The Deadly Temptation of the Oregon Trail Shortcut

In the summer of 1846, a party of 89 emigrants was making its way westward along the 2,170-mile-long Oregon Trail. Tired, hungry, and trailing behind schedule, they decided at Fort Bridger, Wyoming to travel to their final destination of California by shortcut. The “Hastings Cutoff” they chose was an alternative route that its namesake, Lansford Hastings, claimed would shave at least 300 miles off the journey. The party believed this detour could save more than a month’s time. They were wrong.

Hastings Cutoff turned out to be a waterless, wide-open stretch of the Great Salt Lake Desert, bordered by sagebrush wilderness, that began with having to forge their own wagon route through Emigration Canyon in the Wasatch mountains. By the time the party finally reached the Sierra Nevada mountains, the shortcut had cost them weeks. Snow fell, trapping the Donner-Reed party. This is when the most infamous (and deadly) part of their tale began. When members of the party began starving to death, survivors ate their remains to stay alive.

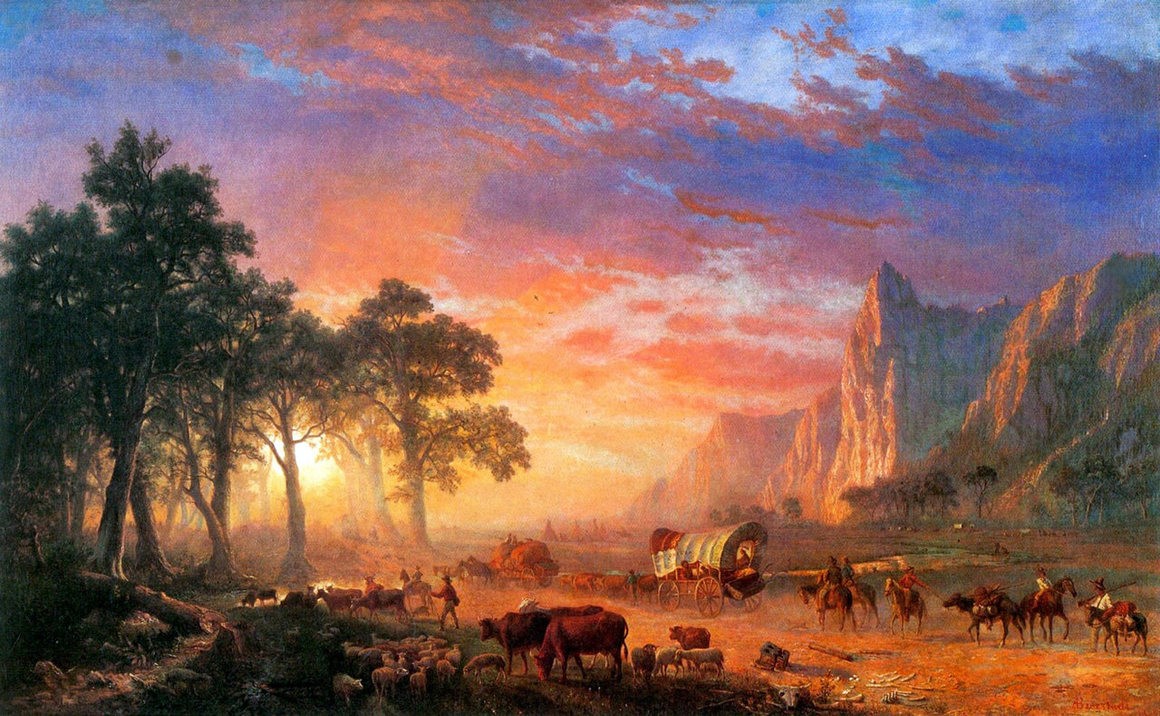

Shortcuts, or quicker, supposedly easier ways of doing something, have often produced disastrous results. But perhaps nowhere are the calamities more prevalent than across the American West during the 19th century. That’s when hundreds-of-thousands of settlers migrated from the Eastern United States to what’s now California and Oregon, hoping to procure their own tract of land and perhaps make a better living in the American frontier, where the possibilities seemed endless.

“It’s obvious that [emigrants traveling west] were in need of shorter routes to save time and money,” says Rob Sweeten, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Administrator for the Old Spanish National Historic Trail. “Especially when you figure, they’re traveling 15 miles a day and facing challenges like changing weather and river conditions, greedy landowners, and conflicts with Native Americans.”(By and large, Native Americans tolerated the many travelers barreling through their land, but occasionally they defended it more actively. Between 1840 and 1860, Native Americans killed 362 emigrants along the trail, while emigrants killed 426 Native Americans.)

The more popular a trail became, Sweeten says, the more notorious it grew among travelers. Emigrants shared tales about highway robbers, entrepreneurial souls who’d begun extorting exuberant fees at river crossings, forcing them to either come to an agreement or go miles out of their way. “Such difficulties often led to them attempting to find an easier route, shorter route,” says Sweeten. “Though, in many cases, the new route turned out to be much harder.”

That’s exactly what happened to the Donner-Reed Party in 1846, when they found themselves trailing well behind other emigrants and decided to put their trust in Hastings. “Hastings’ motivation for the cutoff was pure capitalism,” says Sweeten. With California part of Mexican territory at the time, Hastings saw huge potential in settling the land and perhaps even making it an independent republic. “He figured that if he could get people to come to his communities and the specific areas that he mapped and created, by cutting across the Great Basin and arriving into what’s now the Sacramento area, then he might even become king of this new republic,” Sweeten says.

To encourage settlers, Hastings penned a guidebook called The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California. It touted the American West as a virtual Garden of Eden, and claimed his cutoff to be the “most direct route” to the San Francisco Bay Area. But the one thing he didn’t do? Test the cutoff himself before making the claim. Existing trails followed centuries-old paths established by animals and maintained by the local Shoshone people. The cutoff, though faster in theory, was new and full of treachery.

“He simply looked at a map of the route that settler John C. Fremont had taken in 1845 across the Great Salt Lake Desert, and said it would be quicker and easier than continuing along the standard trail,” says Sweeten. “What he didn’t realize was that Fremont almost died doing it.”

Hoping to get some sense of the extreme hardships that the Donner-Reed party endured, three former Bureau of Land Management (BLM) interns, including expedition leader Michael Knight, spent a few days hiking a portion of the Hastings Cutoff in 2014—in 102-degree heat. There was one thing Knight realized almost immediately: “They put a lot of faith and trust into this guy that they never met,” Knight says, “and their lives were essentially in Hastings’ hands.”

Knight says that except for several segments of historic trail ruts that remain visible, and the addition of Interstate 80, which runs directly across the shortcut, the landscape surrounding Hastings Cutoff appears pretty much the same as it did when the Donner-Reed party crossed it more than 150 years ago. Mirages still pop up unexpectedly, like phantom lakes and rocks resembling lost cattle across the great salt flats, and the crust-covered mud flats that would swallow up the settlers’ covered wagons to their axis can still easily consume an occasional hiking boot or two. “While we were walking across them I noticed how crunchy and soft the terrain was, and thought, ‘this would be so rough to pull a wagon on.’ It isn’t so bad for one person but to be towing all of your life’s belongings along with you? That could be really terrible.” There are also rattlesnakes, scorpions, and horned lizards to contend with, and a 90-mile stretch with no potable water that remains vast, exposed, and with nothing around for miles.

The Donner-Reed party had been hoping for a bit of reprieve. Hastings Cutoff turned out to be the exact opposite. But shortcuts and risk-taking went hand-in-hand on the Oregon Trail.

Take the story of frontiersman and fur trapper Stephen Meek. The Virginia native had emigrated to Oregon back in 1835, and many considered him to be well-associated with the region. He even made his living as a wagon trail guide. That’s probably why in 1845, a group of 1,200 migrant settlers making their way across Oregon’s high desert hired the then-unemployed Meek. Their goal? To find a safer alternative to a section of the Oregon Trail known as the Blue Mountains, where the murder of two Frenchmen had recently occurred. Meek led them southwest instead, through Oregon’s Malheur Mountains, an area of salty alkaline lakes, rocky hillsides, and dusty inhospitable terrain that also happened to be virgin territory for covered wagons. That’s because despite his good credentials, Meek was entirely unfamiliar with the territory. Nearly two-dozen of the settlers died from hunger, dehydration, and illness along what’s now known as Meek Cutoff, with another 25 exhausted emigrants succumbing to the hardships of their journey shortly after. (Anyone wanting a cinematic depiction of Meek and his route can turn to Meek’s Cutoff, a 2010 film starring Michelle Williams and directed by Kelly Reichardt.)

Then there’s Lassen Cutoff. Combined with the Applegate Trail from Nevada to Oregon, it provided immigrants an alternative to having to cross the Sierras, and risk the same fate as the Donner-Reed party, beginning in 1848. Rather than a traditional shortcut, however, the whole thing ended up being a really long detour in getting to California’s Gold Country, says Ken Johnston, a volunteer host for the California Trail advocacy group, Trails West. “It’s nicknamed the ‘Death Route,’” Johnston says, “because the Applegate/Lassen combination actually goes about 200 miles out of the way to avoid the dangers of the Sierras’ Donner Pass [a 7,056-foot-high mountain pass commemorating the ill-fated events that occurred there], which were by that time well known.” Instead it takes travelers across the Black Rock Desert (these days the setting for the annual Burning Man festival). “The playa is a barren stretch,” says Johnson, “and oxen and cattle died here by the hundreds.”

Ironically, it was this “Death Route” that probably saved the settlers’ lives, says Johnston, “because if they found themselves stuck on Donner Pass in the snow,” he says, “they likely would have died along with the livestock.” Instead, without oxen and cattle to do the pulling and carrying, many emigrants abandoned their wagons and left everything from clothing to furniture, and even liquor, behind.

That’s the thing about shortcuts: they can actually turn out to be quite beneficial, in the long run.

“Historically shortcuts are people pushing the envelope to try and develop quicker, more efficient ways to get somewhere,” Sweeten says. “Sometimes they are great successes, sometimes epic fails, but often they lay the groundworks for the paths we’re walking today.” They’re trailblazers by the very definition of the word.

In fact, the blazing of Meek’s Cutoff actually encouraged the forging of more wagon trails, and ultimately led to the settlement of eastern and central Oregon. As for the Donner-Reed Party, it was their forging of Hastings Cutoff’s Emigration Canyon portion that blazed a trail for Mormon leader Brigham Young. “[Through the work they had done], Young was able to get from present-day Omaha in April 1847 and into the Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847 [now Pioneer Day in Utah],” Sweeten says, “giving him and his followers enough time to plant crops and survive.”