The Unsettled Legacy of the Bloodiest Election in American History

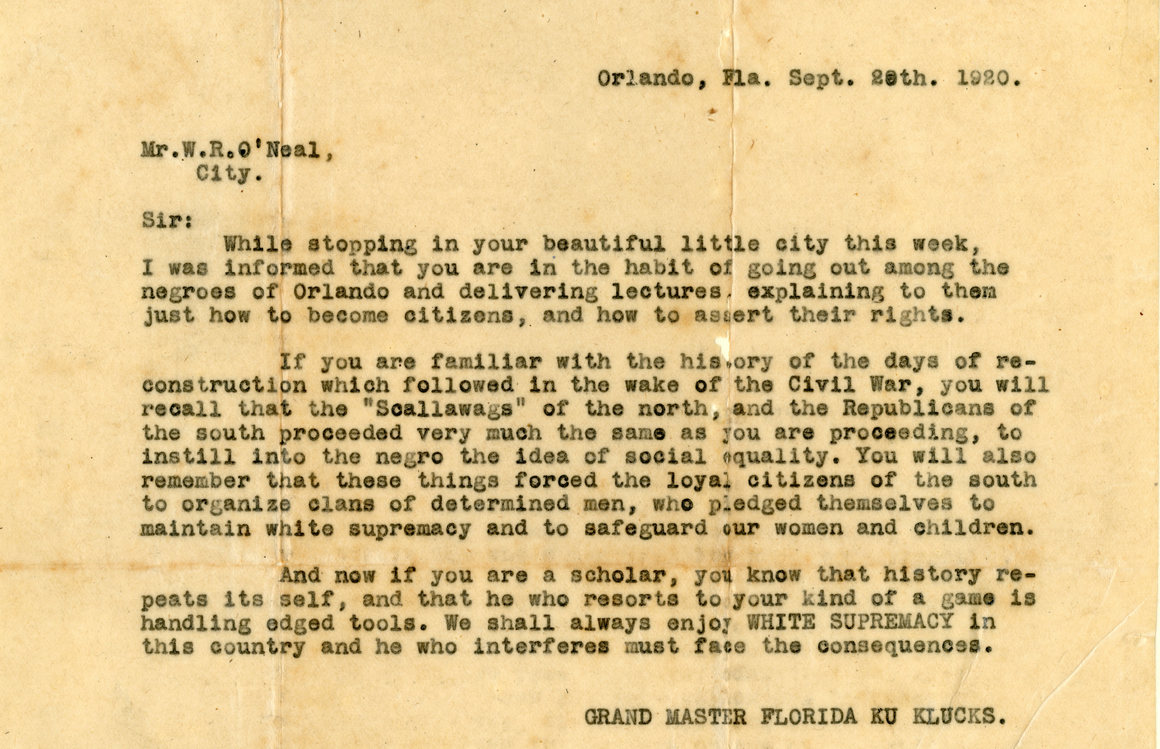

On November 2, 1920—Election Day, 100 years ago—Moses Norman of Ocoee, Florida, joined more than 25 million Americans in going to the polls to cast his vote. Unlike most of those other voters, however, Norman was Black, and exercising his rights meant putting his safety at serious risk. Just days earlier, the Ku Klux Klan had rode through nearby Orlando, trying to send a message to Black people who planned on voting. So it came as no surprise when Norman was turned away on Election Day, Fifteenth Amendment be damned. No one knows, in detail, precisely what happened next. But for all the differences in accounts, the following is clear: This simple act of self-assertion led to the murders of at least four Black people, and the story was largely kept under wraps for decades.

A new exhibit, at Orlando’s Orange County Regional History Center, aims to correct that historical omission. Called Yesterday, This Was Home: The Ocoee Massacre of 1920, the exhibit draws on oral histories and a range of primary materials to explore the events of that day, as well as the history that led up to and followed it. It’s also concerned with something subtler, and perhaps even more challenging: the difficulties of piecing together a narrative that was quite literally and deliberately torn apart, of illustrating lives that had been forcibly erased from most records. The exhibit, which is open for socially distanced in-person visits, launched in October 2020 and will close in February 2021.

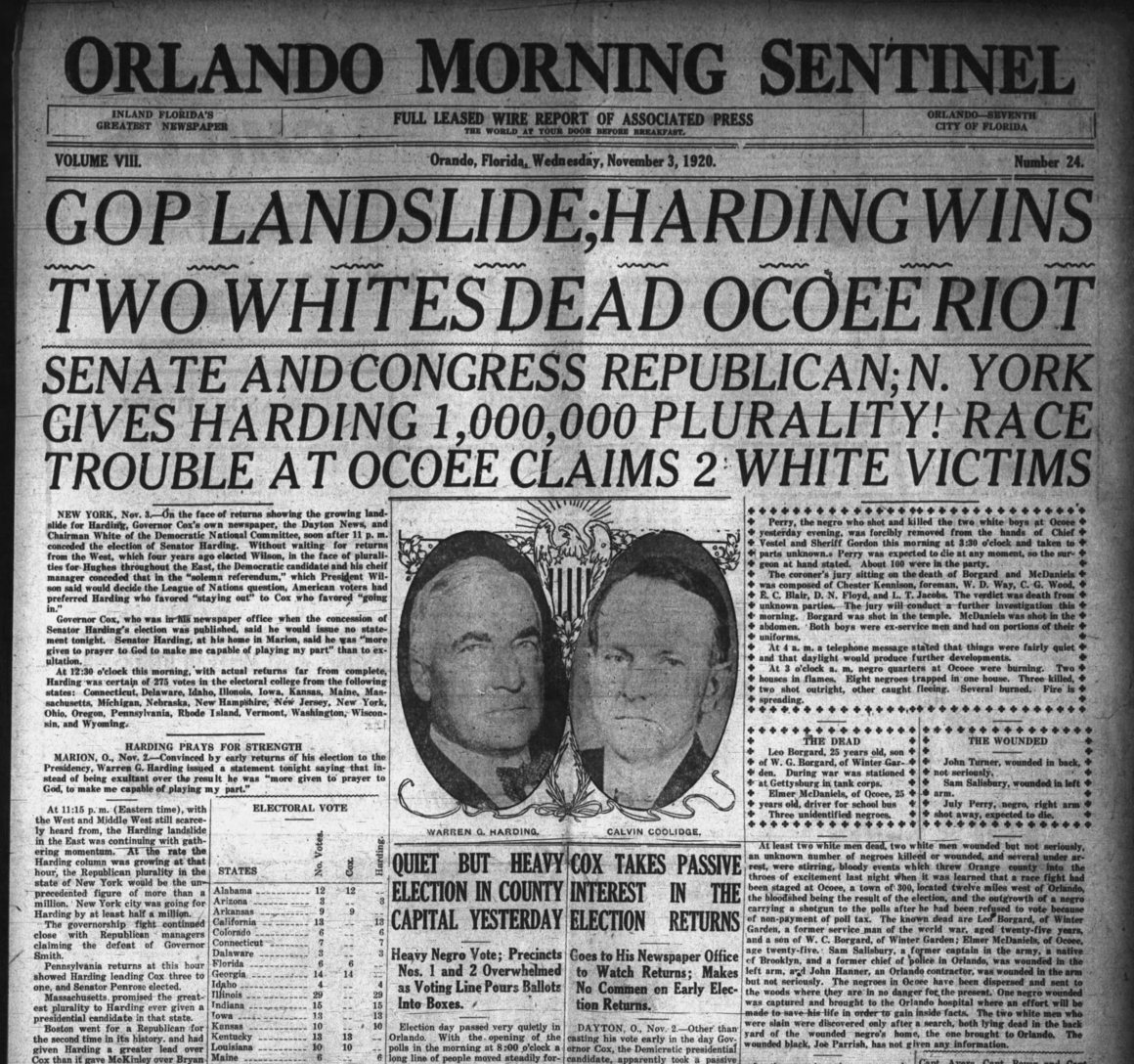

Pamela Schwartz, the History Center’s Chief Curator, says the available documents confirm that the massacre killed four Black people (though some estimates speculate it could have been in the dozens). Only one of those four casualties, moreover, is known by name: July Perry. After Moses Norman attempted to vote, local white mobs took his friend Perry to jail, then returned hours later to lynch Perry. (Norman survived and later moved to New York.) All day long, meanwhile, mobs unleashed acts of racist terrorism against Ocoee’s Black community en masse, burning people’s homes and other buildings throughout the town’s Black neighborhoods. The remains of three other people were found in the ash of one of these buildings, and recorded clinically in an invoice from the worker who removed the bodies. That was more mention than the Black victims received from the Orlando Morning Sentinel. The next day, the paper ran the headline: “GOP Landslide; Harding Wins; Two Whites Dead Ocoee Riot.” Within the next few years, virtually all Black people had left the town.

That invoice and headline illustrate the challenge facing Schwartz and other researchers. They’re typical of what she calls the “intentional obfuscation” of much of Black history, the product of official records that are sketchy or apathetic or worse. As a result, much of the evidence we inherit of such events is indirect and incidental. “You just didn’t go to Ocoee,” recalled Francina Boykin, a Black woman from nearby Apopka, while describing her childhood in an oral history that informed the exhibition. “You just didn’t.” People don’t always know why they were raised to avoid the town, but Boykin’s comments echo “the sentiment from almost every Black person we’ve done an oral history with, [even on subjects] totally unrelated to the Ocoee Massacre,” Schwartz says. That’s the thing about oral history, she adds. It leads to “this whole other world of information that lives in each individual”—information that is not always precise, but is nevertheless revealing.

It is revealing, of course, from all angles. White oral histories have also made major contributions to the study of the Ocoee Massacre, thanks largely to the work of Walter White. White, who was Black and who worked for the NAACP, went to Ocoee in the 1920s to investigate—passing as a white man interested in buying property in the town. Ocoee’s white residents freely boasted to him of their families’ roles in the massacre, with some claiming to have killed more than a dozen Black people. Such numbers seem unlikely, Schwartz says, but the claims say much about the attitudes that led to the massacre in the first place.

Those attitudes continued to haunt Ocoee and neighboring towns for decades. In the 1970s, as Black people began to trickle back into the community, a man named Fred Wilson quickly left after burning crosses started appearing on his lawn. Timothy James, whose family moved to Ocoee in the 1970s, told Schwartz that it was “like sticking his finger in an electrical socket.” As late as the 1990s, one Black man reported feeling unable to continue in a new job he had just started in town. There was something about the environment, he told friends, that just felt unsafe. In the early 2000s, Schwartz says, the History Center declined a request to do an exhibit on the massacre, fearful that the subject was too politically provocative.

Today, Ocoee is taking some steps to shed light on this history, and to reach out to the town’s Black diaspora. John Peterson, a minister whose great-grandparents lived in Ocoee during the massacre, visited the town for the first time in November 2020, for an official apology ceremony tied to the centennial. Ever since he was a little boy in Fort Lauderdale, he says, the image of July Perry’s dead body “was vivid in my mind,” just from the stories his grandparents had told him. He was scared to enter the town, he says, but is ultimately glad he did, and pleased with some of the progress he observed.

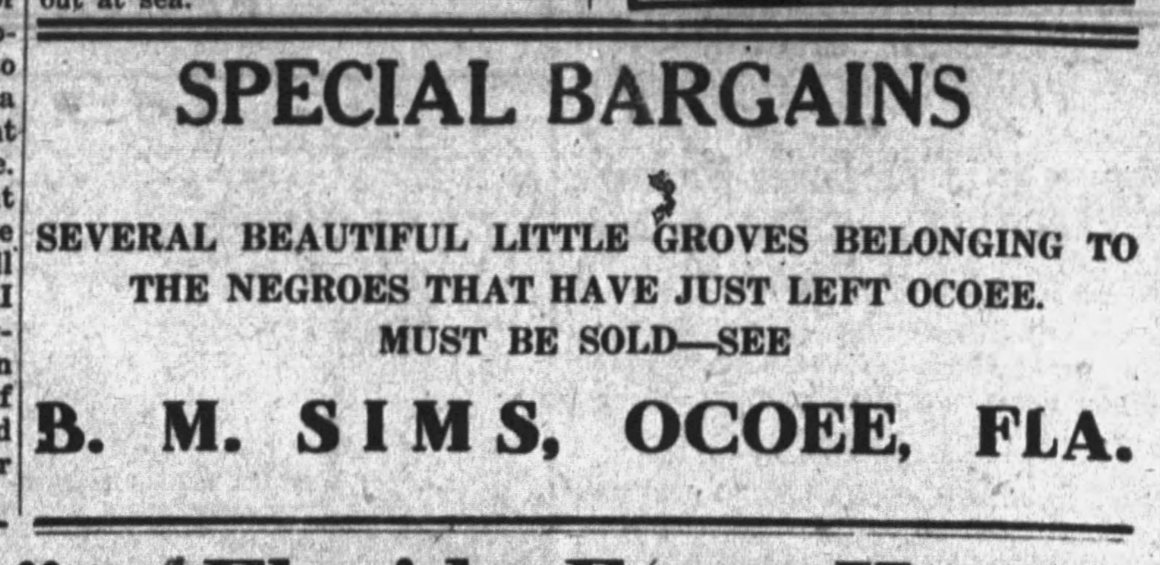

That said, even if hearts and minds have changed to some extent, Ocoee is still haunted by another aspect of the massacre’s legacy: its contribution to the generational racial wealth gap. Peterson’s great-grandfather, Valentine Hightower, sold more than 50 acres of Ocoee land in 1926 for $10 (about $147, adjusted for inflation). Today, Peterson says, it’s developed property that includes two baseball diamonds. His family, like so many others, never saw returns on their investments in the community.

“Something has to be done,” Peterson says. He’s not sure exactly what, and simply telling the town’s story was a hard enough first step. “Tulsa is well-known because people started talking about it,” says Schwartz, referring to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. At long last, after 100 years, it seems like the silence might be breaking in Ocoee.