We Shouldn’t Have Been Surprised to Find a Sculpture of Hermes in a Sewer

Crews squelching their way through sewer systems in cities around the world sometimes find that they’re not alone. Their headlamps and flashlights occasionally fall across fellow creatures—rats scampering through the filth, or bugs, or even amorous amphibians. Some Victorian-era Londoners circulated stories about feral swine thriving down in the damp, and New York City residents have been talking about subterranean alligators for more than a century.

In mid-November 2020, crews working on a sewer project in Athens stumbled across a notably different figure. It wasn’t something slithering or scuttling, but a statue: a sculpted head of Hermes. The bearded face dates to the fourth or third century B.C., according to a statement from the Greek Ministry of Culture. Made in the style of the sculptor Alcamenes, the head had once been used as a street marker before finding its way into a drainage duct, where it was lodged into a wall, the AP reported. Many news outlets took the find as a chance to poke fun at the humble sewer (after all, it’s a long way from Mt. Olympus to an underground empire of waste). “Oh, how the mighty have fallen,” Hyperallergic quipped.

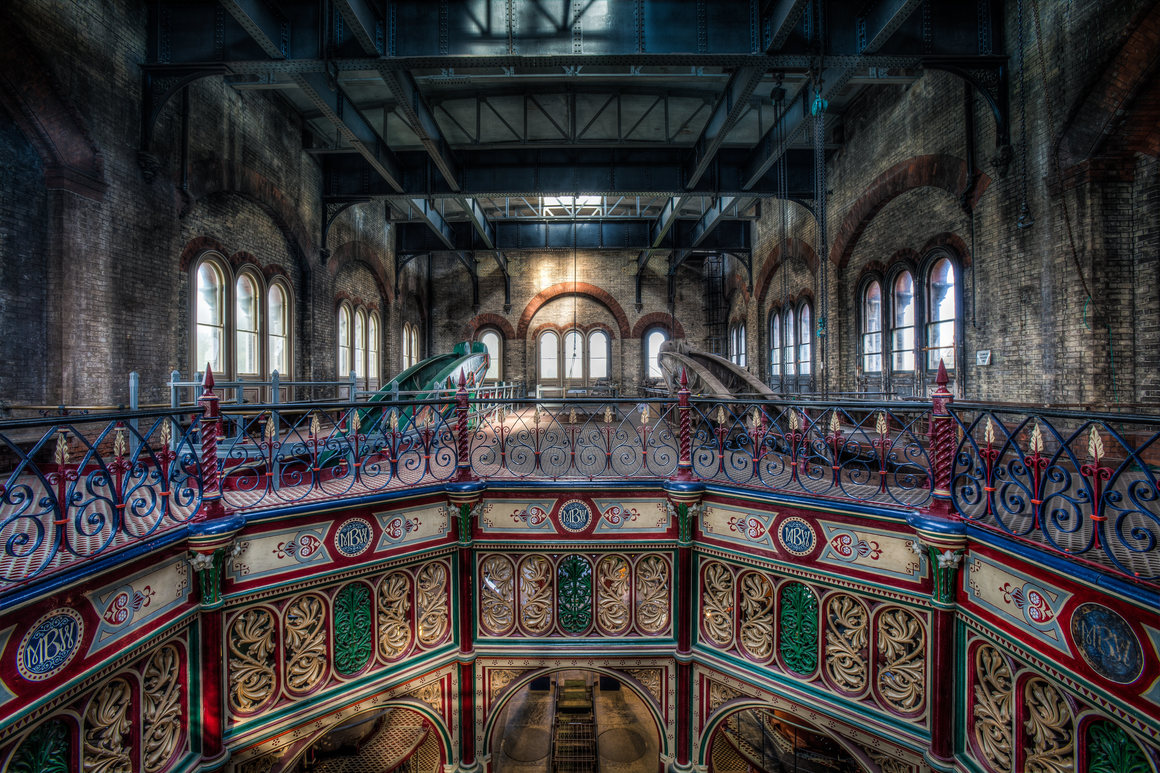

But Hermes’s presence underground shouldn’t have come as a surprise. While contemporary sewers are stuffed with all sorts of unsavory things—including massive, pipe-clogging fatbergs, used condoms, and, in one notable instance, a mess of waterlogged Yorkshire puddings—the sewers of yore were often considered to be among a city’s crowning glories. They were feats of engineering that generated civic pride, as reflected in elaborate drain covers or lavishly ornate pumping stations.

The first-century Bocca della Verità, or “Mouth of Truth,” is the enigmatic stone face that now greets visitors outside Rome’s Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin. The visage was likely once a massive drain cover “to give access to the sewers beneath the temple of Hercules,” writes historian Stephen Halliday in An Underground Guide to Sewers, or: Down, Through, & Out in Paris, London, New York &c. Eighteenth-century depictions of the massive Cloaca Maxima by Giovanni Battista Piranesi trumpeted the city’s grand, ancient system to such an extent that the mouth of the sewer became “a ‘must-see’ feature of the Grand Tour for young English gentlemen completing their education,” Halliday continues.

When London revamped its sewer system in the mid-1800s, Victorian-era officials housed the powerful new pumps—some affectionately named after members of the royal family—in stations full of colorful and elaborate ironwork. Crossness Pumping Station and Abbey Mills Pumping Station are a few spectacular examples. Decked with columns blooming with sculpted flowers and doors emblazoned with brass bouquets, the latter contains a hodgepodge of architectural influences and has been nicknamed the “cathedral of sewage.”

Today, the average sewage facility is far less visually stunning, but the entrances to some fetid furrows may still be works of art. Some 95 percent of Japan’s municipalities have manhole covers adorned with colorful community-specific artwork, which first popped up several decades ago, Alan Richarz has written for Atlas Obscura, “to help warm a skeptical rural population to the idea of the costly but necessary modernization of the country’s sewer system.” Sewer enthusiasts the world over—some of whom dub themselves “drainspotters”—document old, odd, or enchanting manhole covers. So it shouldn’t come as a huge shock that Hermes would have mingled with the mess.