A Tale of Survival, Wrapped in a 19th-Century Reindeer-Skin Sleeping Bag

In 2013, Barnum Museum curator Adrienne St. Pierre discovered what she described as a “rather decrepit old cardboard box” in the museum’s offsite storage facility. Inside was a huge ball of russet animal skin, noticeably aged and with loose bits of fur poking out in wayward tufts.

Intrigued, St. Pierre brought the box back to the Museum, and carefully began unfolding the fragile leather in order to identify it. Stitched together from caribou skin, the object bore a stained label whose faded handwriting finally revealed its purpose and history: “Sleeping bag,” it read, “from the Greely Expedition (U.S. Steamer Bear sent to their rescue.)”

The seemingly ordinary lump of fur had been part of one of the best-known expeditions of the late 19th century, a wild survival story and a landmark in environmental science.

Exploration culture was popular by the 1880s for good reason: a foreign expedition had long been part of the standard toolkit for eager colonizers, an attractive venture for ambitious explorers and their financial backers, and popular with a reading public who liked true-life adventure tales in their morning papers. In an effort to leverage exploratory fever for the sake of science, 11 countries combined to declare 1882-1883 an “International Polar Year.” These nations launched 14 coordinated expeditions to explore the polar regions and collect synchronized data on climate, geography and astronomy.

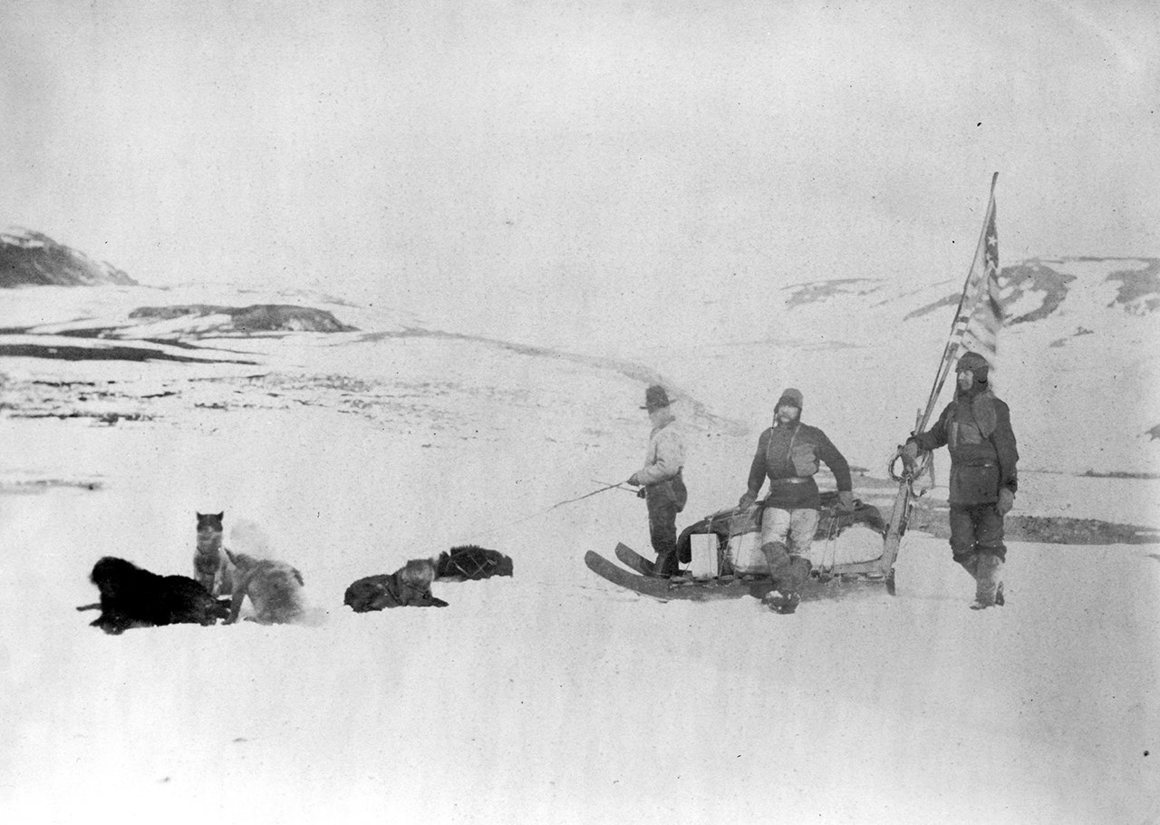

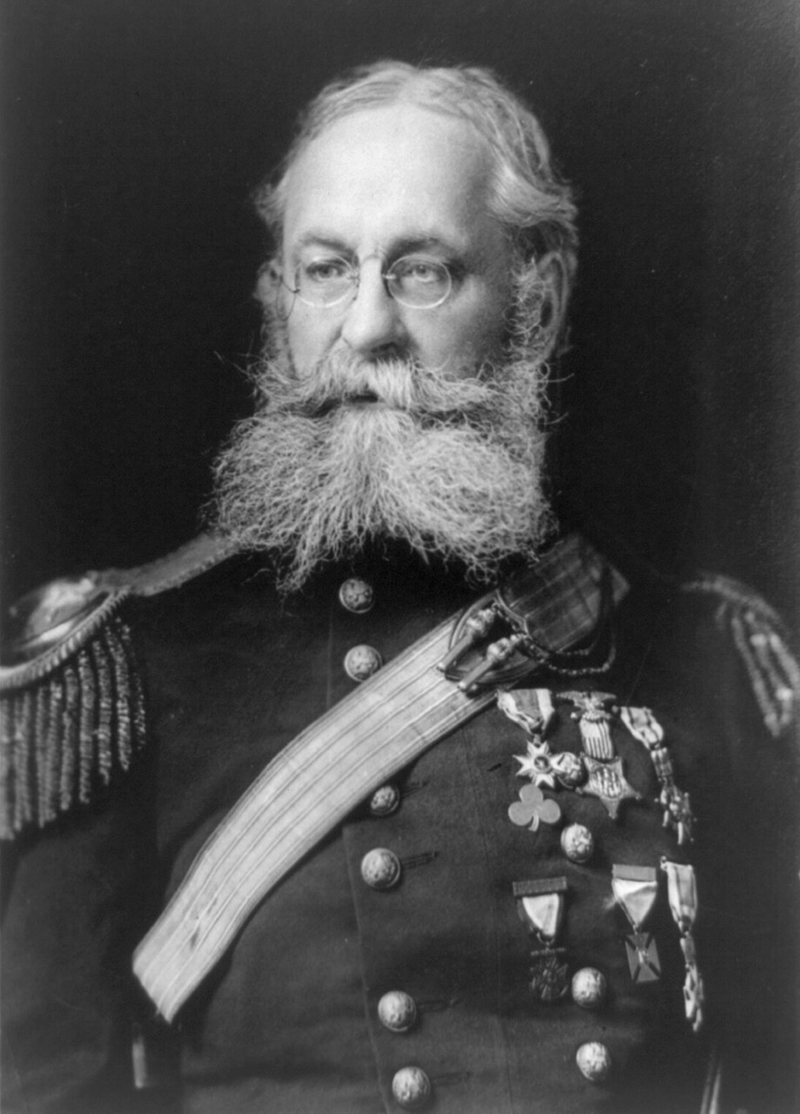

As part of this project, an American expedition led by former Union Army officer Lieutenant Adolphus Greely established a Polar Year station on Ellesmere Island, off the northwest coast of Greenland. The team built a long rectangular structure with space for bunks, dining, bathing, and collecting scientific measurements, named it Fort Conger, and set in for two years of study. Arctic research was hard work (one does not envy the man who had to sit in the outhouse-style data collection shed) but gratifying. The crew ran experiments, hunted musk oxen and seal for fresh meat, and explored their surroundings, venturing farther north than anyone had ever been.

Things seemed to be going well, but the ship route to Ellesmere was only accessible for a short time during the summer. The rest of the time, ice blocked the passage, and ships ran a substantial risk of being trapped and broken if they tried to pass at the wrong interval. The expedition’s success depended on ships being able to reach the party with supplies and refreshed rations each August. One ship was due to re-supply the team in August 1882, and another would bring them home the following summer. Neither ship arrived—one could not pass the ice, and another sank after being crushed.

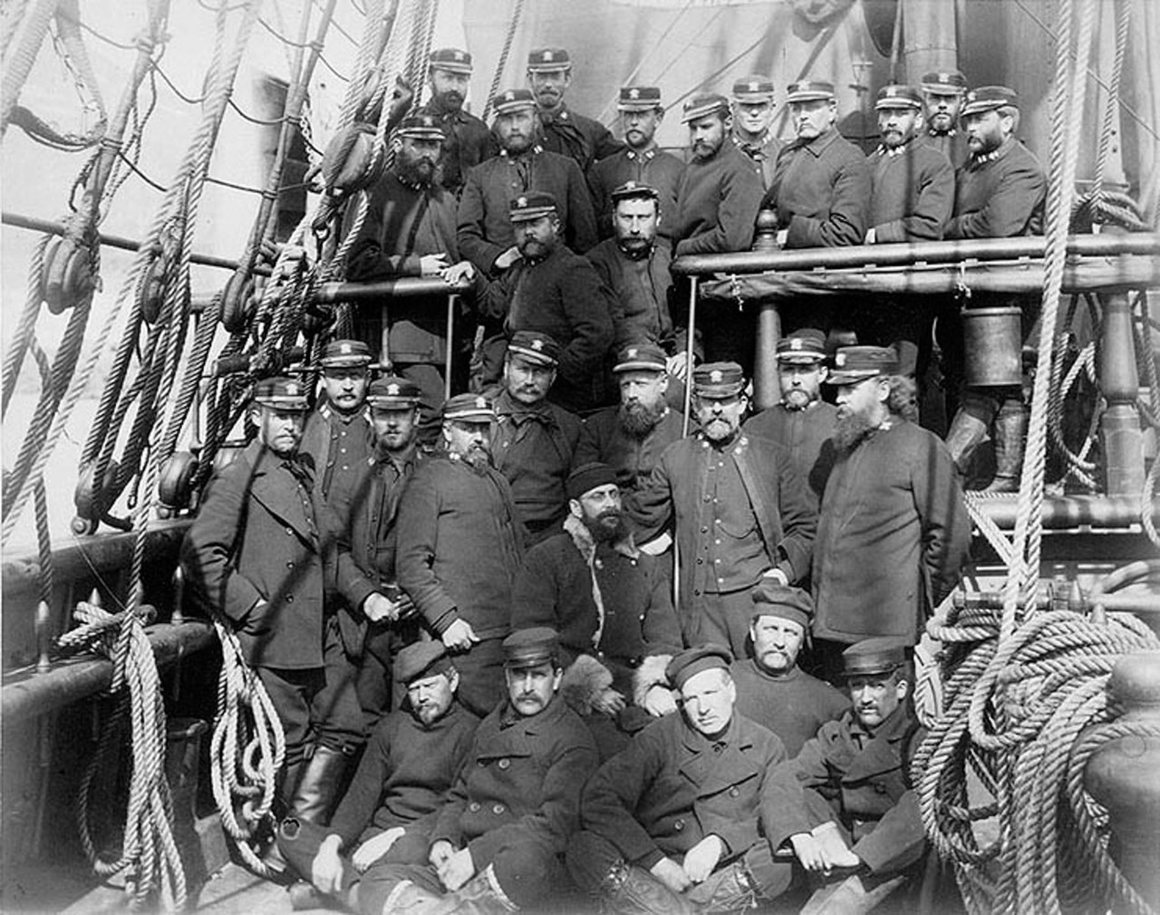

Frugality and seal steaks could no longer save the day, so the U.S. Navy was ordered to retrieve the Greely expedition, no matter the cost. The Navy procured sledging equipment and frozen meat, and re-fitted two hunting ships for the journey, so that one could continue if the second was damaged or destroyed. Greely’s men had taken sleeping bags made from buffalo skin; the Navy ordered caribou hide from Sweden to make better allowance for the punishing Arctic weather. The Barnum Museum’s bag was sewn on these orders, as a roughly eight-foot-long pouch of reindeer skin with the fur on the inside.)

Desperately short on rations and despairing of rescue, Greely and his group abandoned post in August 1883 and made it 200 miles south to Cape Sabine, where they hoped to access supply caches or rescue ships. They built a makeshift shelter using a boat for a roof, and expected to stretch their meager 40 days of rations as far as March of 1884.

Rescue did not come until June. When the Navy rescue ships arrived (with the Museum’s sleeping bag aboard) they found seven men huddled in a single shredded tent, the few survivors of Greely’s original crew of 25. A succession of men had died of cold and starvation as rations disappeared, and before long the crew resorted to eating their sealskin shoes—and considering cannibalism to survive. Greely himself shot one of the party for stealing food.

Wrapped in reindeer skin and shock, Greely and five of his men remained when the relief party returned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Another member of the expedition died on the return voyage.) Because media had made a sensation of the dramatic survival story, various and sundry items from the ship soon made their way to eager souvenir-seekers. The story remained so popular that the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair featured a diorama of the survival scene.

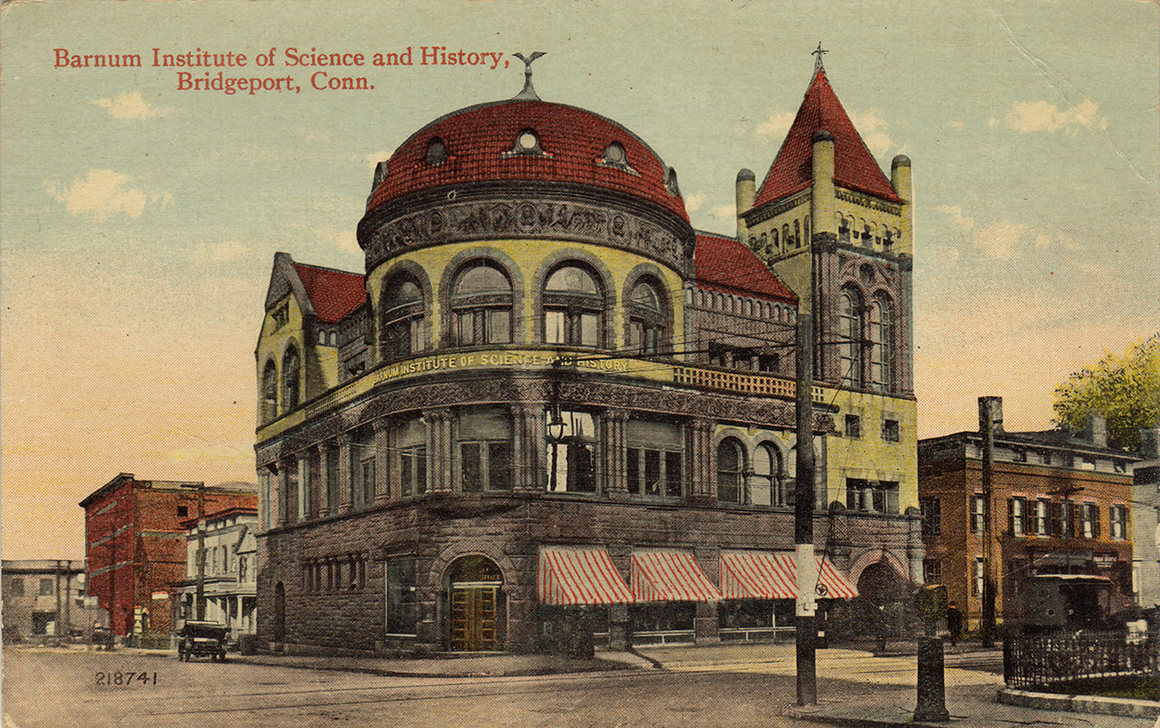

In 1890, with the expedition and its breathless media coverage still fresh, the showman (and 21st-century karaoke icon) Phineas Taylor Barnum was considering his lasting legacy. That he would choose a museum as a final project may seem surprising to people who know Barnum only for the circus, but according to Barnum Museum director Kathleen Maher, it is entirely appropriate. “Barnum’s lifelong mission was instructive entertainment,” she notes, “and few people realize the depth of his contribution to the modern museum model.” Barnum, whose American Museum first brought him to fame, built his last museum in Bridgeport, Connecticut as a celebration of American ingenuity, and a gift to local scientific and historical organizations lacking a permanent home. The caribou sleeping bag was donated by the family of a local Navy veteran in 1890, a year before Barnum’s death and three years before the museum opened.

The sleeping bag is still kept at the Barnum Museum, where it represents the Greely expedition’s contributions to modern science. The expedition collected information on broad swaths of geology, geography and climate – recording daily and even hourly measurements on temperature, precipitation, barometric readings, tides and the contours of the polar day. Amid some of the worst conditions imaginable, the expedition crew went to great lengths to preserve their data and instruments, intent that their research should survive even if they did not. Their findings serve as a valuable baseline in the modern understanding of global climate change.

According to St. Pierre, this connection to the present is perhaps the sleeping bag’s greatest significance. “I was intrigued by the idea that a tattered, 135-year-old reindeer-hide sleeping bag could be made relevant to today’s audiences, who may be very familiar with the phrase ‘global warming’ but not realize how climate science—in fact how our understanding of climate as a global system—came into being,” she says. “I suspect many people have an ‘ah-ha’ moment when they learn about the Polar Year. It was revolutionary!”