Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” is a celebration of three real-life Black artists and legends. There’s the blues singer, often referred to as the “Mother of the Blues,” whose name and song give the film its title. There’s the author, August Wilson who, inspired by Rainey and the era she found fame in, crafted his 1984 play around her larger-than-life persona. And there’s Chadwick Boseman, taken from us way too soon, who chose this difficult material to play while living with cancer. We’ll never know if Boseman knew this would be his swan song; the fact that it is haunts the viewer, especially during one particular monologue. Boseman never gave less than one hundred percent to his often demanding roles. His work here as the trumpet player, Levee, is no exception. It’s no stretch to say his last performance may be his finest.

Levee is a fast-talking, ambitious charmer, as quick with his horn as he is with a come-on line. He’s old enough to know better, but young enough to think he can outrun the consequences of his actions. Levee has loftier goals than his current job as a member of the backing band of Ma Rainey (Viola Davis). He wants to arrange existing songs and compose his own music, something Sturdyvant (Jonny Coyne), the manager of this recording session seems to encourage. Levee has even sweet-talked his way into forcing the band to cover his arrangement of the titular song, despite the success of its original incarnation. This is bound to cause dissent, because as Cutler (Colman Domingo), the trombonist points out, Ma ultimately calls all the shots, not Levee. This musical ensemble has two divas, yet only one of them is the genuine article.

Played onstage in the original 1984 production and its 2003 revival (both of which I have seen) by Charles S. Dutton, Levee is only as sweet and charismatic as the situation he is in requires. Underneath an exterior that’s primarily a performance is a white-hot coil of rage that scars his soul the way a White man’s knife scarred his body In childhood. The underrated Dutton, a bigger man than Boseman, played that anger a bit closer to the surface. Here, Boseman uses his more wiry frame and Cheshire cat grin more seductively and in hypnotic fashion, like a cobra charming his victim before that lethal strike. “I can smile and say ‘yes, sir’ to whomever I please,” he says in one of the two big speeches screenwriter Ruben Santiago-Hudson adapts from Wilson’s play. “I got my time coming.”

Levee and Ma are the live wires, but the rest of the band is more pragmatic, either due to age, wisdom or merely wanting to get in and out as quickly as possible. In addition to Cutler, who serves as the boss by proxy, there’s the bassist Slow Drag (Michael Potts) and the piano player, Toledo (Glynn Turman). They’re the first three to arrive, meeting Ma’s agent Irvin (Jeremy Shamos) at the rather rundown recording studio where they are to record an album of Ma’s biggest numbers (and a Bessie Smith cover or two, which is sure to ruffle Ma’s feathers). Cinematographer Tobias A. Schliessler makes an early contrast between the outside world and the dank basement of the studio by bathing a shot of Cutler, Slow Drag and Toledo crossing the street in a preternatural beauty that calls attention to its fakery. This is the same spot where we’ll meet Ma Rainey, though under far more realistic-looking circumstances. Our introduction to the singer occurs after someone crashes into her new car.

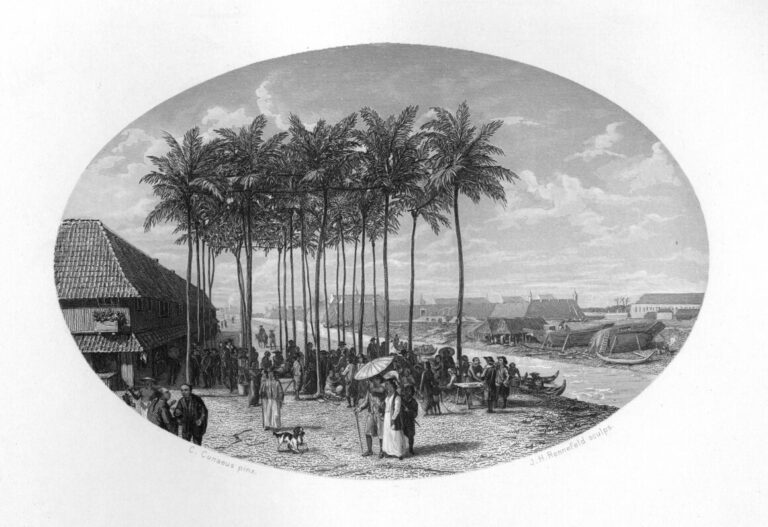

Before the star’s arrival, Levee joins the group holding his new $10 pair of shoes, which were partially paid for by his winnings in a band card game the night before. The men shoot the breeze, often with a bit of tension, and at one point, the wind blows toward a story about a colored man who sold his soul to the Devil. The sale made him somewhat untouchable, allowing him to get away with murder and other, much smaller infractions that would easily have gotten him arrested or lynched. Wilson’s penchant for sprinkling symbolically supernatural elements into his plays gets an amusing, ironic tinge here—it seems the only way for a Black man to enjoy the same freedom as his White counterpart in the 1920’s is to broker a deal with Beelzebub. This story also informs us of Cutler’s extremely religious background, a key factor in the film’s most devastating sequence.

Eventually, Ma arrives, covered in greasepaint, pissed off about her car and lugging along Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige), her latest side piece. Rainey made no attempts to hide her sexual enjoyment of women; in “Prove it on Me Blues,” she sang “went out last night, with a crowd of my friends. It must have been women, cuz I don’t like no mens.” Though Dussie Mae is way too flirty, the band members know she’s off limits. Everyone, except Levee, that is. Unlike the guy in that Satanic story, Ma doesn’t need to sell her soul to have power to throw around. All she needs to do is sell records. And while Irvin bears the brunt of her tantrums, little sympathy is afforded him because he’ll still get the sweeter end of the deal if he bears that abuse. “All they care about is my voice,” says Ma. So, why not make them earn it? “They hear it come out,” she says of White people listening to the blues, “but they don’t know how it got there.”

One of Ma’s requirements before she records “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” is to have her nephew Sylvester (Dusan Brown) do the spoken introduction to the song. Levee’s arrangement doesn’t have this feature—it’s a faster, more swingy number that correctly hints at the musical trends that will follow—but Ma predictably vetoes his input. The song is to be recorded as she performs it for her fans, primarily so Sylvester can earn some money for his input. This presents a problem that, for once, unites Levee and the others, but their protests are short-lived. Everybody knows whose Black Bottom it is, and what she says goes. Davis, in her most grandiose cinematic role, relishes the opportunity to be difficult, self-assured and dominant. Even in the quieter moments, her Ma Rainey fills up the room. It’s a delectably grand performance that reunites her with her “Get On Up” co-star.

It wouldn’t be August Wilson without great speeches. “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” has several, and Hudson keeps the author’s generosity in dispensing them to all the main characters. Toledo has a fantastic monologue using food and cooking as symbols for the plight of Black people in America. “The colored man, he’s the leftovers,” he says solemnly at the end of his moment. The elder Toledo rubs Levee the wrong way with his commentary, and at first, he comes off like some Respectability Negro telling the youth to pull up their pants and stop partying if they want respect. But, Wilson gives him another moment where he talks of his past and how he went down the same avenues Levee is going down, except he knows which ones are dead ends. Levee’s belief that Sturdyvant will let him record his own songs is one of those dead ends. Toledo knows this, because he’s been around the block more times than his colleague, but his cynicism will go unheeded. Much will be made of Boseman and Davis’ work here, but Turman’s excellent work is also worthy of notice.

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” saves its most emotional moments for Levee, however, and Boseman devours them with a ferocity that sears the screen. Before his biggest scene, director George C. Wolfe does something rather magnificent. He trains his camera on Boseman listening to a conversation going on in another room. The scene is silent, but a wave of emotions play across Boseman’s face. Wolfe patiently waits for them to subside. It’s a superb yet subtle piece of acting, the calm before the storm, so that when Levee finally explodes, the viewer is suitably rattled.

The ensuing monologue is a companion piece to an earlier one, where Levee describes witnessing the horrific violation of his mother by eight or nine white men. They only stopped when one of the men cut the young Levee’s chest, scarring him for life. This follow-up speech, however, is even more haunting and terrifying, with Levee raging against Cutler’s religiosity, asking him where his God was when this horrible thing was happening. It’s in this moment that the distance between actor, viewer and role fractures: Boseman knew he was dying when he performed this monologue, and some of the things he’s saying as Levee sound like questions one would ask oneself if facing one’s own mortality. Suddenly, the emotions become too real. Boseman practically levitates with hurt and rage, committing to the moment with a ferocity that’s as brilliant as it is painfully unwatchable. I know it’s just acting, but for me, reality intervened in that moment and I saw something transcendent.

August Wilson has an affinity for musical instruments—they comprise the titles of two of his plays—and musicians, as all of his plays have some lyrical element, even if it’s just in the words. I think there’s a special place in his heart for trumpet players. One of them shows up in producer Denzel Washington’s own adaptation, “Fences,” and his main character here is a guy who hopes his trumpet is his ticket to the big time. Both plays end with the sound of trumpets, but in “Fences,” Gabriel’s horn opens the gates of Heaven for Troy Maxson. In “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” the fruits of Levee’s horn blow him in the other direction. His condemnation arrives in the form of a White band eventually playing the music he one called his own. This is the bitter irony of the play, a tragic commentary on the realities facing Black musicians of the day. Sturdyvant offers Levee five bucks a song, but he won’t let him record them. The parallels between this outcome and the earlier deal with the Devil story are evident, except the guy in that tale sold his soul willingly. And he got something for it.

Opening in select theaters on November 25th and on Netflix on December 18th.