A Color Theory Reading of Olivier Assayas’ ‘Irma Vep’

In our new column Color Code, Luke Hicks chooses a handful of shots from a favorite film and analyzes them in detail to draw out the meaning behind specific colors and how they play into their scene and the film as a whole. Inspecting color is like inspecting the soul of a film. It’s an endless endeavor to better understand the artists’ intentions and our connection to the work. For his second entry, Luke digs into Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep.

Films about filmmaking are few and far between, and they rarely have much in common. Consider some of the most celebrated: 8 1/2, Singin’ in the Rain, The Player, Close-Up, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, The Aviator, Boogie Nights, Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, State and Main, and Ed Wood are all wildly different movies that address various aspects of the craft. Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep (1996) doesn’t get as much attention in the microgenre, but it’s as novel as the best of them, and it belongs in the conversation alongside them for a myriad of reasons.

Some of those reasons are more apparent, such as the dynamic all-timer soundtrack, or Maggie Cheung’s performance as herself, which requires more innate charm and charisma than it does trained acting chops. Or the ever-changing cinematographic landscape, which roams from Eric Gautier’s long, gorgeous 16mm takes to the unforgettable climax to actual footage from Louis Feuillade’s 1916 silent French serial classic, Les vampires. The keystone, however, is the metanarrative’s concerned commentary on the state of film and artistic liberation, which Assayas explores through such concepts as mimicry, visual obsession, and the abstract mechanisms of the film industry.

The movie follows Cheung in the titular role on the set of “Irma Vep,” (an anagram of “vampire”) a troubled remake of Les Vampires helmed by René Vidal (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a lauded French New Wave-esque auteur who’s lost his touch with age, as far as his crew is concerned. His motivations for directing “Irma Vep” are lost in a haze of madness and a sensual infatuation with an unflappable Cheung (costumed like Catwoman), and his vision for the film is at best confusing and at worst non-existent.

As the shoot hurtles forth, seams begin to tear among the crew. Economic, logistic, and artistic crises abound. Cheung remains rock solid as she’s pulled in every surreal direction by people’s desires. Conversations and meta-roleplays about varying approaches to cinema (from the perspectives of a critic, an actor, a producer, a director, etc.) ensue, but the tone is always satirical, even light at times. Roles blend, reality becomes difficult to discern, and the anxiety-ridden mystery over the film’s final form floats over everything.

The four shots below showcase the way Assayas uses color in composition to communicate mood, tone, and style, to draw out thematic concepts like repetition, chaos, and control, and to provide insight into systems of filmmaking and philosophies of art.

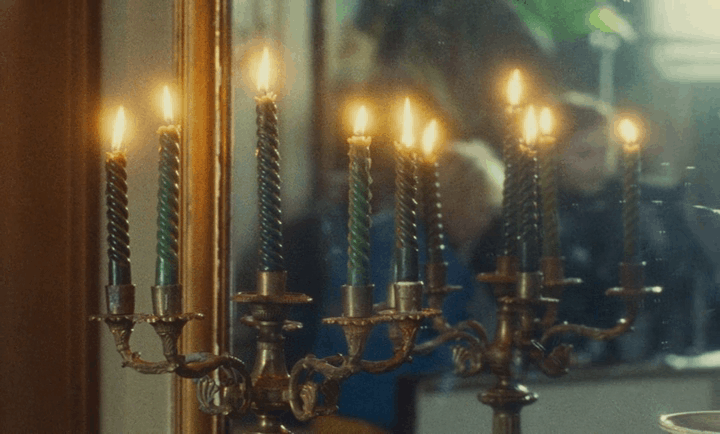

This decadent, layered shot comes early on and caps off a magnificent two-minute-and thirty-six-second single take that hovers behind the crew as if to examine their methods on the twenty-fifth take of a particularly difficult shot. It’s a rare long take whose clear purpose isn’t the length of the shot. Plus, it sets the stage for the magnificent camerawork to come. It begins with Cheung in character, passed out in a chair, and keeps rolling after the take-within-the-take cuts and the crew begins to reset for round twenty-six.

Vidal criticizes Zoé the costume designer (Nathalie Richard), who has a crush on Cheung and quietly delivers some more direction before approaching the candelabra, which is waved across a window as a signal before being set in front of the mirror. He tells the actor in question to wave the candelabra higher in front of the window before placing it “simply” in front of the mirror. The actor obeys the meticulous direction, but not without a chuckle and quick “this dude’s crazy” glance of affirmation toward the crew. Vidal scoffs.

The forest green, dim gold, and glowing yellow candlelight form an analogous color scheme, which means the three main colors are next to each other on the color wheel. Brown and blue creep from the side and the background. Loaded with meta-text, the mirrored image of the candelabra visually addresses Vidal’s and, vicariously, Assayas’ concerns with remakes, artistic repetition, and stale art. Gold is often associated with grandeur and success—the kind that defined Vidal’s career—but its faded quality signals his decline.

However, it still serves as the base that holds the candles (crew), whose separation and dark green shade spotlight the debilitating independence of the crew. Green is also commonly associated with envy, which all but envelops the shoot. Lastly, the butterscotch luminescence of the flames references the overarching theme of originality and innovation, specifically in regard to remaking Les Vampires, which is what Assayas is doing with Irma Vep and Vidal is doing with “Irma Vep.”

In a letter to Kent Jones, Assayas wrote, “The whole point is that the world is constantly changing and that as an artist one must always invent new devices, new tools, to describe new feelings, new situations.” Stanley Cavell calls these new devices “automatisms,” expressions born of organic and autonomous creation opposed to those steeped in tradition (e.g., most remakes) or a conventional mode of filmmaking (e.g., Marvel movies). If the flames of the candelabra represent the original film and its mirror image is the remake they’re attempting, think about its reflection.

We can tell we’re looking in a mirror, but the reflection is not a mirror image. It isn’t symmetrical, nor is it obvious which flame is which in the reflection. Some even blend together. The same goes for the candles and the holder. With the shot in question, Assayas creates a messy but original remake of the candelabra in the mirror. Vidal gives hyper-specific direction for the candelabra to create a visual metaphor, as if he’s Assayas lecturing his viewers on the idea that artistic repetition is stale without original interpretation, and rejecting predetermined systems of production is essential to discovering and exercising new modes of creation.

In this shot, we see Cheung being pulled away from Vidal after he’s passed out discussing his vision for the film mid-conversation. Cheung is with police and rattled producers on an emergency visit to Vidal’s home where he was having a mental breakdown. The deep red and dandelion yellow along with the shadowed orange of Cheung’s shirt are less significant for what they represent individually and more significant in their thematic dialogue with each other. Together, the analogous colors address the shoot’s chaotic nature and Cheung’s resilience in all of it.

The potential for havoc to erupt on a film set won’t come as a surprise to anyone who knows how films are made. The first time I was on a set, I realized what needed to be done to make the three-week shoot happen and felt absolutely certain we couldn’t do it, regardless of how hard we tried or how perfectly we worked. I was wrong, but such is the “magic” of filmmaking, which I’ll address later. From pre-production to distribution, hundreds, if not thousands, of people bounce around for months — or, more commonly, years — with hyper-specific tasks integral to the production’s completion.

The inescapably collaborative nature makes it so that every job hinges strictly on the others. Together, they form a tangled web of productivity that is the relentlessly churning motor of the shoot. That also means everyone must be prepared for the inevitability of human error, even if the error comes from on high, or happens to be the vision of the film itself. Unfortunately, the “Irma Vep” crew was not prepared for that grandiose an error. Enter: color.

The sharp contrast between red and yellow acts as a visual representation of the bitter dichotomy that is the crew. Also, notice how the candles from the previous image are like prison bars for the crew in the background. Dominated by their frustrations with each other and haunted by the ultimate vision of the movie, their only respite seems to be Cheung — poised, pure, and always professional — the one visual obsession most don’t have an issue with.

Orange is typically associated with wisdom and confidence, which Cheung wields in her mental and emotional temperance on- and off-set, where she’s always the belle of the ball. But orange is also a symbol of originality and artistic liberation. Where Vidal and his crew clash over their imaginations of the remake, Cheung is open and unbiased, willing to try new things and be stretched in the process.

Where color depicts the crew like oil and water, it presents Cheung as one solid color, a unified constant, the sole source of creativity that has the potential to energize the film and push it forward into fresh territory. Her insistence upon lack of control is what gives her so much of it. Vidal and company are tethered to their sexual objectification of her while she remains the only liberated party.

Likewise, they’re unwaveringly attached to their artistic convictions and comfortable systems of filmmaking, whereas Cheung is willing to change. She’s bound by their vision but free in her expression. It’s also worth noting that the dark coat hides her orange top, and in doing so acts as a physical representation of Cheung’s humility, her inclination to set down her own creative convictions in order to focus on something new, as Assayas would have it.

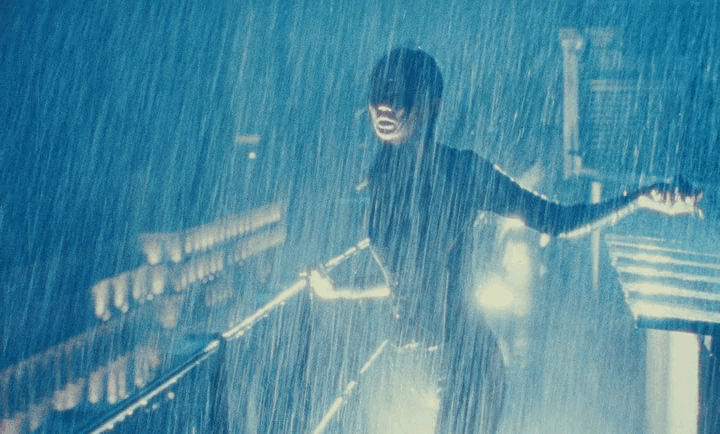

Within Irma Vep, Assayas presents multiple ways in which he could have remade Les Vampires differently. For example, the black and white shot-for-shot version, or the final experimental version. One of the most compelling versions also happens to be one of the most recognizable: a cool, dark, sleek, and sexy retelling that has the feel of a major studio remake in the twenty-first century. Unsure if the sequence is a dream, viewers are led to interpret the sliding scale of the monochromatic color scheme more like a sliding scale of shadow. Notice how Cheung’s face is half-skewed by shadow and half-spotlit, just as the rest of the frame is split unevenly between light and dark.

The meta-sequence begins with Cheung tiptoeing around the hotel as she does earlier as Vep in the film. She steals her stunt double’s jewel necklace and bursts out onto the roof in the pouring rain in her skintight black leather suit. Navy strikes various hues in the beaming light. The color, light, and shadow mimic the same monochromatic aesthetic from the Cheung-starring Hong Kong action film we catch a VHS-quality glimpse of earlier, and that’s not incidental.

In creating an imitative image, Assayas is making the point that the once novel way of Hong Kong action cinema, or any influential wave of filmmaking for that matter, is no longer novel. Original systems of filmmaking can sour into a normative system of filmmaking that leans too heavily on convention. In other words, too many people are making the same movie, and their aim is simply to copy their favorites, not create something new. Later on, a conversation about different systems of filmmaking plays out in an interview with Cheung by a French guy who apparently has his Master’s in Mansplaining Across Cultures.

He praises John Woo, asks Cheung about French cinema, rails against the old guard of the French New Wave, and obliquely bypasses her insertion that Woo is “better at working with men” while explaining to her that Hong Kong action is the way of the future whether she understands that or not. But Assayas isn’t shaming Woo’s style or exalting the French New Wave through Cheung’s open perspective. The two waves of cinema are stand-ins for any popularized mode of filmmaking. Assayas is pointing out that even the most original and profound automatisms in film — the French New Wave and Hong Kong action movements existing on opposite ends of the spectrum — can be made dull through repetition.

Through the lens of the modern thriller-esque vision, Assayas proves he could’ve made Irma Vep that kind of remake, and it probably would’ve been great. But he thinks artists are challenged to rise above playing the hits. In the same letter to Kent Jones, he wrote, “If we don’t invent our own values, our own syntax, we will fail at describing our own world,” a world that is always evolving.

The final shot is one of the countless metamorphic images that disjointedly flashes across the screen in the avant-garde film that Vidal edited before abandoning the production — inspired by Jean-Isadore Isou’s 1952 feature Venom and Eternity. Those that have seen it know the unfettered Lettrist chaos that defines the jarring climactic moment. That chaos can’t be captured in a single frame, because it relies on the blizzard of blurry, manipulated images in succession, but the single frame does give insight into how Assayas utilizes bizarre black and white cinematography to chew on the core question: Why do we do what we do if it’s already been done?

Vidal’s final brief cut is as genuine a search for artistic liberation as one could imagine on their road to the Irma Vep finale. Cohesive narrative development is out the window. Black and white circles, bars, spirals, and drawings flash feverishly over the film footage as the camera shakes and silence is occasionally erupted by bloody murder screams and distorted industrial sounds a la Death Grips. Any of the images from it could sit in this fourth spot. It isn’t their individual composition that makes them original — outlining a woman’s face is not new. Rather, it’s their part in the incomprehensible whole.

In this image, notice how the black outline around Cheung’s obscured face accentuates the artifice of the shot, but the darkness of her hair nearly subsumes the outline, making it harder to differentiate between the black of her hair and the black lines in her hair. It’s easier to differentiate in a still image, but when it’s a split-second flash, there’s no telling. Now, imagine a Hertzfeldtian level of chaos possessing thousands of frames in succession that all obfuscate their image with black and white markings.

Vidal’s “Irma Vep” is the ever-changing landscape of the world in experimental form just as Assayas’ Irma Vep is the same in its own original form. Its decidedly haywire and unsexy nature is a slap in the face to convention, an abrasive lift off into the unknown, and a chilling affirmation of one of Assayas’ many theses. This one is taken from The Medvedkin Group’s 1969 short, Class of Struggle: “Cinema is not magic; it is a technique and a science, a technique born from science and put in service of a will: the will of workers to liberate themselves.” But how can the workers find liberation in the art if the art isn’t liberated from systems of production? Perhaps they can’t, and that’s what makes Irma Vep essential.