Dario Argento: The King of Giallo

Welcome to Carnage Classified, a monthly column where we break down the historical and social influence of all things horror, then rank the films of each month’s category accordingly. Franchises, movements, filmmakers, subgenres, etc. This entry is about Dario Argento’s giallo films and includes a ranking of his six best from the subgenre!

There’s something savory about a good murder-mystery. Even more delicious is when it’s delivered on a dramatic platter of theatrical intensity. So surely, Dario Argento’s filmography is a ripe source of sustenance. Though Mario Bava is credited with directing the first giallo film, 1963’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much, Argento is the man who took the deepest, furthest, and most popularized stab at it. When you hear the term giallo, you think Argento.

Giallo, meaning “yellow” in Italian, refers to the bright yellow book covers of Italian pulp fiction novels that centered their stories around elusive murders. It’s through this knotted connection that “giallo” eventually became synonymous with mystery. Though rooted in the history of the novels, there’s a number of core ingredients that comprise the foundation of making a giallo sensation on film.

For the base, it’s a murder mystery, so combine the killer, the killed, and those desperate to uncover the truth before they wind up on the wrong end of the blade. Mix in leather, bitchin’ bouts of bloodshed, psychological warfare, an unseen killer, and a club-worthy synth score (shoutout to Goblin). Finally, to garnish, regularly give the audience the killer’s POV, watch the body count rise, and relish in witnessing the over-the-top extravagance of the carnage unfold.

So, we got the basics down, but what is it that makes Dario Argento the maestro? Objectively, it might be the fact that he’s made more giallo films than any other director, rounding out with a lucky number of thirteen in total. More so, it’s that he gave the genre its fundamental fashion and furnishings. His debut feature, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, takes inspiration from Bava’s format and adds extra flair and style. It was a hit, leading to the subgenre’s popularity, and it laid the groundwork for the amalgamation of films Argento would produce throughout his career.

Argento’s films are sexy. From the expected yet never unappreciated Italian fashion to the cinematography, and all the way down to the gait and exaggerated expressions of characters, swagger and seduction bleed through his films with equal profoundness to the blood. The penchant for dominant but never overbearing soundtracks — much of which are a product of his long collaboration with Goblin — perfectly accompany the highly stylized atmosphere of Argento’s baroque worldbuilding.

With a photographer and director for parents, Argento seemingly showcases that his eye for visuals is nearly inherent. Equally, he is known for the narratives he concocts, and he cites the work of Edgar Allen Poe as an early and imperative influence. With Poe’s hallucinatory and deeply cerebral horror, it more than manifests through Argento’s own crafting of concurrent dreamlike quality and intensely psychological implications on screen.

Taking his narratives from the happenings of his own nightmares, Argento bridges the gap between the fears of the public unconscious and the ua-personal recesses of his own mind, making his films wholly and horrifyingly his own. His plots are wonderfully convoluted, constantly subjecting us to guess, and guess again until we finally accept that our minds are no match against Argento’s, and our best guess is only his first twist.

Argento’s use of location is equally important to the happenings on screen, becoming essential in their symbolism as we investigate what they represent, what they permit, and how the openness of commonplace settings can be crippling. Argento’s crafting of elaborately complex plots and magnificent final set-pieces disallow “unimportant” side characters and promote the examination of numerous facets of the darkest corners of the human condition: misogyny, hatred, vengeance, trauma, and exploitation.

Dario Argento’s claim to fame, and the heyday of his career, are the giallos he released in the 1970s and 1980s. So, for this entry, I’ll be looking at the following six titles: The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Four Flies on Grey Velvet, The Cat O’ Nine Tails, Deep Red, Tenebrae, and Opera.

Onto the ranks! Spoilers ahead.

6. Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971)

On the rare occasion that we might be looking at our own mortality in the face, it’s difficult to discern whether it’ll be our actions or inactions that do us in. Equally enigmatic is whether our actions or inactions are what put us in the position in the first place.

In Four Flies on Grey Velvet, Roberto (Michael Brandon), a rock musician, is being stalked by a mysterious man and receiving odd phone calls. One night he decides to pursue the pursuer, winding up in a struggle that ends with him stabbing the stalker. Still unknown, the mysterious man’s impact doesn’t die with him, and Roberto remains entangled in a dangerous web from which he hopes to escape alive.

What’s most horrifying in Roberto’s dilemma is that there’s absolutely nothing known about anything — there’s no why to be found. The night that he accidentally murdered the stalker, someone captured photographs of the whole ordeal. They’re blackmailing him, but not for money, just for the pleasure of his suffering. His tormentor attacks him in the dead of night, taunting that they could kill Roberto then and there but won’t because they’re “not finished with [him] yet.”

As Roberto’s friends and associates begin to die off one by one, he’s the common thread and looks more suspicious each day. He has a recurring nightmare of being impaled with a stiletto and then beheaded. Each night the dream lasts longer, his anxiety pushing him further into its narrative as he feels the killer closing in. These circumstances are pressing enough to render the open world as claustrophobic, as Roberto is unable to escape the torment, even in his own home.

Parallel to this claustrophobia, Argento presents flashbacks of the killer’s past, where we see cycles of abuse and their imprisonment in a mental institution. We come to learn that this killer was committed in their youth for homicidal mania, but after the death of their father, they were inexplicably cured — indicative of who the perpetrator of their abuse must’ve been.

Answers come when we discover the killer is Roberto’s wife, Nina (Mimsey Farmer). Her father never wanted a daughter and felt cheated when he got one. So, he opted to raise Nina as a boy, abusing her constantly for being “weak.” Her father died before she could kill him, so she vowed to obtain revenge in any way she could. She states that Roberto looks like her father, so she fostered their relationship until she could enact her murder fantasy vicariously through him.

All the motives that existed in the shadows of Four Flies on Grey Velvet were thrust into the light by this discovery. The film, which began as a study of supposed bad luck turned to bad blood, then evolves into a survey of the persistence of suppressed trauma. Nina was “cured” by her father’s death, as his abuse and physical stronghold were relieved by his demise. But it’s the mental and emotional grip of his violence that persisted and plagued her.

Four Flies on Grey Velvet is searing in its implications. Roberto was an entirely innocent party. It was neither his action nor inaction that put him in Nina’s sights; rather, he was a hapless occurrence of triggering familiarity. Even if he hadn’t pursued the stalker that night and opted for passivity instead, he would’ve been targeted regardless. Through Roberto, the film sinisterly professes that sometimes we may simply be helpless to the emotional demand of others, and these by-chance sequences of events could be the ones that plague us.

5. The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970)

Engaging in murder-mysteries is fun in theory — Clue is an iconic board game! However, it’s absolutely depraved to treat death with the same sort of levity if it snakes itself into your actual reality. Exploiting death through means of either art, apathy, or personal self-interest is a behavior that reflects an attitude of its permittance, not its condemnation. Dario Argento’s directorial debut and first giallo, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage leers into the minds of individuals who host these attitudes, coming down on the topic with a bloody fist of consequence.

Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante) is an American writer in Rome. One night he passes by an art gallery, and through its glass front, witnesses the attack of a young woman. Being the key witness to an attempted murder by a suspected serial killer at large, Sam gets roped into the investigation. As he becomes more invested, though, he develops an obsession defined by nonchalance, and he starts to treat it as a game of whodunnit more than a high stakes open case.

The film’s alignment with art teases fabrication and contrivance, a form of exploitation itself. It’s discovered that one of the killer’s victims worked at an antique shop, and the last piece she sold before her death was a painting that depicted a murder scarily similar to her own. Sam tracks down the artist to find that much of his catalog consists of numerous eerie depictions of brutal killings. Additionally, the site of the crime that Sam witnessed being an art gallery is equally poignant.

We discover that the killer was the woman whom Sam had seen being “attacked,” Monica (Eva Renzi). In reality, she was the aggressor, trying to stab her husband to death. This setting of the art gallery adds to the exploitation of it all, with the windowed front inviting spectators and rendering the attack a performance. Monica was triggered by the sight of the painting, which reminded her of when she was the victim of an attack ten years prior. It drove her into a frenzy of madness, where in order to cope she identified with the attacker rather than the victim — her mind’s own way to grasp at a semblance of control.

Sam confronts Monica, trying to apprehend her himself as some sort of cop by proxy. Tracking her back to the art gallery, he ends up being pinned underneath a fallen statue — an ironic punishment as his own manipulative attitudes towards the investigation left him trapped under an art piece — before he is rescued by real cops that arrive on the scene.

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage uses the relationship between art and exploitation to investigate trauma, crime, and punishment. It muddles the boundaries between victim, perpetrator, and instigator by faulting every character involved in the narrative, showing that in all degrees of separation, permitting attitudes and exploitative behaviors regarding violence can end up promoting a cycle that also victimizes and creates its perpetrators.

4. Deep Red (1976)

As previously discussed, the giallo subgenre has a characteristic set of traits. One of the largest criticisms of Argento, and the giallo subgenre as a whole, is that it’s misogynistic. Women often fall at the pointed end of the blade with a particular intensity that we don’t always see in the murders of men. Their sexuality is somehow always connected to their characterization, whether its promiscuity, sexual insecurity, or simply just the objectifying eye of the camera. Deep Red is a standout in Argento’s filmography in the sense that it takes all of these tendencies and inverts them.

After Marcus Daly (David Hemmings) witnesses the murder of a telepathic psychic (Macha Méril), he is determined to discover who the culprit is. The only information he’s armed with is the silhouette of a figure leaving the crime scene, donned in a leather coat and gloves, but this sight of the killer was fleeting. Teaming up with a spunky reporter, Gianna Brezzi (Daria Nicolodi), they rush to uncover the killer’s identity before they close in.

Our introduction to Gianna occurs when she interrupts the boy’s club of the post-crime investigation and is met with annoyance from every man in the room. They find her unflinching confidence and career ambition an annoyance. When she and Marcus decide to team up, their dynamic is equally tense due to Marcus’ fragile male ego. He is constantly cowering in comparison to her strong posture. It’s only when she mentions that ambition is important for a woman that he shows any dominance. Popping his curved spine upright, he proclaims, “It is a fundamental fact: men are different from women. Women are…weaker,” a sentiment he clings to despite losing two rounds of arm wrestling.

Deep Red also inverts the damsel-in-distress and gallant-man relationship trope that has become commonplace across all narratives, but especially the giallo. Firstly, Marcus is not a knight-in-shining-armor in theory or in practice. He’s awkward, insecure, and dependent. Not only is this trope subverted by the fact that Marcus is unable to save the psychic from her killer, but in a role-reversal, it is Gianna who drags him out of the burning building while he’s unconscious.

The film’s opening scene is what sets the stage for both the tone and conclusion of Deep Red. Taking place within a house at Christmastime, two shadows engage in a struggle, resulting in the stabbing death of one. The knife falls at a child’s feet. With frilly socks and heeled black shoes, our expectations tell us that the child is a young girl, but it’s actually Marcus’ friend, Carlo (Gabriele Lavia), instead. This flashback to Carlo’s childhood shows the crime that the murderer is now killing again in order to cover up. The murderer is revealed to be Carlo’s mother, Martha (Clara Calamai), supplementing the female-centric narrative of Deep Red.

Deep Red isn’t the only giallo, or even Argento giallo, to center on a female killer, but it is a standout in the bunch of films that mostly center on strong, valiant, lustful men who punish the women in their lives, use them as tools to accomplish their goals, and endanger them for their own ambition.

It’s still far from a feminist film, as it settles into the romanticism of having Gianna and Marcus fall in love despite his sexist beliefs that bluntly misalign with her own attitudes. Still, though, it comes across as an intentional subversion of expectation that adds an additional layer to Argento’s arguably most cherished film, even functioning as some semblance of a foil to his later film, Tenebrae — but more on that later.

2. Cat O’ Nine Tails (1971)

The greatest mystery of humanity might be that we will never fully understand how our brains work. Consequently, we’ll never precisely know the mechanics of empathy; it’s the root of the nature-versus-nurture debate. But when we find out that someone has committed a horrible violent crime and justified it by claiming decreased relation to people or citing childhood trauma, we still don’t accept it as a reason because they’re not the only one. Plenty of people have minds like theirs or histories like theirs but don’t go on to harm others. This debate of psychology has no end in sight, and it’s what lays the foundation for Cat O’ Nine Tails.

After a medical complex is robbed, a killer is on the loose. “Cookie” (Karl Malden), a blind man and retired journalist, overhears discussion of blackmail and rushes to the scene. Teaming up with an investigative reporter, Carlo (James Franciscus), the duo rushes to uncover who the killer is and what secrets lie within the documentation he stole.

The objective of the medical complex is left as a mystery for much of the movie. Everything is top-secret and all employees are hard-pressed to utter even a single hint towards what goal the scientists were working to discover, adding suspicion to why everything was so tightly under wraps. The only semblance of a clue is the “GENETICS” folder that we see in passing, but knowing the complex has a focus on fertility, genetics, and heredity, it still doesn’t provide us with much.

We come to find that the complex is investigating “criminal chromosomal patterns,” positing that those possessing XYY have tendencies towards criminality. Parallel to this discovery, the scientists were working on a drug that could alter one’s genes away from the pattern. One of the lead researchers, a medical prodigy, Dr. Casoni (Aldo Regianni), is revealed to be the thief and killer. After discovering he has the XYY pattern, he knew he’d lose his entire career if found out. So, he stole the documentation of proof and murdered Dr. Calabresi (Carlo Alighiero), the individual threatening to blackmail him by exposing his test results.

This operation all calls to mind the commodification of healthcare, and hyperbolically, in this case, emotions. In the case of blackmail, Dr. Calabresi was prioritizing his own financial gain over the benefit of the people, making him a figure of medical corruption. In an exaggerated manner, of course, this could come to represent medical discrimination against individuals with mental illness and pre-existing conditions.

Despite the fact that Dr. Casoni actually ended up acting criminally, in both theft and murder, it’s unclear whether it was his genes that led him to it or the desperation for financial security that put him at threat by a larger institution’s exploitation of his medical history. Cat O’ Nine Tails is complex in its investigation of the origins of aberrant psychology. Showing that even when there’s an explicit seed of corrupted nature to be found in the mind, the answer to our brain’s mechanics will forever be an enigma to the inevitable influences of nurture.

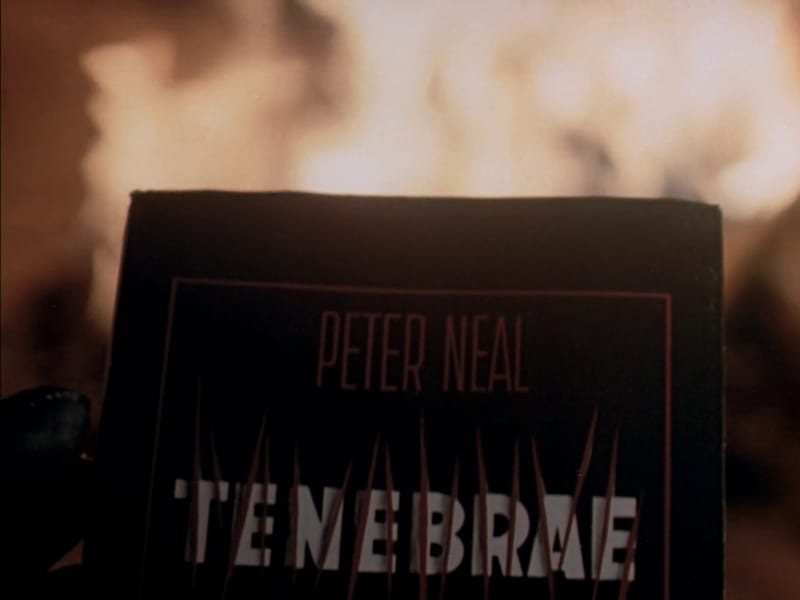

2. Tenebrae (1982)

Murder is an industry. Hitmen and assassins are the more explicit businessmen, but horror films, murder-mystery novels, true crime podcasts, and the like are equal contributions to the corporation of carnage. In many ways it’s exploitation. How does this constant absorption and oversaturation of brutal media seep into the everyday occurrences we may encounter? When and how can media become murder? Tenebrae examines this with a mix of narcissism, blood, and hypocrisy.

Writer Peter Neal (Anthony Franciosa) is in Rome to promote his newest murder-mystery novel, also titled “Tenebrae.” Upon his arrival, he discovers that someone has begun a killing spree in honor of his book. As he, his assistant, Anne (Daria Nicolodi), and the police investigate the who and the why, they inch incredibly close to motivations with implications that reflect on more than just the killer.

Given the meta nature of Peter’s book being identical to the title of Argento’s film, these two pieces of work are inseparable. The novel is self-described as being about “human perversion and its effects on society.” Therefore, so is the film.

Peter Neal is immediately posited as an icon, a dangerous symbol in the eyes of the unhinged. This intersection of morality and media is what drives the film forward: the killer feels justified by the pages in the book, and inversely, a critic calls the book “sexist” for its brutal violence towards women. Tilde (Mirella D’Angelo), the aforementioned critic, and her lover, Marion (Mirella Banti), are brutally murdered by the killer because of their “perversion.” The killer leaves a note stating, “So passes the glory of lesbos,” an act of homophobic violence that seemingly only serves as proof of Tilde’s criticism of the book’s misogyny.

Later on, Jane (Veronica Lario), Peter’s fianceé, is revealed to be having a love affair with his friend, Bullmer (John Saxon). Her death is the most tortuous and violent of all. Although her killer is revealed to be an obsessed TV book reviewer, we come to realize that not only did Peter kill him but that Peter continued to kill in order to punish Jane and Bullmer and to make it appear that the killer was still at large. His own violence was rooted in his novel’s promotion, keeping him at the center of everyone’s radar, and incredibly hypocritical and misogynistic, given that he also was having an affair.

Throughout the film, there are peeks into the history of an unknown man — who is uncovered to be Peter himself — where we see flashbacks from his adolescence in which he murders a woman who had previously humiliated him. With this added knowledge, the metafiction of Tenebrae becomes abundantly clear. Within his novel, Peter implemented subconscious misogyny that he claimed was never there. With this implicit bias in the writing of the book “Tenebrae,” the blatant bias of Tenebrae is unveiled. Yet the daunting question still remains in grey: if not for writing the book in the first place, is Peter now responsible for the murders he inspired simply because we know his stake in it all is close to home? Was the book “Tenebrae” a subconscious calling card to like-minded misogynistic maniacs, and by extension, what does that say, if anything at all, about the film Tenebrae and its creator?

1. Opera (1987)

Performance is exalting and terrifying in its vulnerability. As a performer, your role is to serve the audience — to exist for their entertainment and judgment. In any production, it is both essential and inevitable that every person involved is being watched, and therefore, is simultaneously watching. It’s this exchange of perception that rules Opera. The film is laden with imagery of eyes, lenses, and POV shots that profess the importance of vision and its implications.

Opera follows the story of a young understudy turned prima donna, Betty (Cristina Marsillach), who is being pursued by a stalker in a vicious cycle of catch-and-release as she is repeatedly bound and subject to a line of pins underneath her eyes that force her to watch him murder those around her. In her shows, the music is operatic; in the killer’s act, the music is metal — each a juxtaposing genre of performance in their own right. This relationship results in a transference of exhibitionism: though where Betty was freely and openly a performer, she is now a forced voyeur to the horrific recital of her captor. It’s not only an exchange of the watcher and the watched but a swap of power.

Forbidden sights are viewed through bars: the line of pins beneath Betty’s eyes and the grate of the air vent in her apartment as the child spies on her from within the duct. There’s a reminder of the corruption and lack of consent, but powerlessness in knowing there isn’t a way to stop it. Inversely, Opera also uses the robbery of sight as punishment. Betty’s friend, Mira (Daria Nicolodi), has her vision, and life, taken when she’s shot through a peephole, the bullet entering through her eye. She’s murdered because she’s seen as interference, obtrusive to the killer’s fantasy. Later on, in an ironic spin, the stalker has his own eye gouged out by a raven, a vengeful form of poetic justice.

Betty’s sexuality runs through the narrative’s subplot. We see her engage sexually, but she admits, “She’s a disaster in bed.” But she doesn’t know why and claims only that sex “has never worked” for her. With her being a victim to the killer’s overt sadomasochistic displays, she is constantly at the liberty of men’s sexual wiles and objectifying eyes. It is only in her reclamation of the power of gaze that Betty overcomes.

Amidst being at the center of sporadic endangerment, Betty only feels safe at the opera: the sole place in which she is willing and in control of how she is perceived. She eventually uses the opera, and her own performance, as a tool to capture her tormentor on her own terms, knowing the sight of her exhibitionism is irresistible to him. Through this, Betty obtains sexual control in the cyclical push and pull of sadomasochism spurred by her attacker. With this she also gained the confidence and agency she had struggled to obtain, removing herself from the chauvinistic male sight and claiming the power as her own.

The giallo subgenre, spearheaded by the master, Dario Argento, has had a massive influence on the horror genre at large. His elegant balance of extraordinary style that doesn’t detract from the substance is what’s laid his claim in the hearts of horror lovers. Within the industry itself, from masked killers, implicating POV shots, iconic musical accompaniment, and inventive avenues of slaying the unsuspected, it’s easy to eye the direct inspirations from his work in perhaps the most coveted era of horror: the late ’70s-early ’80s slashers.

Yet Argento’s work stands alone, embodying a subgenre of dramatically unique filmmaking with narratives and images that stubbornly stick in your skull. He dissects the darkness of past trauma, personal agency, and revenge with a delectable combination of sexiness and savagery, leaving a lasting impression long after the credits roll. It’s why we watch his films, why we return to them, and why his name is forever synonymous with the image of giallo.