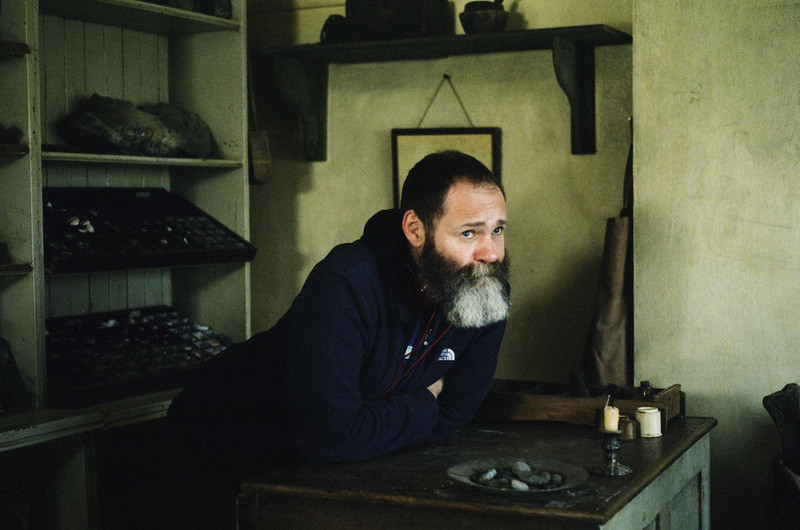

Love, Labor, and Human Heat: Francis Lee on Ammonite

Nature may shape the characters of Francis Lee’s rugged, working-class romances, but it’s nurture that ultimately saves them.

In 2017’s “God’s Own Country,” the Yorkshire-bred writer/director made a powerful first impression with a story, set on his home turf, about the attraction that builds between two young men toiling on a sheep farm. An initial sexual encounter between them is frantic, animalistic, two muscular bodies rutting in the cold mud; but with this consummation, the film visibly brightens, as do its characters.

In “Ammonite” (hitting select theaters Friday, followed by a premium-on-demand rollout Dec. 4), Lee continues to explore intimacy as raw human heat, charting the kinds of romantic bonds unexpected and passionate enough to thaw his characters from their gelid, workaday existences. Set on England’s south coast in the early 19th century, it follows real-life paleontologist Mary Anning (Kate Winslet), whose solitary life hunting fossils along the shoreline is disrupted by the arrival of Charlotte Murchison (Saoirse Ronan), a young married woman sent to convalesce by the sea.

Some key differences exist between Lee’s films. “God’s Own Country” takes place in the present day and was shot down the road from the West Yorkshire farm where Lee grew up; “Ammonite” recreates 1840s Dorset, which required Lee to shoot both out of time and off his native moorland. And whereas “God’s Own Country” told of a gay relationship between a British sheep farmer and a Romanian migrant worker, both fictional characters, “Ammonite” excavates an imagined lesbian romance from real history. (While no evidence exists that Anning and Murchison were lovers, Lee points out Anning never had a heterosexual relationship, despite enjoying multiple close and long-lasting friendships with women, and that in her era Anning would have been precluded from documenting any same-sex attraction.)

But taken together, Lee’s films are fascinating in how they consider the relationship between love and labor, exploring the effect of each on body and soul while suggesting intimate connection as one respite available to those who draw only cold comfort from their hard-scrabble vocations. Speaking by phone, the writer/director discussed reaching back through history for “Ammonite,” following his heart after “God’s Own Country,” and why toughness and tenderness make for such unexpectedly fitting bedfellows.

I loved “Ammonite” and “God’s Own Country,” and I’m excited to talk to you about them both. It really does feel like we have to discuss one to discuss the other. They’re both such gentle, tender stories, and very much about tenderness as this almost radical action for characters valued primarily for their physical labor. When did you first know you wanted “Ammonite” to be your next project?

I was actually on the promotional tour for “God’s Own Country,” and I was pretty lonely and a bit sad on my own. I was looking for a polished stone or a fossil for a loved one, as a gift, and I was Googling this. Mary Anning’s name kept coming up, and so I read about her. And her life story instantly struck a chord with me. She was a working-class woman born into a life of poverty, in a totally patriarchal, class-ridden society. She had virtually no access to education; she just went to Sunday school. And, somehow, through her own ingenuity, passion, drive, determination, and will to survive, she rose to being what we’d now call one of the leading paleontologists of her generation.

And there was just a little bit of a parallel there that I felt. I’m not saying I’m as brilliant as Mary Anning, at all, but there was just this thing about me growing up as a working-class kid, not having a great education, being a queer kid, feeling outside of the community. Thinking about me wanting to become a filmmaker was just a ridiculous notion. I didn’t know anyone who’d done that, couldn’t go to film school, didn’t have the finances to do that. So, there was some little parallel there. And at the same time, I knew I didn’t want to write a biopic. I don’t think I’d be good at making a biopic, in that sense. I wanted to write a snapshot of this woman’s life, and I wanted to do something that for me felt like I was respecting her, elevating her to maybe the place she should have been when she was alive.

I knew I wanted to look at an intimate relationship again. I’d read there was no evidence she ever had a relationship with a man, no evidence whatsoever. But there was evidence she had friendships with women, and I thought, ‘How interesting it would be to suggest that maybe that might have been an alternative.’ It was an imagined kind of relationship I wanted to give her, and I felt that if it was with a woman, it would feel more equal. A man in this patriarchal society didn’t feel equal, to me. At the same time, I was reading quite a lot of research about female-and-female relationships in the 18th and 19th century, which were incredibly well-documented by letters they were writing to each other. They were talking about these wonderful, passionate, loving, caring relationships that they were having, and I wanted to look at that as well.

There’s such a bracing immediacy to the films you make, and I was struck by that in “Ammonite.” I know you based the characters of “God’s Own Country” on people you knew, and you’ve said the conflicts related to ones in your own life; there as well you were working with two largely unknown actors. For “Ammonite,” moving back centuries, following two women in a lesbian relationship, working with two much more cemented actresses, how did you reckon with any kind of natural distancing you experienced from those characters, and reconcile the differences between yourself and them—across lines of gender and sexuality as much as time and space?

It’s a really interesting question, because the answer is probably a little bit surprising. “Ammonite” is a much more personal film than “God’s Own Country.” “God’s Own Country,” I did base those two main characters on people I knew, but only right at the beginning. As I wrote and wrote, those characters took on lives of their own. Though the emotions of “God’s Own Country” felt personal, the circumstances weren’t particularly personal. In “Ammonite,” it is much more personal. I don’t know how much more I want to say about that. [laughs]

But “Ammonite” is a deeply personal film, so the emotional sense of it I understood and felt very close to. Their situation, in a sense, I felt very close to. In terms of the stars, I was just really blessed. Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan are fantastic people, and ultimately they cared deeply about the work. They want to do good work, and they want to push themselves. Everything you might imagine comes from being a very successful, famous actor, there was none of that with Kate and Saoirse. They wanted to push themselves, to really mind the truth. I was blessed to work with both of them on an extended process for four and five months before the shoot, developing the characters from the get-go.

All that was off-putting about working with A-list stars is when you go to a small town on the south coast in England, you end up having to contend with paparazzi and crowds of people. And you have your film written about in newspapers before you’ve shot a frame of it. And I found that very difficult. There was a level of discourse around the film, and agendas that were pinned on it—all of these things that didn’t feel to be part of it, for me. When I made “God’s Own Country,” nobody cared. Nobody knew about me or the two actors; we were just on a hill in Yorkshire, doing our thing. That was problematic, and difficult.

One element of “Ammonite” I haven’t seen discussed enough, given what you’re saying about discourse, is the dynamic between love and labor. That feels carried over from “God’s Own Country,” and it’s different from most other period lesbian romances I’ve seen in that you get a stark sense of these characters’ physical differences—specifically, how their bodies are conditioned to survive the social roles this time period thrusts upon them. You cast physical intimacy as this fire that keeps both of them warm in the face of such a cold, inhospitable life—albeit a life Mary chooses and is committed to.

Everything about my filmmaking feels personal. Before I was a filmmaker, I worked at a manual physical job. I worked at a junkyard, and it was a lot of physical, difficult, dirty, horrible work. It really made me think about what we do in terms of our physical labor: how we sell it, and what that does to us physically and emotionally. I thought about juxtaposing that with the softness of a lover, feeling their warmth and care, how that makes you feel. For me, they feel part and parcel, almost, of the same thing. There’s something quite raw about all of that, which resonates with me. I find it fascinating. I’m not romanticizing hard physical labor, believe me. It’s bullshit. It’s not nice. But there is beauty that can still be found in your personal life, despite the way in which your labor causes you so much pain, struggle, and difficulty.

And I feel like the already much-discussed sex scene “Ammonite” builds to is so beautiful in how you watch the characters reconciling those physical differences, healing from that pain, through all this tenderness. They enjoy their bodies and what they can give to each other, as opposed to just utilizing themselves as tools for work. The love languages of your films are so specific with this dynamic of mutual care, which is radical to your characters given the lives they’ve lived before your stories start. What was new to you in “Ammonite” as a filmmaker, in terms of depicting that beauty?

I was really interested in looking at an older character, someone we’d say is in the middle of their lives, who had been through being hurt in a relationship and having their heart broken, what that means and how you move on from that. How do you open up again? How do you find that trust and tenderness, and a commitment to that? Having that kind of emotional and physical memory of what it feels like to be so hurt and destroyed by a love that doesn’t work out, how tentative or closed off you might be, how you might play things differently. In “God’s Own Country,” it was more that idea of first love, experiencing all that initially, and the difference within that.

In terms of the dynamic in “Ammonite,” you explore the idea of maternity, both through the age difference present in the central relationship and the fact that Mary is caring for her own mother (Gemma Jones) in the background. What led you to pursue that concept of mothering, and how it compares and contrasts with other expressions of love? While I can’t speak to this personally, a close lesbian friend of mine who’s seen the film remarked that it captures a very real quality of some lesbian dynamics: this idea of care as a baseline in relationships between women—whether it’s mother-to-daughter, friend-to-friend, or lover-to-lover—and there being overlap in how all three are expressed.

That’s a super complex question I can only speak to personally. Being in a relationship, whether that be with a family member, a lover, or a friend, those dynamics shift all the time. That’s true whether or not it’s a sexy dynamic, and you want to jump on the bones of somebody, or a caring dynamic, and you just want to wrap someone up in a blanket and make them feel better. For me, the most successful relationships are those where it can go in between those things. You can be the teacher one day, and the student the next. Or you can be the lover one day, and the advisor the next day. That’s how I’ve seen my relationships. Oh, god, this is all about me, isn’t it? But that is how I’ve seen my relationships, in terms of those shifting dynamics. And not to divulge too much, but I’m also fairly obsessed with the dynamics between parents and children, and how that can play out.

“Ammonite” arrives to select theaters on November 13, and will be available on premium on demand on December 4.