California Is Named for a Griffin-Riding Black Warrior Queen

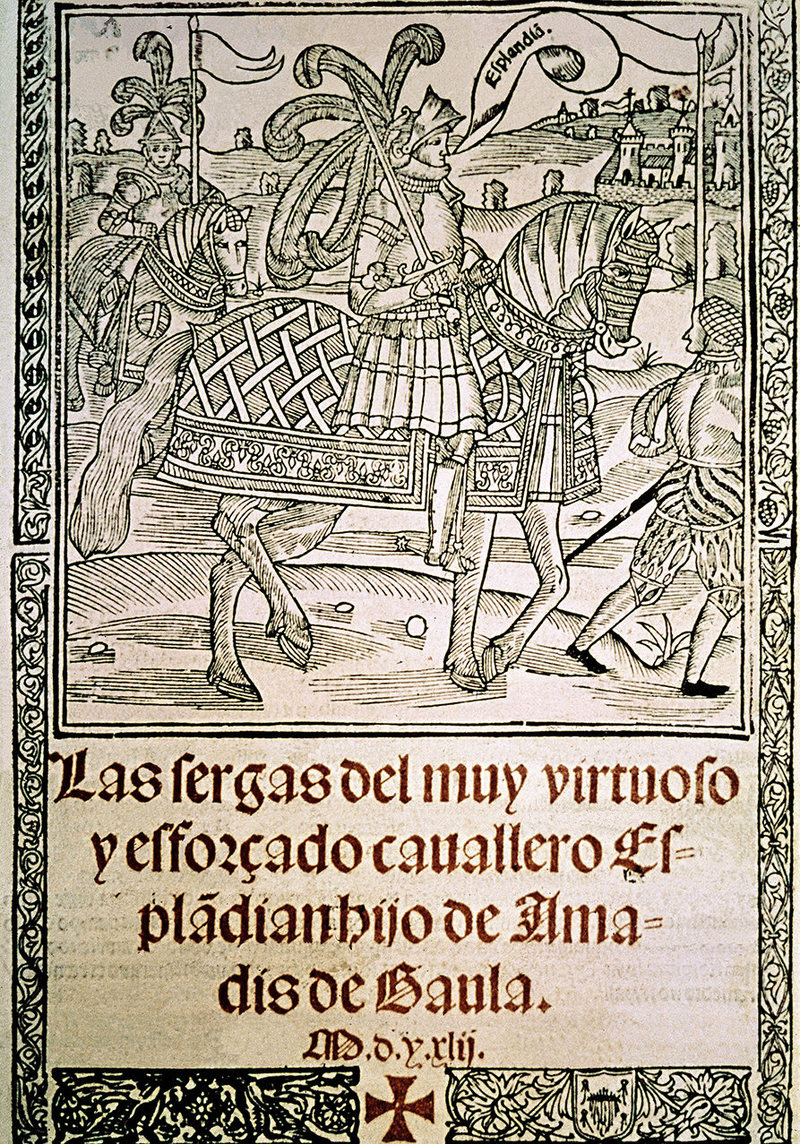

California has long been associated with fantasy, but few people know that centuries before Hollywood, it drew its very name from an imaginary kingdom—one ruled by a Black queen. Around 1530, when Hernán Cortés’s conquistadors, amid shipwrecks, mutinies, and the destruction of the Aztec Empire, arrived at the peninsula on Mexico’s western side, they christened it “California,” after a fictional island in a Spanish book published decades earlier. The name, later extended from the peninsula (now Baja California) to the mainland coast to the north, endured, surviving the region’s incorporation into the United States in 1850. Meanwhile, the novel of chivalry that spawned it, Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo’s Las Sergas de Esplandían, has been all but forgotten (despite being memorably cited by Cervantes as one of the books that turned poor Don Quixote’s brains to mush). Yet its portrait of California’s queen, the dark-skinned warrior Calafia, is worth revisiting—not just for its marvelous details, but for the light it sheds on medieval European attitudes about race.

At least initially, Queen Calafia seems like she could have sprung from the pages of a modern fantasy novel, ruling a kingdom that wouldn’t have been out of place in Westeros or Middle Earth. Her island, located “on the right side of the Indies, very close to … the Terrestrial Paradise,” is filled with gold and inhabited only by Black women, who tame wild griffins to ride into battle (fed with the flesh of any unfortunate men who show up). Calafia herself is described as beautiful, strong, and courageous. The book portrays her in an unfailingly positive light, though it ultimately places her under the control of medieval European patriarchy.

While it might seem startling today to find such a figure at a time when Europe was just emerging from the Middle Ages, scholars who specialize in race during the period offer intriguing insights into what a character such as Calafia would have meant. Cord J. Whitaker of Wellesley College, who studies medieval notions of race and their modern legacy, explains that medieval Europeans lacked “a hard and fast set of hierarchies related to skin color.” This was mainly because “before the Reformation, Catholic Christianity was hegemonic,” with the idea, inherited from the Crusades, that the religion was destined to spread to all corners of the Earth. “If your number one concern is converting people all over the world,” Whitaker says, “you have to be accepting that anyone who looks any way could be holy.”

In fact, the patron saint of the Holy Roman Empire, St. Maurice, was Black, and consistently represented with African features from the mid-13th century on. “At the same time,” Whitaker acknowledges, “sometimes you do see dark skin associated with evil and demons, but these more negative attitudes were held in check by the church’s need to be global and enfold people who look all kinds of ways.” This changed with the fragmentation of Christianity during the Reformation and the rise of nation-states and colonialism, including plantation slavery. “Money and wealth … ultimately became the first concern, over and above conversion,” Whitaker adds, opening an era in which black skin “increasingly signaled ‘enslaveability’ and the making of capital.”

Erin Rowe of Johns Hopkins University, whose newest book traces the history of Black saints in early modern Catholicism, takes a slightly more tempered approach to medieval views on race, arguing that “overall, black skin was equated with ugliness, barbarity, and paganism,” and that in the medieval Mediterranean slave trade, which trafficked in a range of peoples, “white skin was prized over all.” Rowe says that while there were “anti-Black discourses” in 16th-century Spain, where there were a limited number of Black enslaved people and freedmen, they didn’t focus on ideas of “entrenched and inheritable bodily difference,” like the idea of African biological inferiority that white Christian slave owners would later invent to justify their inhumane treatment of the Black people they enslaved. (According to Rowe, such notions of biological inferiority existed at the time but were mainly reserved for Jews, including former Jews who had converted to Christianity.)

Rowe thinks readers of the period would have seen Calafia’s skin color as “neither inherently positive nor inherently negative,” but primarily as “exotic,” which, of course, is problematic in its own right. She sees the queen’s Blackness as “bound up in her femininity and her otherness,” noting that Calafia, as a “Black Amazon,” would have provoked both “wonder” and “disgust.” She also points out that in the early modern era, female warriors like Calafia were usually associated with “a negative vision of disrule, or monstrosity … or what happens outside of ‘civilization.’”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, Calafia does not long remain outside of Christian civilization or its patriarchy in the narrative. She and her female troops, hungry for glory, join a Muslim army besieging Constantinople, which, in a bit of wishful alt-history, is still in Christian hands (in reality, the city had fallen to the Turks in 1453). The rest of her story, which sees Calafia’s defeat, followed by her marriage to a Christian warrior and conversion to Christianity, is a disappointing denouement for today’s readers—but explains the book’s approach to her.

Whitaker places Calafia’s story within the medieval genre of “Crusades romances,” which tend to involve “a dark-skinned Muslim or pagan who is defeated by Christian forces” and is then converted. In some versions, the conversion is even accompanied by a miracle at once religiously symbolic and racially charged: The new Christian’s skin turns “beautifully white.” But others Crusades romances feature new Christians, especially women, who remain Black and are recognized as beautiful, because, as Whitaker says, at the time, “you need these beautiful Black Christian women to have a global church.”

Rowe agrees, noting that Calafia’s conversion would have fed into “millenarian ideas about the domination of Christianity,” according to which the entire world would be converted prior to Christ’s return and the Last Judgment. Ultimately, she says, religion still tended to trump race in the 16th century: “Christianity was viewed as a sign of being civilized, and therefore signaled reason and sophistication.”

At least before Calafia’s defeat and conversion, it’s tempting to see her as a symbol of Black (or Indigenous) power, or of feminist leadership. A few writers have also embraced her as a lesbian figurehead. There is a certain satisfaction in freeing the character from the limitations of her original story—penned by a Christian European male—but there may be as much or more value in trying to understand her complex place in the history of Western ideas about race.

Whitaker, who also studies medievalism—the use and abuse of ideas about the medieval past—points out that what he calls “white supremacist medievalism” was on “full display” during the 2017 Charlottesville protests. White supremacists tend to look back with nostalgia on the Crusades, which are bound up with the fantasy of a purely European medieval past. Calafia’s story, which was widely read in its day, punctures that fantasy by revealing a certain degree of tolerance—and intermarriage—even as it underscores the misogyny and religious chauvinism deeply rooted in European heritage.

And a year in which Americans are engaged in painful discussions about Black lives, the history of race, and the meaning of symbols seems exactly the right time to rescue that story from obscurity and examine the complex legacy of California’s name.