The Man Who Walked Across Japan for Pizza Toast

Leather sofa seats, Mod bubble lights, elderly patrons smoking at the bar, and thick slices of pizza toast: These are the elements of a typical Japanese kissaten, or kissa coffee shop. Part bar, part restaurant, and part community center, these humble, Shōwa-era cafés serve tea, coffee, alcohol, and delightfully hybrid dishes such as pizza toast. Made of inch and a half thick slices of white bread topped with tomato sauce or ketchup, processed cheese, and whatever toppings the chef has on hand, this goey, crunchy comfort food is what American writer, photographer, and designer Craig Mod calls “a hug produced in a toaster oven.”

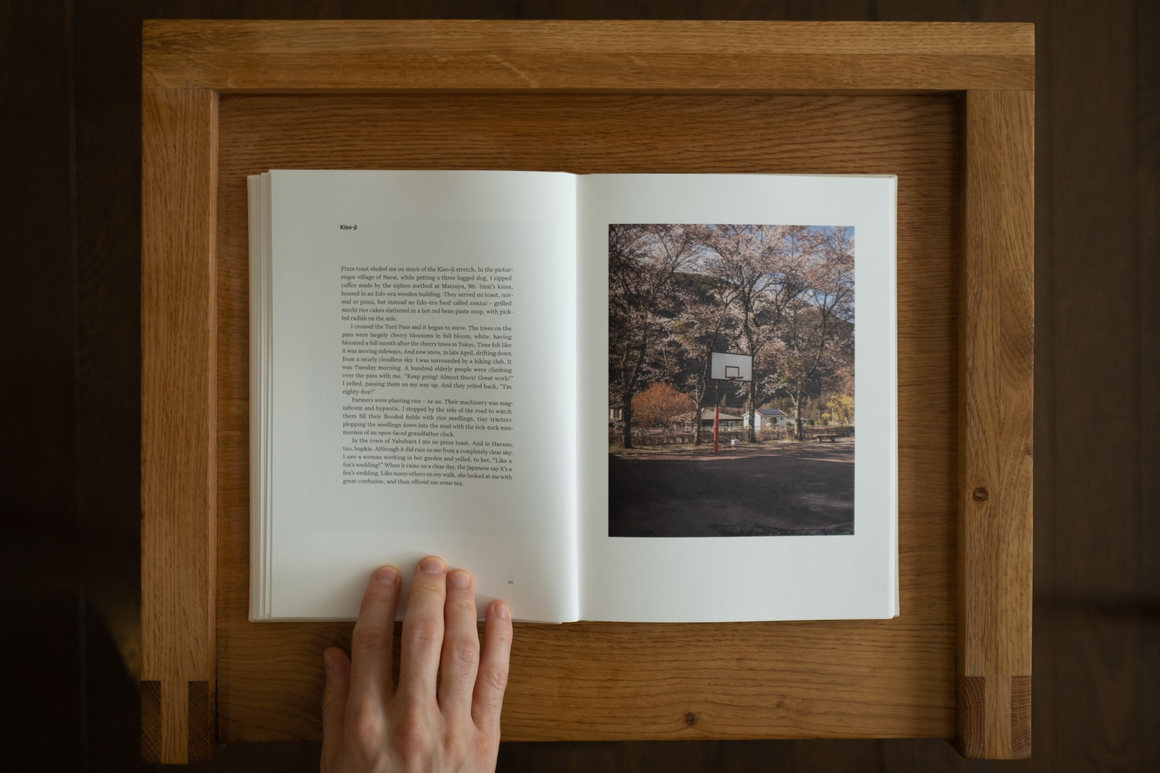

Mod pays tribute to pizza toast and these endearing eateries in his new book, Kissa by Kissa, which documents his 1,000-kilometer, 40-day walk across Japan in search of kissa and his favorite menu item. He follows the Nakasendō Route—a historic highway from Japan’s Edo period—from his home in Kamakura to Kyoto, often walking eight to 10 hours per day. In lushly detailed photographs and perceptive, punchy texts, we meet charming, octogenarian kissa owners, sample an array of pizza-toast styles, and witness fascinating, fading kissa culture.

Kissa emerged during the Western-infused rush of the postwar years, when American G.I.s and boatloads of wheat poured into Japan. The unexpected clash of cultures spawned an explosion of kissa throughout the country, each one a quirky mix of Western- and Japanese-style architecture, decor, and gastronomy. It’s hard to pinpoint the first kissa, but according to kissaten expert Toshiyuki Otake, their famous “morning set,” a matinal meal of coffee, salad, toast, and a hard-boiled egg, originated in the bustling port city of Nagoya. After the war, the city’s busy garment factories were too loud for managers’ meetings, so they moved them to the kissa, which now also serve Western-style dishes including waffles, omelets, and sandwiches.

But as pizza toast shows, kissa did not merely serve American food. The novel creations enjoyed in kissa and around the country included “Napolitan” spaghetti, made with bacon and ketchup, and “Hambāgu steak,” a meatloaf-like riff on the hamburger patty. While meat had long been an uncommon ingredient in Japan due to the influence of Buddhism, these dishes fit into the tradition of yōshoku, or Japanized forms of European dishes that proliferated in the 1800s. After the war, these meals became more affordable and accessible, and are still popular today.

When he first arrived in Japan nearly 20 years ago, Mod didn’t know what to eat. Having been brought up on uber-American grub such as Spaghetti-O’s and Fruit Roll Ups, traditional Japanese fare such as sushi or natto (fermented soybeans) seemed out of reach to Mod’s “extremely unsophisticated” palette. So kissa, Mod told me over a Zoom call, with their “American-style,” watered-down coffee and tabletop Tabasco bottles, became “a sort of bridge space for me between where I came from and Japan itself.” He’s in the middle of another long walk—this time along Japan’s ancient Tōkaidō Route—and as we spoke, he took a pitstop outside a 400-year old shop that sold Abekawa mochi (pounded rice sprinkled with grilled soybean flour and sugar).

Back when that shop was founded, the Nakasendō and Tōkaidō roads were trafficked by countless travelers, pilgrims, and elaborate imperial processions that moved at Mod’s pace. Today, Mod ambles along the shoulder of these paved highways, gradually traversing rice fields, suburban sprawl, and pachinko gambling parlors in search of kissa. Otake says that in its heyday, Japan had more than 150,000 kissa. Now, there are fewer than 70,000. Japan’s population is in decline, and most café owners are well beyond retirement age. Few have children or successors to take over.

Along with falling birth rates, Japan’s countryside faces depopulation as young people move to bigger cities. Despite the flight, most every small town in Japan has three things: a post office, a barber shop, and a kissa, which often serves as an essential gathering spot for those who’ve stayed behind. Many regulars use a book of tickets that the café keeps tacked up to the wall to pay for their coffee and morning sets.

As with any hyper-local spot, you’d be hard-pressed to find a foreigner in these places, and in one episode in the book, Mod recounts the literal record scratch and silence that takes hold as he, a young, backpacked, white Westerner, swings open the door to a roadside kissa packed with retired locals. Though the rest of his encounters are considerably warmer, Kissa by Kissa is full of moments like this, where Mod sees and reacts to people and things, and they see and react to him, too.

The result is that Mod’s pursuit of pizza toast spurs an unlikely series of exchanges filled with generosity and wonder. The kissa cafés are more than cozy rest points between long walks. Cumulatively, they form a constellation of meals and conversations, a sort of roving refuge in assorted brick, faux wood, and stucco iterations. Along the way, Mod documents a restaurant, a dish, and a lifestyle that’s slowly disappearing. And after a long day of walking, there’s nothing like pizza toast, which is, in Mod’s words, “a food that squeezes joy from very little.”