Leather Balls and 3,000-Year-Old Pants Hint at an Ancient Asian Sport

A little over 3,000 years ago, a roughly 40-year-old man was laid to rest in a cemetery in what is now the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region in Northwest China. He was wearing fancy pants. Possibly the oldest trousers in the world, they had an enlarged crotch area, indicating he spent a lot of time on horseback. A pair of red leather boots completed the ancient ensemble.

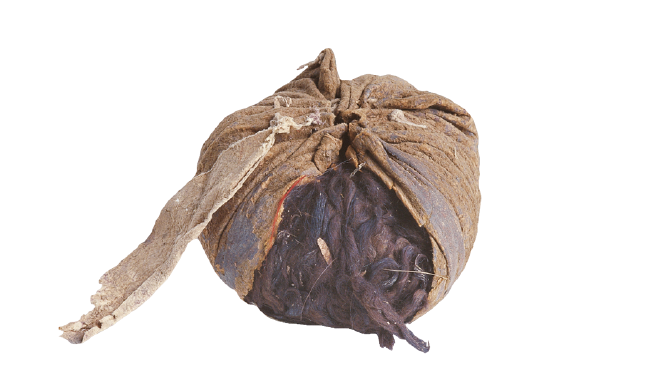

But perhaps the most curious component of the grave was a leather ball, around the size of a human fist. When it was excavated in the 1970s, no one knew how old the tomb was. Now, the leather balls have finally been dated to approximately the same period as the pants. The results were published in the open-access Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

“We can now confirm that these three leather balls from Yanghai are the oldest leather balls in Eurasia,” says Patrick Wertmann, an archaeologist at the University of Zurich and lead author of the recent study. “They were life tools, used for play or useful training.”

The grave in question is just one of 3,000 found at Yanghai, in the Turpan Basin. Since 2003, just over 500 of the graves have been excavated, and three of them—including the tomb of the well-to-do horseman—yielded the balls, two of which were marked with a red cross.

In the first millennium BC, Yanghai was home to a sophisticated community of horseback riders. Wertmann says they were some of the earliest horse domesticators in the area, and that the presence of the balls—and the depiction of horseback ball games elsewhere in China—suggests that the balls may have been used for sport. The Yanghai Tombs, as they are known, span nearly 1,400 years, and most have been well-preserved. The most recent date to the Han Dynasty, or roughly the 2nd century. The site offers archaeologists a glimpse of what mattered to these ancient riders, from their riding trousers to their red-leather boots.

“The whole Turpan Basin is like a treasure trove because of the climate conditions,” Wertmann says. “It’s extremely hot and extremely dry. For us as archaeologists it’s really good, because all these organic materials are naturally preserved, including textiles, leather, wood, and also the human animal and plant remains that are not usually preserved in archaeological contexts.”

The balls—which are stuffed with wool and hair, wrapped in treated rawhide, and crimped closed on top—look a lot like large soup dumplings. They’re half a millennium older than other excavated balls from Eurasia, according to Wertmann. At least one of the balls had strike marks and had apparently burst open, perhaps after it was struck in a game. The red crosses—which also show up in later Chinese art depicting stick-and-ball games—may have been painted to help the tan balls stand out from the brown landscape.

The balls were no joke. “They’re actually really hard,” Wertmann says. “You could compare these leather balls from Yanghai with modern baseballs.”

More recent art from elsewhere in China shows polo-like games being played on horseback with sticks. Curved wooden sticks were also found in some graves in Yanghai, though they are younger than the leather balls, so the two were not necessarily used in tandem.

“I appreciate how cautious the authors are in their interpretations of these balls, essentially saying we cannot determine based on current evidence that these balls can be linked with polo,” says Jeffrey Blomster, an archaeologist at George Washington University who has worked on numerous ball-game sites in Mesoamerica, and who is unaffiliated with the recent paper. “While we cannot say for sure what kind of game, or even activity, was performed using these balls, the fact that all three are nearly the same size suggests a similar use for all three.”

With thousands of graves left to excavate at Yanghai, archaeologists may learn more about the exact purpose of these balls. The elements of sport are there, and for the researchers who study them, the game’s afoot.