How Does Rear Projection Work?

Welcome to How’d They Do That? — a bi-monthly column that unpacks moments of movie magic and celebrates the technical wizards who pulled them off. This entry looks into how rear projection works.

If you’ve seen a film from before the 1970s, there’s a very good chance you’ve already encountered rear projection. And if you’ve seen a film from before the 1970s with two people talking in a moving car, there’s a one-hundred-percent chance you’ve already encountered rear projection.

The concept is simple: Can’t shoot on real locations? No problem! Want to record on-set dialogue while your actors outrun the cops in a noisy convertible? Don’t worry! It’s as easy (in theory) as a sound stage and a projector.

At its advent in the 1930s, rear projection was a game-changing technology. It gave filmmakers more control, consistency, and creative freedom to shoot what they wanted where they wanted. And yet, while rear projection’s in-camera process effectively streamlined production workflows, it regularly failed to achieve any sense of naturalism.

Rear projection is, against its technicians’ best efforts, far from an invisible effect. Despite being the standard compositing technique for decades, with a few exceptions, rear projection never achieved a level of perfection such that its presence could go unnoticed. When there’s rear projection on the screen, it’s hard to overlook.

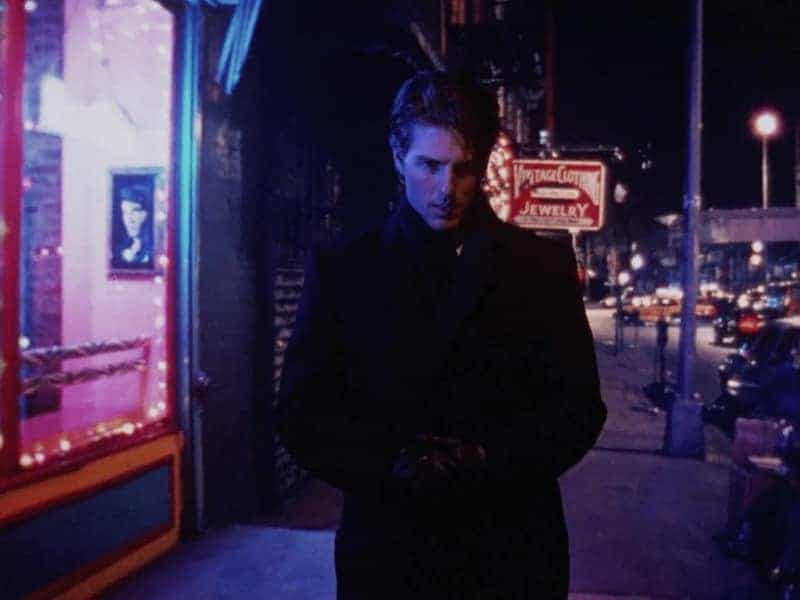

These days, rear projection has a reputation for being distracting and dated — an antiquated special effect that spoils the suspension of disbelief and never looks quite right. Over time, traditional rear projection morphed from a practical necessity to an expressive tool, a technique employed by stylish directors to revere or ridicule the past. Others have employed rear projection’s “off-ness” to convey a sense of unreality and unease, as with Neo’s first trip into The Matrix or Dr. Bill wandering the streets at night in Eyes Wide Shut.

While rear projection as it was originally conceived may have fallen out of fashion, good ideas always find a way to adapt and survive. So here we are, almost a century later, and despite all odds, rear projection is making a comeback. Here’s everything you’ve ever wanted to know about how rear projection works, where it came from, and where it’s going:

How’d they do that?

Long story short:

By projecting an image onto a screen from behind and then staging foreground action against its backdrop. The result, when photographed, is an in-camera composite.

Long story long:

Rear projection (a.k.a. process photography) was the primary special effects composite technology in Hollywood from the mid-1930s to the early 1970s. At its most basic, rear projection is composed of four components: a projector, a screen, foreground subjects, and a camera. The subjects are placed between the camera and the screen while a projector positioned on the other side of the screen projects pre-recorded footage or a still image. Typically, the aesthetic objective of rear projection is to create the illusion that the subjects are not on a sound stage. The technical objective is to make production more streamlined, safer, and consistent.

Rear projection background footage is called a “plate.” If you’ve heard someone yell “roll plate!” on a movie set — or a fictional depiction of a movie set — they’re basically shouting, “Fire up the projector!” When the projected background is in motion, it’s a “process shot.” If the background is a still image, it’s referred to as a “transparency shot.”

If your only experience with projectors is of the front-facing variety, you may be wondering: how does the light pass-through and stick on the screen? The short answer is that rear and front projection use different kinds of screens. Front projection uses an opaque reflective screen, which bounces light back. Rear projection uses a translucent screen that allows light to pass through while transmitting the light across its surface.

For the rear projection process to work, several holistic details have to be taken into consideration. For one thing: because the screen and the camera are fixed in place, all motion and angles must be accounted for by the rear projection photography team in advance. In other words: every movement and angle in principal photography must be carefully planned before the footage for the plate is shot.

The lack of Steadicam technology made this easier said than done. Matching the lighting on the soundstage to that of the plate is also critical. If the plate depicts a cloudless day and the actors are in shadow, the illusion will not work. Synchronizing the frame rates of the camera and the projector was also important. If one of the apertures was open while the other was closed, optical artifacts (like halos of light) would appear in the background plate and ruin the effect.

As Julie Turnock outlines in her essay “The Screen on the Set,” one surprisingly prevalent misconception about rear projection is that it is basically an old-timey predecessor of blue screen and green screen compositing. It’s true that the two techniques share similar aesthetic purposes. Namely: opening up the possibility of where and how filmmakers can shoot their subjects. But ultimately, both approaches have very different on-set and post-production specifications.

During its heyday, rear projection’s major advantage over other compositing techniques was its efficiency. The process could be completed immediately on-set at the same time as principal photography. It could also be shot in the presence of the key filmmakers and performers and assessed promptly in the dailies. Meanwhile, blue and green screen compositing is a part of a wider set of techniques that historically fall under the auspices of traveling mattes or “opticals.”

There is a crucial difference between optical composites and process photography: the bulk of the work for the former falls to post-production, while that of the latter takes place in-camera. The technical requirements of rear projection controlled many aspects of production, from blocking to mise-en-scène. And that sat just fine with the Henry Ford-ified conveyor belt of Old Hollywood.

In a fun twist. while conceptually rear projection is easy enough to explain and understand, in practice it’s very difficult to pull off in a subtle, seamless way. When people say “rear projection looks bad” they are usually talking about the same thing. Namely: that the technique tends to produce a visible difference between the foreground action and the rear projection footage.

Rear projection tends to look, in a word, “fake.” A part of the reason for this is that there is usually a discrepancy in the quality of the foreground action and the projected image. The characteristically washed-out, desaturated look of the projection is the result of a number of factors. These include print quality and projectors incapable of producing an image of sufficient brilliance.

There were fixes over the years, from fine-grain VistaVision film stock and more powerful projector bulbs. But a reliable methodology for eliminating the degraded image quality in the re-photographed plates never came through. As Turnock puts it: “rear projection was, in sum, perfectly consistent with the Hollywood studio production system, but not with its ideal seamless aesthetic.”

Front projection, the first mainstream use of which was in 2001: A Space Odyssey, solved a number of the problems of rear projection. The process involves carefully angled mirrors that allow the projected image to align with the camera’s focal angle and appear on a highly reflective screen, in-camera. The main motive for using front over rear projection is a noted improvement in image quality. Which, it turns out, makes all the difference.

As front projection and optical compositing became more affordable and accessible, rear projection became increasingly obsolete. There are very few directors today who earnestly never gave up on process photography, however. One of them is James Cameron.

Didn’t know there was vehicular rear projection in ‘Terminator 2,’ did you?

But, thanks to improved equipment, rear projection is back with a vengeance. For directors intent on shooting as much in-camera as possible, the promise of rear projection is enticing. Cutting edge technology like high-contrast 4K laser projectors have all but eliminated the distracting fidelity issues of film-based rear projection.

Not only is digital, pre-rendered, and real-time media able to achieve full photorealistic in-camera results, but filmmakers are also now able to add interactively cued elements at a moment’s notice. In addition to looking fantastic, live projection has the added benefit of giving the performers and the camera department something tangible to work with.

Joseph Kosinski’s Oblivion used front projection to convey an encompassing sky that reflects off spaceships and into its actors’ eyes. Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity placed its performers in the “Light Box,” a room full of LED screens that projected moving images onto their faces allowing animators to composite them perfectly.

And then there’s StageCraft (a.k.a. “The Volume”), a process Industrial Light & Magic honed in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story that uses a ginormous curved wall of LED screens powered by the Unreal Engine allowing for real-time display. The result is a virtual environment that can be rendered in real-time in the perspective of the camera.

The latest Star Wars project to use StageCraft is the Disney+ series The Mandalorian. And as executive producer Jon Favreau muses in American Cinematographer, StageCraft isn’t really rear projection but also isn’t really like anything else. And yet, amidst all this unprecedented tech, the practical purpose remains the same: by shooting everything in-camera, you reduce the time, money, and workload of post-production.

That StageCraft is able to make good on that promise in a way traditional rear-projection never cracked is exciting, to say the least. The ability to do real-time, in-camera compositing on-set means The Mandalorian is able to fill the tall order of being a live-action Star Wars television series — a small-screen project with a big-screen feel. Whether for television or film, the implications are exciting: that both production workflows and visual fidelity could improve in tandem.

Considering that back in the 1970s Star Wars’ use of optical effects was the supposed nail in the coffin for process photography, it’s somewhat poetic that the same franchise is pulling the technique back into the spotlight.

What’s the precedent?

In what is becoming a regular staple of this column, the idea for rear projection — by one Norman O. Dawn in 1913 — came way before the actual technique. Three unrelated technical developments in the 1930s made the technique possible: projectors that could synchronize shutters; better, panchromatic film stock; and more powerful projection lamps.

The first Hollywood studio to use rear projection was Fox Film Corporation’s Liliom in 1934. Appropriately, the film was subsequently recognized by the Academy for its efforts. The technique was then refined by Paramount Picture’s Farciot Edouart ASC, who developed new methods including brightening exposure and synching multiple projectors to the same plate.

The process became more standardized with a screen that had been specifically developed by Sidney Sanders for King Kong in 1933 that was not only bigger and more flexible but capable of supporting a higher quality image. King Kong‘s composition shots were optical effects, not process photography, but the improved screens they used were an important innovation for future process effects.

Rear projection is a special effect with a long past and a bright future. So next time you scoff at an Old Hollywood car two-hander: the modern incarnation of this technology is actually now being heralded as the future of television. So show some respect!