Washington, D.C., and the Quest for a Perfectly Square City

If you ask a regular person to draw a city, not based on an existing city, but rather the concept of “city,” they might start by drawing the borders. To draw those borders, they might begin by doing something that almost no actual cities have done—make it some kind of simple shape. A square, or a circle, or a rectangle, something like that. Then they’d fill in the city stuff—streets and buildings and parks—within that shape.

This isn’t the way cities really look, of course. The borders of many cities depend on water in some way. There are cities made up of one or more islands, such as New York (apologies to the Bronx, the only part of the city on the mainland), Hong Kong, and Singapore. Many are structured on coasts, such as Los Angeles, Chicago, and Shanghai. Still others are constructed around rivers: Pittsburgh, Paris, Cairo. These natural features are all irregular. Most older cities have, through centuries of many small decisions by many different people, expanded and contracted until they become sort of blob-shaped. Cities are like fungi, growing in ways that make internal sense but not necessarily geometric sense as a whole. They aren’t triangles, circles, or rectangles. That would be weird.

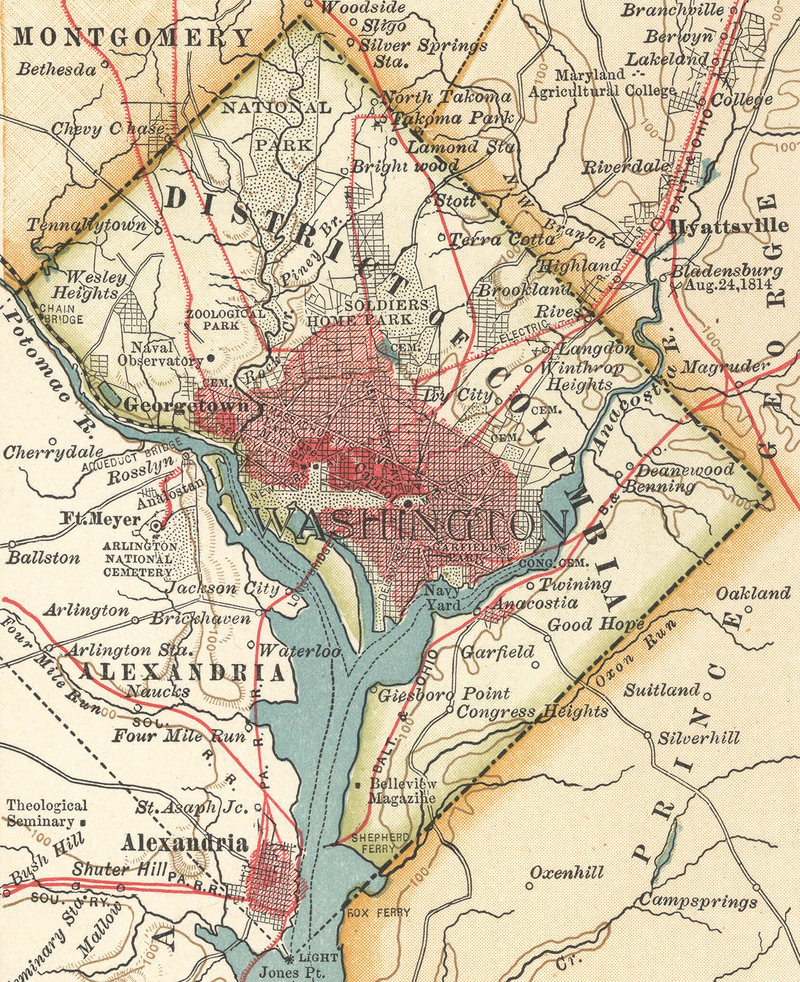

Washington, D.C., though, is about as close to that square drawing as any real city gets. It was drawn as a perfect square, with unnervingly straight lines passing at unnatural angles through hills, waterways, and properties. Even stranger, it remains that way today, more than 200 years later—with the notable problem that the city gave away about a third of its land to some angry neighbors. “Of all the planned cities in the world, Washington is probably closer to the original plans than any other,” says Don Hawkins, an architect, historian, and expert on the history of the U.S. capital. But even today, if you look at a map of most cities and then you look at Washington, you think: Wait, does it really have three straight lines, at 90 degree angles, as borders? What the hell?

From the first meeting of the Continental Congress, in 1774, until 1800, the United States did not have a capital city. It had a series of places where Congress met, including Philadelphia and New York, which are fairly well known as early “capitals,” along with a series of random towns that served as temporary capitals for as little as a single day (see Lancaster, Pennsylvania). This was always treated as a temporary situation. The Constitution includes some extremely vague and minimal instructions for the creation of a permanent capital city. Those instructions are: It will actually be a District (which contains the city), be no larger than 10 miles square (meaning, 100 square miles), and be carved from land ceded by one or more states.

Philadelphia and New York were viewed as unsuitable for this purpose because, in the absence of long-range communication and efficient transportation, it would be a massive advantage for anyone to have the seat of federal power in their own hometown. That city would become incredibly powerful and probably corrupt, and the people of that state would have undue influence over the governance of the country. The writers of the Constitution went far in the other direction, and decided to create a new city (district) out of whole cloth, in which, effectively, its citizens would exchange congressional representation for this valuable proximity to federal power.

On July 16, 1790, Washington signed the Residence Act into law, which specified the location of the new capital, though not exactly where it would be, just that it would be on the Potomac, between the Anacostia River and Conococheague Creek. The location, as Hamilton fans well know, was also a compromise, bordering on a bribe, to Southern states who were annoyed at having to take on the burden of paying down the debts of Northern states from the Revolutionary War. Placing the capital city in the South, or at least what was then the South, was a concession to get those states on board.

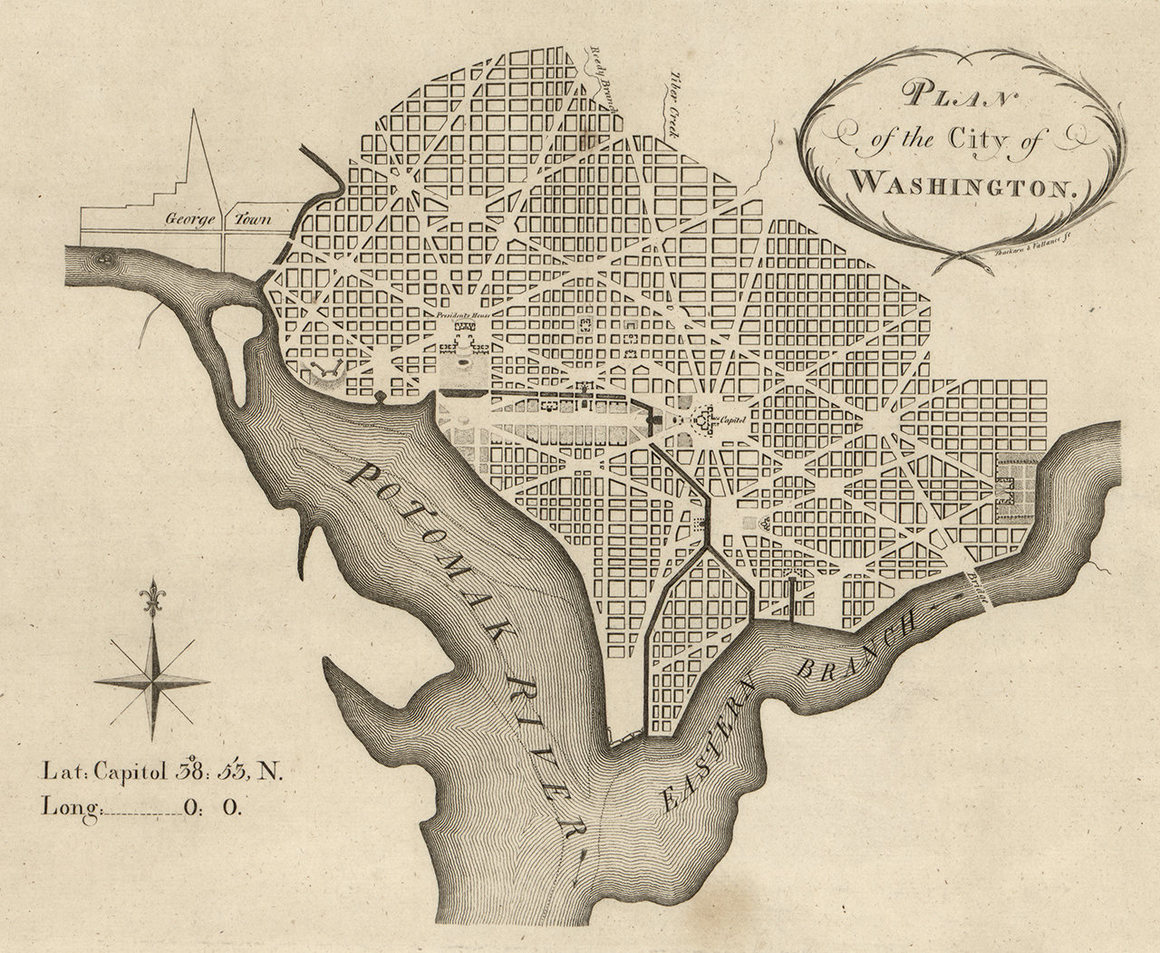

From there, Washington and Jefferson worked together to figure out exactly where the capital should be. The planners—the biggest influences were Washington, Jefferson, and the sole first planner, Peter L’Enfant—went incredibly literal with the Constitution’s guidelines. Ten miles square? Fine. Make a freaking square that’s 10 miles on each side.

But the shapes of the waterways listed in the Residence Act actually ended in a point, so they rotated the square, with a corner facing down to meet at the juncture of the Potomac and the Anacostia.

The site included the two towns—settlements, really—in the area: Georgetown and Alexandria. But the district spanned the Potomac, which was (and is) the border between two states, Maryland and Virginia. Both gifted a chunk of land to be the new District of Columbia. And so it would be a perfect square with a river running through the middle. At least for a little bit.

Washington and Jefferson had hired Pierre L’Enfant, who went by Peter, to plan the new capital. L’Enfant had worked on Manhattan’s Federal Hall, and was deeply tied to influential early Americans, including Washington and Alexander Hamilton. It is very important to note that in these early decades of the country, it was a very small number of men building this thing from scratch, only barely knowing what they were doing and making huge decisions that would affect the country forever. Speed was also incredibly important. This country needed to be up and running, because it was seen as fragile and liable to splinter at any moment. “The President and Congress were inventing everything as they went along,” says Jane Levey, a historian at the Historical Society of Washington, D.C.

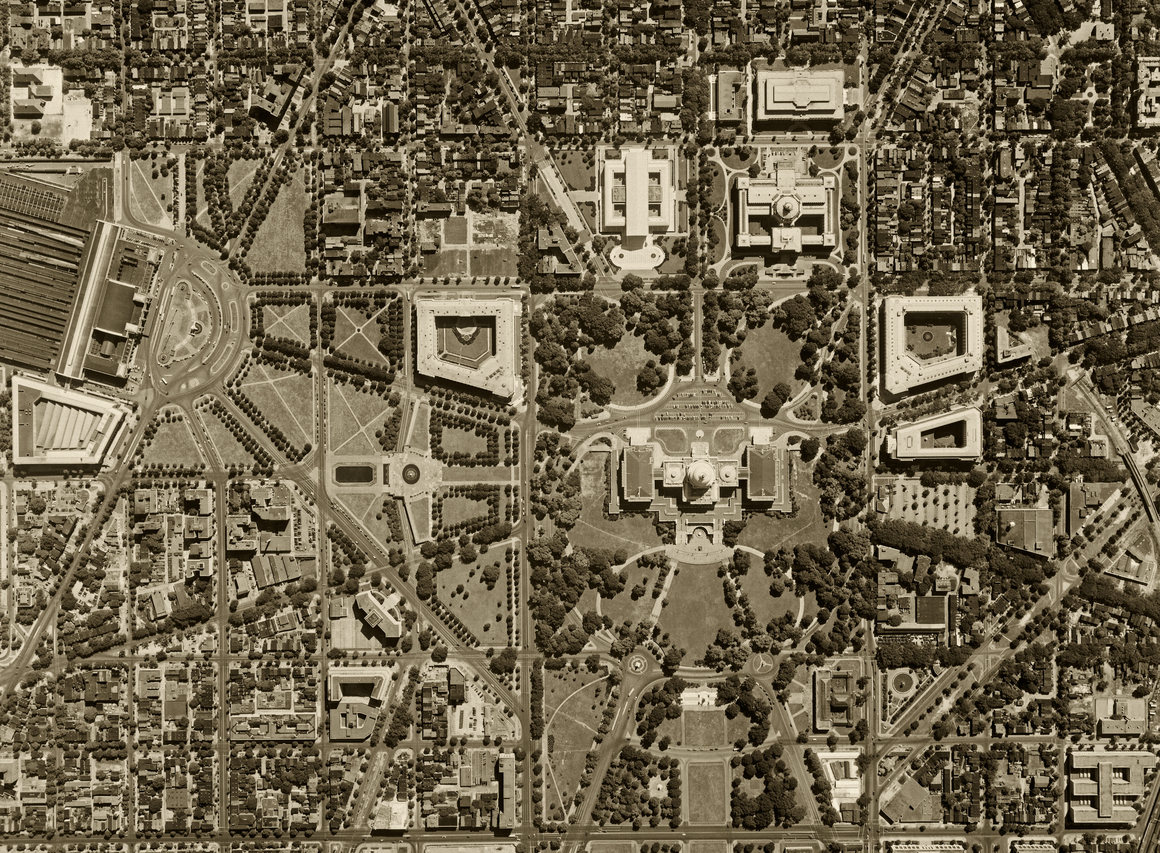

In this environment, and with the federal government nowhere near the size it would soon become, L’Enfant’s task was seen as important, but by no means the most or only important thing being created at the time. So he basically had free reign to design an entire capital city by himself. He created a symbolic layout, with three groups—the legislative and executive powers, plus “commerce,” which was supposed to represent the people—having their own centers, with streets radiating out from them. His borders were incredibly simple, but his street planning was artistic and complex. It’s not just a grid. It’s a grid overlaid with geometric shapes. “Until the 19th century, nobody had ever thought of a city in terms that were too complex to draw on your thumbnail,” says Hawkins. “And L’Enfant was the last guy who could do it without having to consider the complexities of the Industrial Revolution.”

All of this, though, was built in just one section of the District of Columbia—the Maryland side, near the meeting of the rivers. Today, “Washington” and “District of Columbia” are synonymous, but they weren’t always. L’Enfant’s plan saw Washington as just one town, along with Georgetown and Alexandria, as well as a hefty amount of open space for farmland, within the District. Washington would eventually swallow Georgetown and expand all the way to its square borders—making Washington and the District of Columbia the same thing.

Eventually, the city became a harbinger of the Civil War. “This was a city controlled by Congress,” says Levey. “No other city in the United States can be said to be under exclusively federal control.” Abolitionists found the District a useful stepping stone. They agitated heavily for the end of slavery within its square borders, and by 1840 this seemed an inevitability. This annoyed Virginia deeply because Alexandria, which was part of the District, was a major trading center for enslaved people. On top of that, the part of D.C. that was gifted by Virginia had not seen much prosperity from being included in the District because all of the important buildings were placed on the Maryland side. So Virginia essentially reneged on the agreement, and asked the government to give them back their land. The government, dealing with an impending Civil War and not really concerned very much about the backwater, across-the-river section of D.C., acquiesced.

There have been scattered efforts to put the Virginia back in D.C., to make the square capital square again, but none have succeeded (or really gotten anywhere near succeeding).

Washington, D.C., is not the only major planned city in the world. It’s not even the only planned capital city. But none of the others have borders quite so rigid. The only ones close to Washington’s regularity are Brasilia, which is shaped like an airplane, and La Plata, the capital of Buenos Aires Province in Argentina, which actually is a square.

That Washington’s borders were initially drawn as straight lines is very much in keeping with the way the vast new territory of North America was divided by European powers. Surveying was expensive and time-consuming. It was generally reserved for rivers and coastlines, which settlers needed to chart for transportation purposes. Beyond those, they’d generally just start at a point along a waterway and draw a straight line, and deal with any complications later. That’s why so many American states have straight lines, or something close to them, as borders, as do many countries in Africa—another case of European laziness during the Scramble for Africa.

None of this is so strange. Most of the states and cities in the United States without some kind of hard natural border (like a river or ocean) were mapped out this way, at first. “It makes sense because you’re essentially selling real estate if you’re building a town,” says Hawkins. But slowly they would expand, devour neighboring towns, cross rivers, and grow—and things get more convoluted.

Washington could never do this, for a couple of reasons. Initially, the Constitution mandated that the District could be no larger than 100 square miles. But by the Civil War, D.C. was actually quite a bit smaller than that, having given back about a third of its land to Virginia. Today, D.C. is only 68.34 square miles. Constitutionally, it absolutely could expand.

There doesn’t seem to be much demand from anyone in Virginia or Maryland who is not already a part of the District to become a part of the District. “If anything, people want to get out of the District,” says Hawkins. Many, though not all, of the towns surrounding D.C. are very wealthy, providing a great deal of tax revenue to their respective states—revenue those states would lose if those towns became a part of Washington. There’s also the issue of voting rights, in terms of representation in Congress; those in Maryland and Virginia would not be excited to give them up to live in Washington, putting aside for the moment of the idea to make D.C. a state of its own, with two senators. The District is so unpopular, in fact, that far from expanding, as normal cities often do, there’s been more movement on making it even smaller. One recurring proposal would find most of the District moved into Maryland, which would restore representation to its residents. (Though only 28 percent of Marylanders support that annexation, according to a 2016 poll.)

So Washington, D.C., stays as it is, with two right angles and three straight lines. That’s only partly the way it was planned, but that’s the way it will be.