The Harrowing and Hypocritical Humanity of Folk Horror

Welcome to Carnage Classified, a monthly column where we break down the historical and social influence of all things horror, then rank the films of each month’s category accordingly. Franchises, movements, filmmakers, sub-genres, etc…It’s all here! This entry is about folk horror films.

Is there anything more horrifying than the ominous suggestion of what lurks around your home and beneath your feet, completely hidden until you’ve stumbled into its adamant clutch? Folk horror isn’t defined in absolutely concrete terms. It has an ever-evolving set of characteristics. However, it’s most aptly recognized by its utter isolation. Usually set in a rural location, folk horror is marked by either the dark spiritual power of the land, a community that exists on the fringe — with their isolation breeding a “wayward” set of beliefs, religions, and practices — or both. Nature’s familiarity is rendered eerie and untrusting. It all rests on the terrifying assertion that the familiarity of the land and people who surround you are a grim mystery with dark, damning truths.

Despite its popular resurgence in the past five years, with such films as Midsommar (2019) and The Witch (2015), the 1970s were the heyday of folk horror films. Some people credit the subgenre’s impetus as a reaction to the philosophy of the hippies, renouncing modernity and preaching “back to the land” practices. Even further back, it’s traced to Celtic paganism and the push against organized forms of religion in favor of independent worship. But to look at the culture and output of Hollywood, it might be compelling to think of the 1968 Tate-LaBianca murders executed by members of the Manson Family. The brutality of the events didn’t only terrorize the city in which they took place but frightened all of America, inspiring fear of isolated communities and a wariness that established the Satanic Panic that hit full force in the 1980s.

When looking at major horror films of the 1970s, the folk horror subgenre ran parallel to the films that set the stage for the occult obsession in the genre at large: The Exorcist (1974), The Omen (1976), and The Amityville Horror (1979). And beyond the subgenre’s prevalence that decade, it also reared tremendous influence in films of the decade that are not primarily categorized as folk horror, including The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977).

Landscape is integral to folk horror films, as these communities often inhabit spaces that are naturally isolating or easy to hide behind. Their enigmatic existences allow for an escape from society’s stronghold and the morals, values, and lifestyles that are gripped within its fist. Often they are earthy Edgelands: atmospheric and somehow seductive. They’re reminiscent of lauded art museum paintings, despite a present, persistent suspicion that doesn’t afford a bypass on account of beauty. Instead, the romanticism of these idyllic landscapes is savagely spaded to unmask the macabre that dwells underneath.

For this entry, I look at five folk horror films that span from the 1960s forward: Viy (1967), The Wicker Man (1973), Children of the Corn (1984), The Village (2004), and Hagazussa (2017). Each of these films covers the wide array of folk horror’s definition: the psychic power of land, the rejection of modernity, varying belief systems at war, and the influences of spirituality on both the cult and the individual level. To observe folk horror films and account for their lasting similarities as it bridges these decades — from just before its prime and into current times — is a sobering look into the ageless atrocities that humanity’s hypocrisy perpetuates.

Onto the ranks! Spoilers ahead.

5. Children of the Corn (1984)

Small town USA communities usually feel swaddled in a blanket of feigned safety. There are no large populations, no heavy police presence needed. Everybody knows everybody, so what secrets can possibly thrive? In fictitious Gatlin, Nebraska, this isn’t the case, at least not anymore. Children of the Corn, based on Stephen King’s 1978 short story, follows a community of children who murder every adult in town through a youth revolution. They fall under the authoritarian rule of Isaac, a messiah of the deity “He Who Walks Behind the Rows,” and his primary enforcer, Malachai. Residing in the tall grass of the cornfields, Gatlin appears to be unoccupied. But when Burt and his girlfriend, Vicky, can’t manage to avoid winding up in what they believe to be a ghost town, they soon find that they’re interlopers in a place where their very existence is forbidden.

The first scene of the film reveals that Gatlin has had a bad corn harvest, and it’s the solution to this issue which spawns the town’s transformation of population and power. Isaac tells the children they must appease He Who Walks Behind the Rows, holding the fields as sacred ground and sacrificing the adults in his name. The adults were turning to prayer instead. Namely, “the Blue Man” (a police officer), knowing of the demon that was holding the crop hostage, planned to set the fields alight. He was later crucified by the cult, an act that mirrors, or perhaps mocks, the beliefs he thought would save him. Later in the police station, Burt sees a frame of badges vandalized in red with the words “NO FALSE GODS.”

These conflicting dynamics of belief — the opposing gods of which the two groups worshiped — are the root of the human dilemma within the film. This proposes an interesting argument regarding varying beliefs and practices within a society and the actions one group takes to set their own as the primary. It’s an issue that doesn’t exist solely in small communities but in the world at large.

The youths leaning into paganism has the traditional fixings of any cult: a messiah, hierarchy, isolation, and the manipulation of malleable minds. It’s corruption. Yet, it’s also suggested that the land itself has been bastardized, too. Only the destruction of He Who Walks Behind the Rows can return it to its most organic state. Just the same as the existence of the appropriation of all religious imagery in the town — with magazine cutouts layered over photos of Mother Mary — the original content still lies beneath its invader.

Children of the Corn is undeniably hokey, yet it is entertaining nonetheless. Despite it finding its place at the bottom of this ranking, it’s still a film I thoroughly enjoy. That being said, it introduces a lot of potential themes but doesn’t fully adhere to them. However, it still cleverly addresses the fear of debating ideologies, spiritual power uninhibited, and the unreliability you may encounter among the only humanity you can manage to find.

4. The Village (2004)

M. Night Shyamalan’s filmography has always been polarizing, but I am among the group who quite enjoy his films. Particularly, I am one to defend his 2004 folk horror-thriller, The Village. The film straddles an interesting dichotomy between the known and the unknown by introducing a suspicion that there’s ground to be found somewhere in the middle.

The film tells the story of an isolated community out of time. Surrounded by dense woods of which they are fearful, the Elders warn them of the dangerous creatures that lurk within. The village knows nothing but each other. The woods and the world beyond are completely unknown to them. However, when the man that Ivy Walker (Bryce Dallas Howard) loves is in dire need of help, she, and she alone, is allowed to travel through the woods and to “The Towns” in search of medication.

The Village is a tale about modern escapism, “back to the land” philosophy, ethnocentricity, and the utilization of fear as a control tactic to render society into compliance. The community lives on their own agriculture, their own hierarchy of power, and without technology. It’s posited to be in 1897, but in reality, it exists in the modern day, cut off by dense forests and high, impenetrable walls. The Elders wished to escape the moral turpitude of modern society and all of its corruption and crime, vying to build their own utopia instead. Utterly isolated, it is the perfect environment for totalitarianism to thrive.

Terror is constructed to keep the citizens in submission: fear of the color red, preaching that the forest is brimming with savage beasts, and titling all other communities as “wicked places where wicked people live.” It’s fascism. Every decision is made by the Elders. It’s only when Lucius (Joaquin Phoenix) requests to leave, to fetch medicine for an ailing boy, that physical “monsters” show up and terrorize the community into sheltering in. Of course, these monsters are simply Elders in disguise, or Noah (Adrien Brody), a mentally disabled man who is exploited by those in power as a pawn of panic.

The Village exemplifies what happens when authoritarian leadership, thriving on solitude, overrides its people for fear and idealism. One of the Elders allowed his own son to die of an illness that was entirely treatable by modern medicine in order to maintain the power they hold sacred. Lives are permitted to be lost for the sake of not disbanding the domination they’ve accrued. The whole-hearted, visceral rectitude that the Elders feel is horrifying. In their bones, they believe the world they’ve created is worth the harm. It’s an anti-capitalist, anti-wealth, anti-drugs, anti-guns, anti-violence society, and yet, among this liberation from modernity, there’s not a shred of freedom to be found.

The Village woefully inquires into the world’s various power systems, begging us to examine, with a more prying eye, whichever one we exist beneath. It weighs the line between protection and captivity, and reminds us to reconsider all that we think we know: is it possible that we’re unknowingly ignorant? Maybe even willfully stagnant?

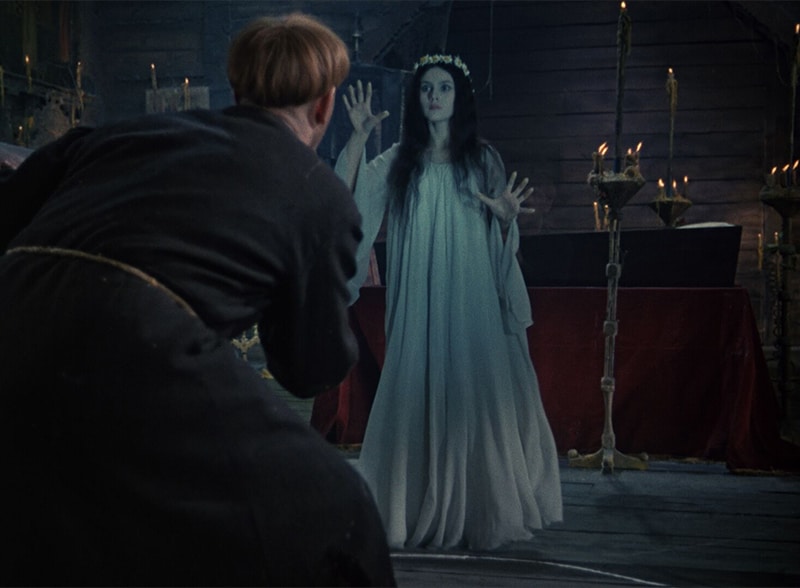

3. Viy (1967)

Righteousness isn’t easy to maintain — for anyone. We respect upright behavior from everyday people, but it’s an unforgiving expectation for those in religious power and influence. Viy tells the story of Khoma (Leonid Kuravlyov), a young seminarian who drunkenly murders a witch. But it turns out that he actually killed a young woman. On her deathbed, she requested him to keep her body safe from evil spirits, a task he must fulfill over the course of three nights.

Khoma is a monk in the making, but you’d never guess it. He’s rude, nefarious, and arrogant. When lost in the woods, he aims to take advantage of the kindness of an old woman as he looks for shelter. He promises her a reward from God if she helps him, but it’s an empty proposition and he knows it. He is brimming with hypocritical righteousness and blasphemy, using God, and his own status as a seminarian, as a means of manipulation. Khoma uses God as a tool, and when he isn’t doing so, he’s defying the behavioral standards of which a righteous monk would adhere. After the witch begins to haunt him in the night, Khoma’s calm and confidence is shaken. He doesn’t wish to perform the spiritual protection any longer, claiming he doesn’t have the looks, voice, or status, but is seduced by the “handsome reward” regardless.

He’s a drunkard, motivated by bribes, and swarming with hubris. He consistently praises scripture he doesn’t adhere to in the exact same moments that he defies it. His religion is something he falls back on only when it is of benefit to him. The witch requests him by name. It’s a smug test of his own faith. When entering the church for the first night of prayer, a villager reminds him, “Just remember. Pray in earnest.” As he parades within the church, still leaning into his blasphemous arrogance — drunk, bumbling, and smoking — the portraits of Jesus that line the walls don displeased expressions. There’s a nagging clarity that Khoma’s immorality is not unnoticed by any entity but himself.

Through it’s hallucinatory, fantastical storybook charm, Viy explores the genuineness and integrity of those whom society views as the most upright and reliable. It interjects the inherent corruption of human emotion and desire into the environment where they’re supposed to be under the most control. But above all, through its surrealism and hilarity, Viy permits an atmosphere of fun while its audience is compelled to look deeply into the hypocrisy and horror of their own humanity.

2. The Wicker Man (1973)

The Wicker Man is the first film I think of when I hear “folk horror,” and for good reason. It follows Sergeant Neil Howie (Edward Woodward), a devout Christian, as he’s beckoned to Summerisle in search of a young girl who has been reported missing. When he arrives, the citizens are coy, behaving with a tongue-in-cheek air of suspicion as they declare they have no idea who the girl is, saying that she doesn’t exist.

Equally dealing with macabre paganism and Christian ethnocentrism, The Wicker Man is an exercise in the observation of Western moral dominance. It takes Christianity and muffles it into the minority, giving the primary voice and perspective to a pagan cult’s set of beliefs. Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee), the community’s leader, is motivated by the purpose of rousing individuals out of modern, Christian apathy by giving them their “old gods” back. They fear and revere nature rather than a monotheistic figure, and their comments and conduct are frequently flippant and in ridicule of Christianity. As Howie and the cult are in constant opposition, the narrative introduces a slick, cyclical dichotomy between past and present.

Howie is horrified by the unbridled, shameless expression of sexual desire, as well as the sexual education that takes place in the school. To him, it’s all degeneracy — “fake religion.” Their self-described religion angers him, as the island has “ruined churches, no ministers, no priests, and children dancing naked.” Their paganism, by Christian point-of-view, is out of time, a sickening spectacle of years gone by. Yet, inversely, the cult believes the same about Howie’s religion. When looking through death certificates, he mentions that there are a number of names from the Bible, to which the clerk responds, “They were very old.”

Howie defines Jesus Christ as the “true god,” to which Lord Summerisle retorts that Jesus “blew it.” This insistent opposition of conflicting beliefs, of which neither side is budging, is never more prominent than in the film’s final fatal moments. Donned in a reminiscent white linen gown and led in a procession that hauntingly mirrors that of Jesus Christ, Howie is brought to his appointment with the Wicker Man.

Closed in its woven hold as he is set alight, Howie desperately prays to God as the cult circles around him singing. His prayers and the spiritual songs of the cult battle for authority, just as they have the whole film. Although this time, the stakes are mortal. The Wicker Man is a film about the self-indulgent intersection of religion and modernity. It exposes the harmful, ludicrous manner in which people base the empathy they afford to others solely on stiff standards. Through the tense, adversarial battle between Sergeant Howie and the people of Summerisle, The Wicker Man inquires into the validity, hypocrisy, and ambiguity of hierarchical religion, bringing forth a declaration that all belief systems exist on the same plane.

1. Hagazussa (2017)

A woman scorned. Maybe? It’s hard to know. Hagazussa is a 15th-century tale about Albrun (Aleksandra Cwen), a young, isolated woman living in a mountain village. She keeps to herself, as no one wants anything to do with her, and her sense of reality begins to devolve as she feels a cloak of darkness coming from the woods that surround her.

Hagazussa’s narrative is female-centric. Male characters exist, but only in fleeting bouts. The film’s main debate lies in whether or not Albrun is a witch and how the answer affects the way we perceive her life and the events that occur. Historically, witchcraft was a gendered attack on non-Christian religion and a simple way to target women with blind accusations. Albrun was raised by her single mother, who before her death was labeled as a witch. In her final days, she was overcome with deranged behavior; whether it was the workings of witchcraft or mental illness is unknown.

Flashing forward to Albrun’s adult life, she also has a fatherless child. Swinda (Tanja Petrovsky), a villager, relays to Albrun the fear of those who don’t carry God in their hearts. She states that heathens are approached by evil forces of which they bear children, cutting a jagged, incriminating eye at Albrun. Swinda uses her Christian moral high ground and persecuting tunnel vision to treat Albrun as less than. She even orchestrates her rape, bringing to light one of many possibilities as to why Albrun has a fatherless child. When the local priest calls her to remove her mother’s skull from the village ossuary, he says that its sacrilegious energy weakens the faith and corrupts the righteousness of the community. In both life and death, Albrun and mother are under the domineering clutch of organized religion.

Albrun plummets into insanity after her goats are stolen and slaughtered. She poisons the village’s water supply by tossing a rat into the stream and urinating on it. She returns home to perform a ritual on her mother’s skull. And later, she is vacuumed into a hallucinatory sect of reality after consuming a mushroom in the forest. This mushroom-induced psychosis leads to the horror that ensues: the murder (and consumption) of her child and visions of her mother that drive her out of her cottage. As she runs up the mountains and into the rising sun’s light, we see the film’s only hint of true supernatural influence. With her eyes glazed over in a milky white haze, Albrun lays in the grass with closed eyes and a smile as she spontaneously combusts.

Hagazussa is defined by its obscurity. Nearly everything is left up to our best guess, and that’s precisely where the horror lies. Was Albrun a manipulative witch? Or was she a victim to ruthless, misogynistic persecution that drove her heart and mind into oblivion? It’s not even clear whether or not she herself knows. Hagazussa uses Albrun’s 15th-century story as a mechanism to examine the timelessness of mental health, persecution, and dominant Western philosophy. It manifests how oppression carries through childhood to adulthood, and how the narratives pushed by the majority can slither and fester in the hearts and minds of its targets.

Pitting the past against the present and the physical against the spiritual, folk horror films are all about niche zealotries and the “civilized” individual’s anxiety of “natural order” left untamed and unmonitored. However, through these “civilized” anxieties is an inevitable sense of ethnocentrism, which offers an interesting debate to the foundation of the subgenre itself.

Of course, macabre paganism and societies out of time feel wrong from an outside perspective. But, until it affects an outsider, is it fair to condemn an existence based on the standards of your own? When intentions are unknown and actions not yet taken, there’s a dilemma of reliability on both sides of the conflict. Who’s to know who’s the threat? And when morality is dictated by varying cultural standards, how can it be fairly defined? If it isn’t a community, but the land itself, that serves as the vehicle of voracity, then the question begs whether or not we owe something to the Earth. What lies in the terrain we’ve built our whole lives on, and who holds the power? What does nature’s organic design permit?

In all its methods, the folk horror subgenre takes dark, unfathomable storybook tales and thrusts them, and the distrust of our surroundings, into tangible reality. Perhaps these stories aren’t for naught. Maybe they live and breathe, either in a far corner of the world or in an innocuous forest a mile away. I guess the distance depends on where you’re standing.