How Berlin Is Reckoning With Germany’s Colonial Past

It’s difficult to imagine today what colonial, Prussian-era Berlin looked like, as one walks around the city’s central district, now dominated by the block-shaped architecture of the old East Germany. But that’s exactly what activists and community organizers are trying to get people to do, to see Germany as it was when the country was among the 13 European colonial powers, plus the United States, that carved up Africa among themselves. The site of Otto von Bismarck’s office and residence is on Wilhelmstraße, and it’s where the man called the Iron Chancellor opened the Berlin Conference in November 1884. It was there that, in just a little more than three months, most of the borders that still divide Africa today were decided.

Brandenburger Tor is a commanding presence of old Berlin, the famed gate built in the 18th century by order of Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm II, whose name marks a street that runs perpendicular to the monument. It’s a popular spot for tour groups, as a gateway to other notable Berlin landmarks: Tiergarten, a lush park filled with statues and monuments dedicated to figures such as Goethe and Beethoven, and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, a five-minute walk south. The city is also overlaid with a number of statues, plaques, and street names that conjure a more overlooked aspect of its past: colonialism. This history is still widely unknown: not taught in schools, lacking significant memorials. But in recent years, there has been a strong push from activists, organizers, and historians to change this.

Bill is a journalist and historian who’s lived in Berlin for almost 20 years. He’s using a pseudonym so he doesn’t draw negative attention from German funding bodies for his critical Anti-Colonial Berlin tour—one example of the city’s activist push to present a more complete picture of its past. He begins the tour at Brandenburger Tor by highlighting some of the lesser-known but prominent Afro-German figures of the anticolonial movement. They lived and worked in the country at a time that is often portrayed as overwhelmingly white, underscoring the idea that individuals and socioeconomic movements had been working to dismantle colonialism since its inception.

Bill talks about people such as George Padmore, who was born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse in Trinidad. A Pan-Africanist writer, activist, and communist, he is among the figures who confronts the myth of a racially and politically monolithic German history. Padmore had joined the Communist Party when he moved to the United States in the 1920s, before relocating to Hamburg in 1931, where he cofounded the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers.

“Black workers from all over the world could fight together in Africa, in the European diaspora, in the New World,” Bill says. “They even published an international newspaper called The Negro Worker, which was based out of Hamburg.”

Padmore fled Germany after his offices were ransacked by ultra-nationalist gangs in 1933, during the rise of the Nazism. He eventually went on to become a theorist of the African independence movement, and later advised Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister and president of an independent Ghana.

While Germany may not have had as many colonies or subjects as Britain, France, and Belgium, it did participate in the trade, ownership, and genocide of enslaved people, in places such as Groß Friedrichsburg, a Brandenburg-Prussian trading post based in the Gold Coast (Ghana). From that fort, Germany traded nearly 30,000 enslaved people to the Americas, before the site was sold to the Dutch West India Trading Company in 1717.

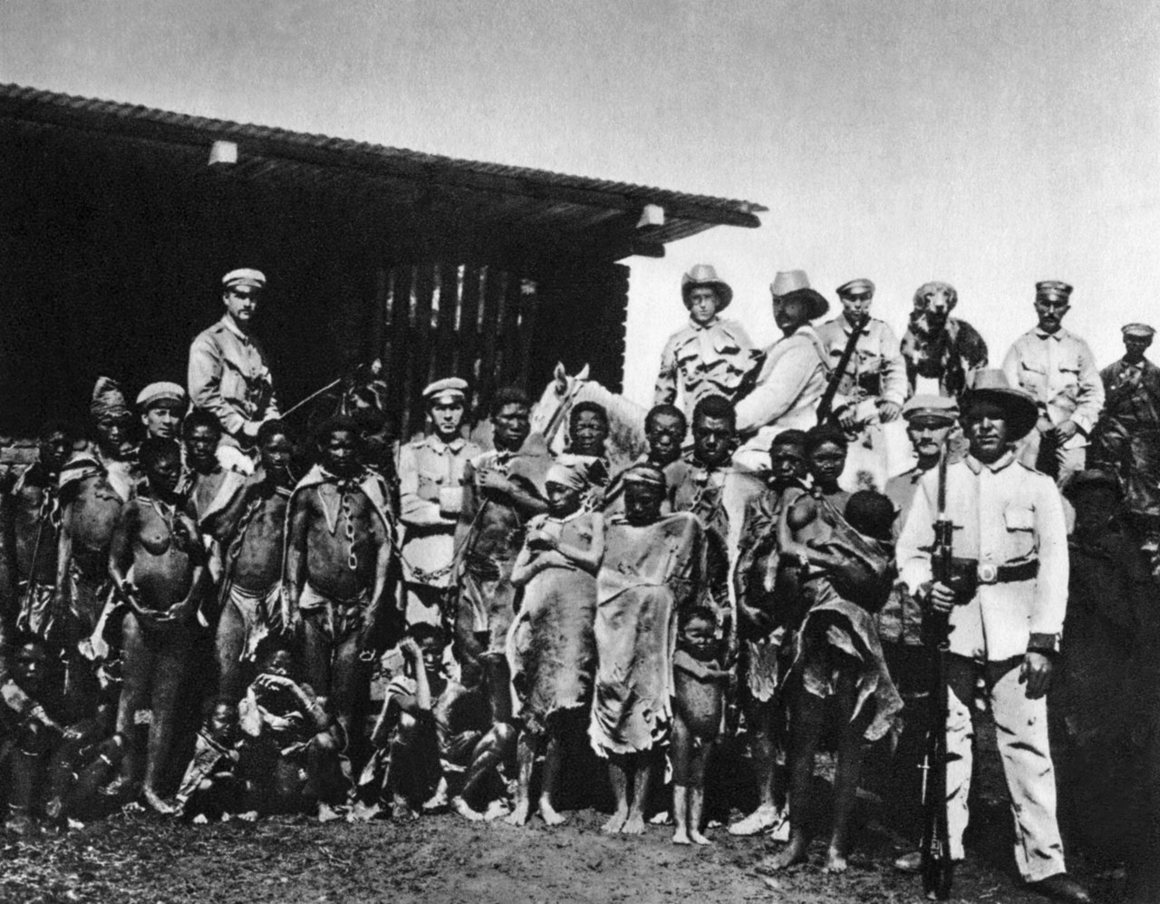

Germany’s role in colonialism, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, is often overshadowed by the Holocaust. But that wasn’t the first genocide of the 20th century—that took place in Namibia, formerly known as German South West Africa. From 1904 to 1908, an estimated 75,000 Herero and Nama people were shot, starved, tortured, and died in the world’s first death camp, on Shark Island. There, German colonial forces exterminated 80 percent and 50 percent of those ethnic groups, respectively. It was an atrocity for which the German government recently offered €10 million in compensation, while also announcing a €600 million expenditure to reconstruct the palace of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the Prussian imperial leader ultimately responsible for the genocide.

“The connection between the genocide in Namibia and the Holocaust is interesting on a lot of levels,” says Bill, in front of a building on Wilhelmstraße where the office and residence of Bismarck once stood. “On the one hand, there’s a lot of personal continuity,” he says. “A lot of people who orchestrated the Namibian genocide later played a role during the Nazi regime. They got their start working in colonial expeditions.”

Tiffany Florvil, a cultural historian of 20th-century Germany and author of Mobilizing Black Germany, sees that continuity as well. “They don’t recognize that the architects of the Holocaust, [people such as] Eugen Fischer, are talking about the Nama and Herero people in degrading and derogatory ways that were then later applied to Jews. He was a big honcho pushing his pseudo-scientist views to propel Nazi ideology to justify the exclusion and then the extermination of Jews.”

In fact, Fischer, an anthropologist, went to Namibia to study phrenology, the debunked science that used skull size to draw conclusions about psychological and intellectual differences between ethnic groups. Not only were more than 3,000 Herero and Nama skulls sent to Germany for study at universities, sold as keepsakes, or displayed in museums, but many of them were boiled, cleaned, and prepared by Herero and Nama people themselves.

“The creepy thing is that it’s a very small minority of these skulls that ended up in [museum] collections,” says Bill, on the way to the tour’s final stop. “Untold numbers ended up in people’s attics and private collections. It wasn’t uncommon for someone to be cleaning out grandpa’s attic and to find a human skull just lying around.”

Rather than spurning colonizers such as Fischer, Berlin’s “African Quarter” in Wedding, a neighborhood with a high concentration of Black residents, honors them with street names. Lüderitzstraße, for example, is named for Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz, the founder of German South West Africa (Namibia). Nachtigalplatz is named for Gustav Nachtigal, the founder of the German colonies in Togo and Cameroon. And Petersallee is named for German Imperial High Commissioner Carl Peters, founder of former German East Africa, now Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania. The latter used local girls as concubines, destroyed whole villages, and routinely hung rebellious locals for treason. After his monstrous activities were made public in 1896 by socialist politician August Bebel, he was dishonorably relieved of his position, but evaded a final sentence by relocating to London.

“[Peters] was recalled from his post and left in disgrace,” says Bill. “I cannot emphasize this enough, not for committing mass murder, but because of his personal behavior while committing mass murder.”

Wedding isn’t the only place with colonial monuments. A 26-page document compiled by AfricAvenir International, a Berlin-based nonprofit, reveals dozens more, all over the city—from Wissmannstraße, named after colonial administrator Hermann Wissmann in Neukölln, to Otto von Bismarck Platz, Allee, and Straße, to Takustraße, which commemorates Germany’s even lesser known colonial expeditions in Asia. Tahir Della, of the nonprofits Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland and Decolonize Berlin e.V., is one of numerous Afro-German people who are currently fighting to change that.

For years, Della and countless others have been pushing to change these racist street names and advocating for a public acknowledgement of the country’s colonial past. The former has seen some recent success. The latter presents a bigger challenge.

Lüderitzstraße will soon be named after Cornelius Frederiks, a Namibian resistance fighter, Nachtigalplatz will be named after Cameroonian King Rudolf Magna Bell, and Petersallee will be split up and given two new names, one for Namibian independence fighter Anna Mungunda and the second to Maji-Maji-Allee, after the Maji-Maji Rebellion, which took place in the early 20th century in what was then German East Africa.

“These are things people didn’t even think about five or 10 years ago,” says Della. “But we’re past the point of no return now.”

He believes that Germany’s current attitudes, institutions, and structures are built upon a legacy of racism that most Germans simply don’t know anything about, which he finds frustrating, because it’s a history that continues to support racism and disenfranchise Black people living in Germany today.

“This [ignorance] is a continuation of history, from colonialism, to fascism, and modern times. It’s very important to bring these things together,” he says. “Without the concentration camps in Namibia, Germany could not have imagined the Holocaust. They are connected.”

Perhaps the biggest indication of a shift in public attitude happened in August 2020, when the Mitte district council announced that it would finally rename Mohrenstraße or “Moor Street” (commonly abbreviated to M-Strasse) to Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Straße, after the Afro-Prussian noble of the same name, who was born in Ghana and sold into slavery before becoming Germany’s first Black scholar.

It’s a start, but Decolonize Berlin e.V. says that it’s not enough, and not a truly critical examination of Germany’s colonial past. That’s why the city of Berlin has now agreed to fund a city-wide project to encourage this reflection through education, memorials, and events, scheduled to run through 2021.

“We need decentralized memorials all over Germany and Europe to confront people, but also to make it visible, so that people can access [that history]. The Stolpersteine is a good example,” he says, referring to the project that has placed thousands of brass pavers into footpaths throughout European countries such as Germany, Norway, and Czechia in front of the homes from which the Nazis forced people, including Jews, Sinti, Roma, and homosexuals. “These [anti-colonial] memorials should be all over Berlin.”

Della wants their project to offer a stark contrast to colonial memorials all over the city, showing what many hope to be a more complete picture of Germany’s history, one that honors the suffering and resistance that is just as much a part of the country’s story.

Florvil would like to see some of Berlin’s colonial landmarks renamed to honor more of the Afro-German activist women as well, such as Katharina Oguntoye and Marion Kraft, who have fought and continue to fight for greater awareness.

“There are countless women in the movement who have done amazing things,” she says. “Seeing that on a street corner has so much significance on a variety of levels. That would be so symbolic for many people.”

While a tour isn’t enough to decolonize a massive city, it does represent a resource in the ongoing spatial politics of race, history, and the path that Germany claims it wants to take toward a more inclusive society.

“To decolonize this city means acknowledging that whiteness is not the norm,” says Florvil. “To challenge the status quo of European representation, it means a reckoning with colonialism, a reckoning with the legacies, and erasing whiteness from a landscape that’s been constructed as white even though it’s never been completely white.”

* Correction: This caption originally suggested that the street’s name had already been changed. At press time, the change had not been made official yet.