‘The Final Comedown’ Offers Wisdom, Bloodshed, and Angry Catharsis

Welcome to The Prime Sublime, a weekly column dedicated to the underseen and underloved films buried beneath page after page of far more popular fare on Amazon’s Prime Video collection. We’re not just cherry-picking obscure titles, though, as these are movies that we find beautiful in their own, often unique ways. You might even say we think they’re sublime…

“Sublime /səˈblīm/: of such excellence, grandeur, or beauty as to inspire great admiration or awe”

The urge to watch movies that are entertaining and unchallenging in these grim times is overwhelming and normal, but I tend to go the opposite direction. I’ve gotten better since the terror attack on the Parisian concert venue in 2015 sent me into a four-hour spiral of increasingly violent and grisly YouTube videos — look, we all deal in our own ways — but I still typically turn towards dark entertainment when trying to smother real-world horrors.

All of which is to say that I’m drawn toward movies like The Final Comedown (1972) in response to ubiquitous news stories and cell phone videos highlighting police atrocities, the overwhelming abundance of which are committed against Black Americans. This early 70s feature tackles the problem head on and highlights the sad truth making the film timeless for all the wrong reasons. Nearly fifty years later, and this “great” country of ours still hasn’t gotten its shit together on a very simple premise — Black lives matter.

What’s it about?

Johnny Johnson (Billy Dee Williams) is a young man pushed to action by a country unwilling to grow up and do better by its citizens. He’s harassed by cops on the streets, he loses jobs due to racist bosses, and the only way he sees to survive is through fighting. Together with friends and like-minded associates he forms a radical group along the lines of the Black Panthers — they’re never named, but the idea is familiar — and as the film opens they’re embroiled in a running gun battle with hundreds of the city’s police officers. Johnny’s shot leaving the others to fend of the cops and secure medical attention for him, and as all of it unfolds the film moves into flashbacks from the perspective of various characters.

We’re made privy to the conversations and police transgressions that led Johnny to this life, we see how a group of young, White liberals attached themselves to the cause even as they fail to comprehend the cost, and we watch older generations — both Black and White — argue for complacency over action. Each time we return to the gun battle, more bodies fall on both sides, and by the time the credits roll the streets are running red with the blood of Blacks, Whites, and boys in blue.

What makes it sublime?

Williams’ script is inspired by Jimmy Garrett’s play, We Own the Night, but while there’s evidence of an origin on the stage to be found here in some of the main setups and character interactions, the film finds its cinematic footing in various violent set-pieces. Dozens of cops and radicals alike are shot to death with several falling off roof tops or out windows, and the action is all done on a no-frills budget — some with squibs, some without, it doesn’t matter — propelled by an electrifying jazz-funk score from composer Wade Marcus and musician Grant Green.

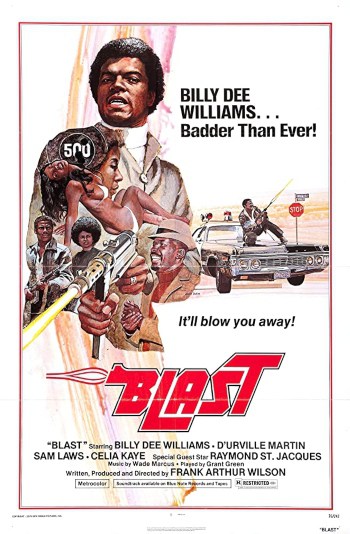

It’s an ua-low budget exploitation movie — Roger Corman himself reportedly contributed a whopping $15k towards the production — as evidenced by the poster (showcasing the film’s alternate title, Blast) working hard to get butts into seats, and it’s arguably an early entry in the so-called blaxploitation genre. It feels more in line with something like The Spook Who Sat By the Door (1973), though, as it’s a call to arms rather than entertainment with romanticized, heightened, or exaggerated anti-heroes as lead characters. These are everyday Black Americans, and Williams reminds viewers of that each time his film pulls away from the action. Johnny’s antics seem extreme to some including his mother and some White friends’ parents, but his litany of frustrations and growing hopelessness is laid bare through glimpses of the racist world he’s a part of.

The film’s main target is the police, obviously, and Williams’ script pulls no punches on that front as we witness abuses both minor and murderous at the hands of the cops. Their transgressions are the key instigation leading to the central gun fight of the film, and Williams doesn’t shy away from showing them brutalized and gunned down too. The end is inevitable, but getting there is a long, drawn-out fight with massive casualties on both sides, but if it’s somehow unclear where Williams’ allegiance sits look no further than the scene of a cop being shot through a window causing his face to slide down the glass leaving his nose resembling that of a certain barnyard animal.

“If we have to die,” says Johnny, “then let it be so that the language of the young brothers and sisters behind us can be the dialogue of living men.” He’s as sincere in the belief that things can be better as he is that getting there requires bloodshed, and it adds an additional layer of tragedy into the film’s theme as this isn’t a war he chose to fight — it’s a war he has to fight. Not everyone agrees with his methods as some within his community suggest “It’ll work out, just give it time,” while a young, well-meaning White woman offers that he could just drop out of society to avoid its expectations. “We can’t drop into nothing because we never had nothing to drop out of,” he replies, adding that her only hope at understanding would be if she could wake up Black on Monday morning.

No mere action movie, this is a film fueled by emotion and rage with themes that in a better world would be seen as historical instead of evergreen. It suggests that no group (outside of the cops) is a monolith — some Blacks disagree with Johnny, some Whites support his cause — while insisting that it’s a problem that can’t be solved without unity, understanding, and support from all directions. The film’s ending isn’t very optimistic in that regard, but recent events in the real world suggest that the tide might actually be turning.

And in conclusion…

“My dad died fighting Nazis,” says one of Johnny’s friends, “but he died fighting the wrong ones.” It’s an insanely powerful and sadly prescient line as half a century later the fight against racially fueled police brutality and the abuses of a system that devalues Black lives continues on a daily basis. As raw and clunky as the film is at times, as clear as its low budget is, there are moments, dialogue, and sequences of absolute beauty and power. One example sees armed Black men and women reciting lines from the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal,” they say in unison, and it’s a reminder that no matter how eloquent the words, it’s ultimately action that gives them power.

Want more sublime Prime finds? Of course you do.