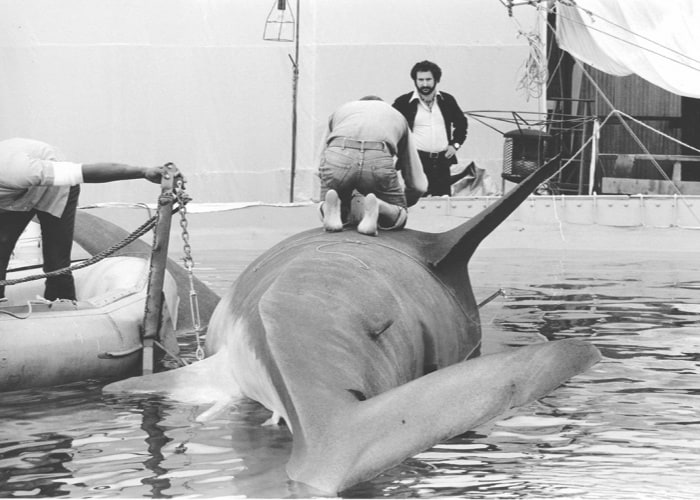

With Spielberg on Jaws, Alves moved into the role of production designer, taking on the responsibility of bringing not just the world of Amity Island to life but also the damnable beast at the center of the film. Much fury and fervor has circled the supposedly disastrous construction of Bruce the Shark, named so after Spielberg’s lawyer Bruce Ramer, but Alves takes offense at such misinformation.

“The studio didn’t want to make the movie,” says Alves. “To them, it was just a shark movie, but Zanuck and Brown were heavyweights. I think if they were writers/producers, they probably would have canceled the movie, but because they did The Sting and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, they had a lot of power, and we were able to continue. Steven just had to shoot everything, every walk-and-talk, without the shark.”

With little time, Alves and his team created miracles. It wasn’t that the shark didn’t work; it was merely that the shark didn’t work yet. Scramble was the name of the game.

“It was amazing,” says Alves. “These guys in the effects department were unbelievable. Roy Arbogast and Bob Mattey worked seven days a week, twelve hours a day, doing this thing. We built [the shark] in Sunland, which is the valley here in Los Angeles, and then we shipped it to Martha’s Vineyard, where they tried to test it in saltwater. Well, that was a big problem. Saltwater and electronics don’t mix too well, do they?”

Three sharks were built: one to be shot left-to-right, one to be shot right-to-left, and the platform shark, which was used to lunge out of the water and attack. When one was acting funky, usually, another would be operational. Having drawn all of the storyboards, this allowed Alves to improv on the day.

“I would go to Steven,” he explains, “and say, ‘Let me see what Bob has that’s working.’ Well, according to Bob, the left-to-right is working. Steven would look at the boards, and he’d say, ‘Okay, let’s do 185 A, B, and C.’ If it worked, we shot it. If it didn’t, it was a test. And basically, that’s how it was done shot by shot. It was really hard. Nobody to blame except maybe the studio.”

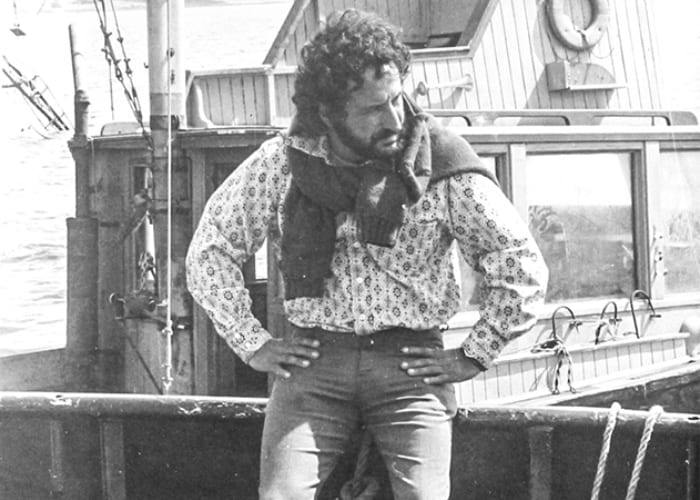

Amongst all that flurry of construction, Alves also made his directing debut on Jaws, shooting second unit on one of the film’s most horrific sequences: the death and devouring of the young Kitner boy, who goes out screaming in a geyser of blood.

“Oh God!” he shouts in remembrance. “That was so difficult! We were shooting into the bay, and it was so foggy. I had to use radar to see if I had the shark in the correct position, and then we had to put the dummy on a little raft to float, and then the sun came up, and the shark came up, and it was right. I wanted to shoot it with the sun right behind the shark, and then the effects guy jumped in, and he says, “Oh, I just got to tie-” and I said, “No, No! Get out of there!”

Recalling the memory, you can hear the excitement and frenzy of the production return to Alves as if he were back in the water.

“I just wanted to see the shark coming up with the fin and the sun blasting against it,” he says. “It was my first time directing, and Steven was exhausted, and he wanted to get back and start cutting the film, so he asked me if I could take that shot. I said, ‘Of course, I’ll do it.’ To say the least, it was difficult, but it worked.”

From that one uncredited gig on Jaws came his official double-duty work as production designer and second unit director on Jaws 2, and from there, he took on the mantle of director for Jaws 3-D. Ah, but that’s another story and another shark with a wholly different set of problems altogether.

You can now celebrate the 45th Anniversary of Jaws by purchasing the new limited edition 4K Ua HD. All photos for this article provided by Universal Pictures.