Interview with Director Marco Porsia featuring Rodney Ascher

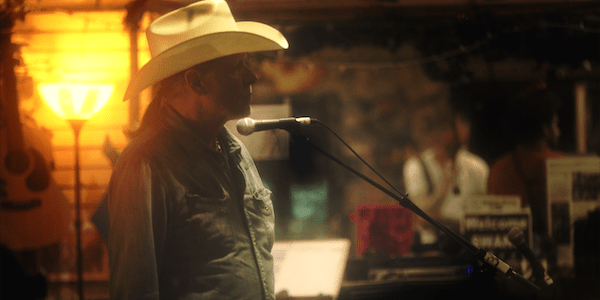

Over the last five years, director Marco Porsia had been accumulating a mass amount of footage from recording the concerts of venerated alt-rock group Swans. While gathering this treasure trove of material and getting to know frontman Michael Gira, Porsia set about to create a documentary on the revered music of Swans with the 2019 feature, Where Does a Body End?

With producer Rodney Ascher (Room 237, The Nightmare), Marco Porsia cultivated not only a Swans documentary, but the definitive Swans documentary. Thanks to some tête-à-têtes on Facebook Messenger with Ascher, as well as an inspired YouTube video (from yours truly) featuring the band’s song “New Mind,” Ascher was kind enough to put me in touch with Porsia, which led to this interview.

Due to a timing conflict, Rodney Ascher appears later in the interview to share his thoughts on the movie with us.

Alexander Miller for Film Inquiry: It’s evident that you, as director, are a fan of Swans and the work of Michael Gira. Do you feel like that was a significant part in realizing the story of the band as well as the leading forces behind it?

Marco Porsia: Yeah, I’ve always thought that I really believe that only someone who really knows the story of Swans could have made this film, but you know in a way yes, I’m a big fan since I was 11, just like so many people who has seen the films I feel like one of them I was in the position to make this, you could have asked Martin Scorsese to have made this stuff, but I feel like you need the insight to understand Swans, and Michael and the music it does come from a place of – I wanted to tell the story of the band that I had grown up with. Fan films always kind of have a bad reputation. They’re kind of cheaply made; you can tell like they were shot with a camcorder. But I think had the ability, and the skill to that was I looking to make, my own project. I had done a lot of work as an editor on many tv documentaries and directed music videos but nothing long-form like this.*

It feels like with a group like Swans, they are so singular a band that it’s so enigmatic and it feels like it’s a requirement to have to come from someone who truly understands the material and understands the music to make a comprehensive and cohesive narrative of the story and the music – like you said, a lot of fan-made or fan-inspired roc docs don’t have the best reputation, but you’ve put together a very terrific film in its execution both technically, and in approaching the subjects, it comes out terrific and it definitely feeds into the aesthetic of the movie it’s presented in a way that’s malleable for newcomers and diehards alike.

Marco Porsia: That was sort of my main goal, or challenge was to make something, to make it so that people who didn’t know Swans could go into the Michael Gira world of and get something out of it, and understand this band, and for fans, I knew that, I didn’t want to make something that was just for the fans, and just list the albums, in chronological order, there’s so much to the story, and I wanted to tell the story of Michael because Michael is Swans- I almost don’t see it as a music doc, it’s almost like a biopic. I wanted to almost hide the fact that I was a fan too – a lot of people who comment on the film can easily pick up on that I’m a fan.

Right, there’s a very visible presence of objectivity, which I think is one of the films many strong points, and you really give the subjects room to breathe and time to respond and discuss the music, especially Gira and Jarboe – while its evident that you’re definitely an admirer of the music it’s also very objective it feels very instinctive and evidence of a very well-made movie.

Marco Porsia: I started, you know I had an idea of how I wanted it to go, I started it in 2014, it was important to me that I started during that incarnation period, it was important to discuss so much and it was important to gather as much archive footage as I could. I know it was a daunting task just to tell that story that was 35 years long, but I started reaching out to people and everyone pretty much agreed to be a part of it, and started building this film from interviews and trying to hit all the story points I wanted. In the end, actually, Gira and Jarboe’s interviews were actually the last ones I did, and so once I had these, I pretty much had to reshape the whole film, and have Michaels’ viewpoints where I needed them.

What I really admired was the structure: you get the introduction to the humble beginnings, the NYC Music scene in the late 70’s early ’80s, the relationship with Thurston Moore and The Coachman as they were known then – they’d obviously be known as Sonic Youth. Then you get Michael Gira’s childhood, and the more personal story and it really shapes the movie. Was that intentional, or was it part of the process?

Marco Porsia: Yeah, I knew it was kind of tricky where to drop in Michael’s backstory. I wanted to have the material for the beginning of the band and then once you’re in tot the story then, go back going back to his childhood and the beginnings you kind of realize this is where he comes from, and his world view, so that was kind of tricky this is where Rodney helped me out with this also I would bounce of a lot of my cuts with him, and he was great in helping me shape this structure, I had so much material The rough cut was like 4 1/2 hours long.

While that would have been amazing too, yeah, I’d love to see that!

Marco Porsia: I tried to fit in as it was kind of a process of taking out what wasn’t necessary to the story and I’ve been an editor for many documentaries, so I’ve learned how to structurally tell a story, so I really wanted to make sure that Michael’s backstory was present in the film, and I wanted it in the right place of the film.

That’s another thing I wanted to ask you about: this must have been a pretty Herculean feat in editing, as I’m sure you had so much concert footage and archival footage to work from. Do you feel like you “found the film” in the editing process?

Marco Porsia: Yeah definitely I would say that – I had, it’s like a huge puzzle I was just building pieces, I knew I had the present-day Swans really well covered, I was going out touring with the band filming everything and documenting everything, doing interviews, but I was lacking was the material from the ’80s and ’90s. I had a lot of photos but Jarboe had alerted me to this box of tapes, of archive that had been long missing since they split up, I had reached out to Michael and he didn’t know what this box of videos tapes where had been for like a whole year, I had been editing films and one he wrote and said “Hey Marco, I think I found what you were looking for,” and I drove down to New York and got this big box of like 100 VHS tapes that had been fan footage from concerts from the early 80s to the 90s, behind-the-scenes stuff, it was like the motherlode, like an archeological discovery and I knew that I could now tell the story of the early period as well along with all the interviews – and as I kept editing I thought that “Yes, I could tell the complete story throughout.”

Yeah, because you were saying you had so much footage from the 2014 era forward, and that must have been quite the discovery in tying the entire narrative together. Another thing I thought was interesting was that I wanted to ask about Rodney Ascher’s presence and involvement. His work in Room 237 and The Nightmare is very much about artists and their work, but how people interact with that? Was that an influence on your directing style?

Marco Porsia: Um, no, not in that way necessarily, but we’ve been friends going back to university, and he’s done so much brilliant work, and I admire what he did with all of his films. So he was such a huge support throughout when I was going crazy with all the logistical things, well everything you know? He’s been through it, so he was invaluable in helping me make the film.

Excellent, there’s something really wild, and I was kind of talking to Rodney [Ascher] about this off-mic – it’s kind of this reaction people have when you ask them about Swans, no-one says “Oh, I like their early stuff” or “I like a couple of songs” – you hear words like “sacramental” or “shamanistic.” It sounds like something you’d hear in a religious studies class; was that at all kind of intimate in shaping the documentary at all in that Swans is just so larger than life in so many ways?

Marco Porsia: Yeah, I was kind of finding this out as I went along too. As I was doing the interviews, I would get this incredible response, you know? From people like Amanda Palmer and Devendra Banhart stuff I wasn’t expecting if these musicians aware, you know, saying this about the band I was really, kind of in awe of what it brought out in people and other musicians and fellow band members, it’s something that, I guess I was still in my own bubble, I was a fan but I know people who are fans, but that was about it, I kind of discover all of this while I was making the film about the influence of the band and the reach, when I would go to film shows, and you see all these young kids and the front of you know losing their minds, it was just amazing stuff to watch, often I would just film the crowd, just completely in this transfixed state, for me seeing this stuff i was very privilege even to witness all this, so that was my role, was really to document everything that I could. I didn’t want to miss one thing, at the shows, I would try to look for something that was not going on onstage. I also didn’t just want to have concert footage; that’s why I wanted to get as much variety of stuff. I’d ask Michael to go to the gallery with me, (opening scenes) for the Richard Serra exhibit, you know, filming him in the desert and it wasn’t easy because he doesn’t like to be filmed, but it was important to that I get all these, to create something that’s more than just a music doc, also I used my super 8 camera, and shot a lot of film to give it a certain quality that I think, fit the aesthetic of Michael.

Yeah, I did notice that it looks like there’s different film stocks and pivoting between digital or and 8 or 16mm?

Marco Porsia: Right.

Yeah, it contributes to the span of time that the film covers, and I guess in speaking to that, the structure what I found really fascinating, once Jarboe joins the group, you kind of go from album to album, and I thought that was really important because back then you didn’t have digital streaming and all that and that’s how you interacted with music, was that you didn’t; t know what was going to go on until you heard their next album and with someone like Swans their albums are very conceptual it’s an important thing to focus on, was that a more intentional decision on your part or was it kind of part of the documentary?

Marco Porsia: Yeah it was intentional to cover those. Because each of those albums are so different, I could always explore one, and when Jarboe came into the band, it just went from every album had its own influence. So those were really important to capture individually, obviously Children of God, Greed, I also was a teenager during the time these records were released so I sort of lived the excitement of those records in the moment. And I witnessed how when The Burning World came out it was this kind of big downturn, you know, not well received? And to me, that was such a powerful story that I tried to bring out. Trying to claw your way out and start again and again, make every album after that, was just more and more challenging, and pushing and pushing you know? For that period, I tried the albums to kind of be their own thing, but then when they reformed, it was more about the sound, so I don’t really talk about the albums themselves (after 2011 reformation). It’s more about the viewer discovering this era on their own.

I especially enjoyed the section on the burning world because it’s important to note when an artist falters, but when they experience falling out of vogue, say the. I don’t want to say the commercial mainstream, but when they make a creative misstep, because then it motivates an almost more motivates a creative renaissance, like after David Lynch failure with Dune, “I can only go up from here”, and I feel like that’s also the attitude that came from around The Burning World, if it hadn’t been for this diversion we wouldn’t have all these other incredible works that came afterward.

Marco Porsia: Exactly, Michael is very hard on The Burning World, but for so many people, so many fans’ favorite album, but it was seen as such a failure. it was in a way, telling this story, there needed to be something to climb up, then you go down, then again you rise again, it happened a lot with Swans’ trajectory I didn’t get into all of these ups and downs, but that was definitely the main one.

Yeah, because the other interesting thing is that they, as a band, really eschewed genre; they are frequently associated with punk rock movement, things like that, but it’s evident that they are very much their own thing, but it’s interesting that they were courting or flirting the music mainstream, and I think that’s more evidence that they are very much their own beast and that’s the way it’s going to be – you know what I mean like it’s this “take it or leave it” mentality you get from the music and Gira, and in so many ways it’s the path of the movie as well, it’s the self-styled artist as they work,

Marco Porsia: Yeah Michael is a true artist and that was maybe the film I was trying to make, about the life of an artist that is just, completely uncompromising, and just sticks to his vision no matter what, and it’s something that I would definitely want to bring out in the film and there were some threads that I wanted to make sure, that I thought were really important, of Michael life as an artist, to me the films is also part love story with Jarboe, her influence all over the music and the trajectory of the band, her importance was beyond words, and then it’s also a friendship story with Thurston and I really thought was very powerful, you know to have these two people who ended up, in 1982 they didn’t know would become these legendary bands, but I wouldn’t definitely capture their friendship and the beginnings because it was helpful, when I have to describe the films to someone who doesn’t know Swans its like you know “do you know Sonic Youth?” and it changes, well, you know, everyone knows Sonic Youth, and there’s this parallel between of the two bands as they got more and more powerful. You have this one band Sonic Youth, becoming world-famous, and going on a major label, selling hundreds of thousands of records, at the same time that Swans was putting out The Burning World, which was a disaster in terms of the major label collapsing just as the record came out. They didn’t promote it very much.. You know there’s definitely something that obviously hurt Michael and it was this really painful, so then I wanted also to capture their reunion years later and that was really important for the story of the film.

And another thing that really stuck out to me, and I think it’s also contained the band in a unique light, is the presence of Jarboe and the relationship between she and Gira, but what I really liked is that in the film, she has a lot of time to express herself and her relationship not just with Michael but with the band also the punk/hardcore scene, especially at that time was often viewed as kind of a boys club, and then seeing the story of the group from a women’s perspective I think really opens up the story and opens up the film; is that something that stuck out to you?

Marco Porsia: Yeah, as an outsider looking in, I always thought that Jarboe’s presence was so important in shaping Michael’s vision and then the music, that was also another huge challenge was to put Jarboe in the film, and put her, and show her importance in the band and in the evolution of the band because, because a lot of people don’t know, or maybe don’t realize that, and yeah she’s a huge part of keeping the band going through all these hardships. You could do a film on Jarboe, she’s such an incredible presence, and light, you know, like one of the interviews, she’s like “the light to Michael is darkness,” and it was really important to get her side of the story and show her importance in the band, and everything that went along with, the breakup, going through all that with Michael, I was more worried about Jarboe’s than Michael’s sort of reactions to interviewing him, and in fact, I did two interviews with Jarboe. But, she was a huge help, and she also wanted people to know, you know, it’s your life story, for her as well, so she was behind the project and really helped with a lot.

It’s really wild, and I love the scene where she refers to going on stage in the earlier phase of the band, where she refers to herself as being like a “sacrificial lamb,” since people are expecting this hard-driving “moshing” music. Then you have this very expressive woman singing, and it’s again a testament to how unique and what driving-force Swans are; I also found the relationship between Sonic Youth was completely new to me. I had known there were some parallels, but the friendship between Thruston and the group was very endearing, and seeing the reunion show was so cool (both laugh).

Marco Porsia: Yeah, when I found that they were going to play together, I immediately bought a plane ticket to london, I didn’t care how much, I put it on the credit card at the moment –a lot of times the film was kind of shaped during the making of it, even during the interviews Michael started talking about how, during the Greed era he was watching a lot of whats the name, the televangelist, blanking on the name, the famous one, and you’ll have to insert his name, (Laughs) when I heard that as I was doing the interview, I immediately thought “that makes perfect sense” so I immediately wanted to illustrate that point and found some archive, and having that old archive of the live performances, it’s incredible to see how Michael is just like a preacher on stage, screaming to the audience, especially during the Children of God phase, a lot of times that happened I would just kind of go in that direction, and where I thought there was something there, in the story, even if it was stuff I didn’t know about.

I definitely wanted to touch on that televangelist thing–it’s fascinating; you usually equate with punk, metal, or industrial there’s usually this combative attitude toward organized religions or something like that, and what I thought was so fascinating is that Gira’s reaction is more curious, being so enamored with what this guy was doing, instead of fighting it he almost embraced it, and again like you said you can see it in his stage presence, especially during the Children of God era, and it carries through even into the later shows where he’s conducting this immersive wall of noise at the live shows.

Marco Porsia: Yeah, I’ve been. I always saw him do that, but I didn’t realize why he was doing it, you know? It was kind of like the mad conductor, and then it’s been many periods. At any period, Michael would absorb a lot of things, and later he would, later he would be influenced by Buddhism, and that comes through there, and it’s not that he’s a Buddhist, but he really goes into that world and kind of extrapolates that in his singing.

Kind of channeling the ritualistic nature of it?

Marco Porsia: Yeah

It’s a fascinating perspective, again, to speak on influences and when he (Gira) talks about going off to Europe in his early years and both surprising and interesting like you have some blue inspirations. You know, being in Europe and seeing Soft Machine, Frank Zappa, Procol Harum stuff like that, is interesting because you can see the artistic tethers to these groups. Still, it’s wild seeing these tendrils going from the end of the spectrum to the other and seeing how they shape the almost indescribable style of music.

Marco Porsia: Yeah and I kind of witnessed this, in filming the band when they were recording, glowing man, where, just watching him in the studio was really fascinating because he would instantly, he new exactly what he wanted, he just knew, he was really intent, but at the same time, like John Congleton says, “he’s not a musician per se”, he hears, and he’s really good at bringing things out of his players, and getting this incredible sound and feel, that to me is, and has always been whats there’s something about the Swans aesthetic and sound that it obviously it hit me at an early age, and really kept going, and I would say that, I think Paul Wallfisch mentions this, “there’s two bands in the world that have arrived in 40 years and are still relevant vital music” you know, like Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Einstürzende Neubauten, these are all bands that people really connect to on a really deep level, and, yeah, I’m glad the other people have felt the same – it’s like when you’re young you think you’re the only person thats into this band, then you find that there’s someone else, then someone else, and in a way, open up a whole world even for myself that i didn’t know about. Many filmgoers around the world have thanked me for making this film and that’s been the biggest reward of all.

I think it’s one of these things that where you connect tow something on such a deep level it feels like hundreds of thousand because the response to it so enthusiastic like you said, it felt like it was your thing, then you find out your thing many other people’s things, and like musicians Nick Cave, Einstürzende Neubauten there’s just this otherness to them, and just like Swans they are very self-styled and self-guided, it was really cool seeing Blixa Bargeld -as a long time fan of Einstürzende Neubauten too it was really cool to see, and it wasn’t a shock to see that they’re sympatico, Swans and Neubauten.

Marco Porsia: Yeah I was really lucky that I got Blixa, because I think that Blixa did it mainly as a gesture and appreciation of Michael, so he agreed to do it, and that was one of the interviews that I didn’t do, but it was probably better that way, because I probably would have totally scared….

[Both Laugh]

Marco Porsia: So yeah, people like that really helped cement the film, even though he’s not in for that long. it’s what he said that’s really important. I tried to get Nick Cave, Henry Rollins, Jello Biafra, Iggy Pop, and other people, but it’s almost impossible to get everyone you want to.

Yeah, the immensity of how many people artists can touch; it can be really daunting and hard to get your grasp on. But the subjects that you have interviewed for the film I think, paint a very vivid and cohesive portrait (moves cat), and its endlessly fascinating. You get a lot of studio footage of Gira and the band at their most recent iteration, and it channels that feeling of being in the studio, it’s a very unique headspace to be in, and you get that. Was it tense at all being around for those?

Marco Porsia: Yeah, that’s actually another thing I really needed to capture. By then, they had announced that it was the final tour, so it was part of the story, and I was able to go down, I asked Michael if I could film for a few days, they were there for a week; I know I needed to get some material. And being a musician myself, there’s lots of stuff that happens in rehearsals; I tried to make myself really small and not get in the way, you know? No one wants to be filmed when they’re rehearsing. Yeah, it was really tense at times, and there’s that big explosion between Michael and Chris Pravdica, and in a way, for the film, I was lucky that that happened, but it was very tense. I was filming outside, and I could tell things weren’t going well, and of course, Michael is very demanding of the band, and I was filming from outside the room, and this incident happened, and Chris stormed out, so I basically took off! I came back like half an hour later, and then I realized, “oh my god,” I had the GoPro running for some of the rehearsal. You know, I started thinking, “maybe I actually captured that” because when I was outside, then when I checked and I actually had that on there and I couldn’t believe it! It’s something that really helps tell the way Michael works, and the little private, intimate moments I think really help take you inside as well, just letting these things play out. Because they are such a tight knight band they had become, it’s interesting to juxtapose a scene like that with a scene like the hugs they give each other at the shows, so that to me, makes the fight even more warming, it’s always strong when you seem them hug, it’s like a resolve.

There’s some emotional response to things like that is the result of the way people interact with each one another; I mean, you’re not going to react that way to someone you don’t have a connection with, and it was very endearing to see the pre-show warm-up seeing the band give one another hugs, and a testament to the artistic commitment on the bands behalf, and it was a really smart juxtaposition, it could have very easily slid easily into the “Gira show,” but you get a feeling for Swans as a band, and that’s huge.

Marco Porsia: Even the fight itself was kind of like Abbot and Costello, “play lower, I said play lower like you did yesterday” it was just, it was the times like that were very hard on the players, and they would go on these tangents, and Michael gets so stubborn. And a lot of the band probably ready to end it, just because they had so much abuse, in a way, but they love each other anyway, so I was glad I was there, again, that was the main thing I needed to capture everything I could because it was ending, it was this other end, it’s this other parallel, in 97, the band was growing and growing, and he just killed it, then 20 years later, he does the exact same thing, the band was riding this wave of popularity, and then he decides to end it.

I think it’s really interesting, like you were saying before, not having as much traditional musical training, so when you say playing it higher on the neck doesn’t necessarily always mean you’re playing something “higher,” and that’s just the kind of thing that would make a musician a little crazy -(both laugh) and they definitely relay some of that in some of the interviews with the bandmates, it definitely paints a very vivid and candid portrait of the artistic process- I think it’s one of those things, where yeah, he pulled the plug on it in 97. He’s pulling the plug on it now. Do you get the feeling that as an artist, there’s such drive, do you think that there’s going to be more music from Gira?

Marco Porsia: I definitely believe that he’s kind of like a Bowie, and where they can’t not make something, so, like Kristoff says until they’re six feet underground. Just like the last album, Leaving Meaning that he put out, is just incredible, a whole new direction; I thought it’s one of the best albums yet, I definitely think he’ll keep going, especially in these times I think he’ll keep doing it.

It’s interesting too that you have so many bands that maybe their heyday was in the ’60s 70’s ’80s 90’s or what have you, then they break up, then fan culture develops a cult, then they come back; everyone’s a few years later, everyone got sober, and they have a reunion tour, and then it sucks and doesn’t yield very much. (Laughs) however, with Swans it’s like they came back stronger and better than ever. It was really compelling to see, and seeing the footage, and the concert was fascinating because there’s enough time, you give the concerts enough time to breathe, and it’s really important it’s like the performance of The Glowing Man (meant to say “Cloud of Knowing”) and it’s something like a 30-minute song, and…

Marco Porsia: Yeah, it was Cloud of Unknowing it grew to be like 50 minutes, in one of the final shows in NY toward the end. I wanted to keep it as long as I could; I wish I could have opened up all the other performances, but it would have grown into 3-4 hours; I’m hoping that Michael will want to release all the full performances, a lot of the songs that I have on this film and it was a struggle balancing and trying to find, and when to let the music and interviews balance each other out.

Because I do love that, it was almost like the captions wold read “the song has taken a life of its own where now it’s 50-minutes long, and I’m like “please let it play, he can’t cut it off” and you let it go for a while which is great because it whets the palette, after that, I’ve been going on another crash course of their music – I guess that answers another one of my questions and that’s if you’ll be able to, or hope to, be able to cut, and release some more concert footage?

Marco Porsia: When I did my first cut, it was 4/12 hours; there was a lot of good material that I had to sacrifice, but I wanted it out still because there’s so much work that’s put into that. But for the Blu-Ray edition, I’ve got a whole other disc of bonus scenes that is 2/1/2 hours long of extra material that didn’t make it into the film, and so I have that, but then there are another two hours of performances that I wanted to include, but it was too much material but I had to hold back – but I think that I’ll talk with Michael and maybe put it out as its own thing.

Yeah, I mean, the potential and interest is definitely there.

Marco Porsia: Yeah, yeah, people want to see that, and I think that there will be; every era is documented really, really well, so I really hope that it will come out, but I’ve got the bonus scenes. I’ll send you a link to you.

That’d be awesome.

Marco Porsia: If you want to look at that and mention it because it’s almost like another film.

I had a feeling there’s a lot of footage, both archival and concert tats on the cutting room floor, as they say, that’s definitely worth digging into – there’s another thread of aesthetic consistency within the film, even down to the font and captions that you use that’s similar to that of the albums and the cover images. I can picture myself in the record store and passing through the Swans section and seeing a copy of “Where Does a Body End” with the artwork that the movie has like it was another Swans disc.

Marco Porsia: I mean, it wasn’t even an option; I had to use the font and the Helvetic outline, which was used to Public Castration and Greed, which I’ve always been; you fall in love with those album covers, that typography, it’s so strong, so I wanted to do something that imitated that, and that looks like Swans, I wanted the Title “Where does a Body End” to have like a strip of black, kind of wrecking the name, like a black line over the eyes, like when you don’t want to be recognized. I wanted to do a mix of those fonts, and I was really glad that I got Paul White, who was the guy who helped Michael do all those designs for Greed covers and Children of God. He’s in one of the bonus scenes where I talk about all the artwork for that period.

Again I thought that was excellent that that was referenced in the film as well; because it’s another piece in the puzzle that is Swans, the album covers, and layout, it’s such a distinctive feature, and it feeds into the image and sound they cultivated like I was saying you’d be flipping through the discs at the record store was the coolest thing. You’d see all these very evocative images, of courses and teeth and money symbols and they jump right out at you.

Marco Porsia: Yeah, and the artwork was done by this great artist that I met in Europe Hrvoje Karalic had done some separate Swans posters – and his artwork looks just perfect for this kind of universal eye or something that would sort of draw you in.

Yeah, this like “watcher’ feeling is very evocative, and it ropes you into this larger ethereal conversation that is the entry of Swans very cool stuff, definitely.

Marco Porsia: Thanks

ENT. Rodney Ascher

It was funny I was telling Marco earlier about the video I made with the New Mind song, not knowing you had produced the documentary on Swans, and then you turned me over to Marco and here we are…

Rodney Ascher: It’s weird how everything seems to be connected these days..

Serendipitous, yeah.

Marco Porsia: Maybe it’s a “glitch in The Matrix?” I told Alex how valuable you were in the whole process with all your knowledge, anything, everything you were like a guardian angel (laughs).

Rodney Ascher: (laughs) I just tried to watch every cut as if I had never seen it before, and to forget what I knew about the process or even Swans, and that’s always the trick, in an edit, —forgetting everything that’s not in the movie, and to try and watch it fresh, and imagine, how someone who isn’t you would get it, when they see it the first time.

You almost wish there was a delete button you could hit, so it could all be new again?

Rodney Ascher: Yeah, well, Walter Murch had an interesting thing to say, that he never wanted to visit the set of a movie he was editing because he didn’t want to know what was just off frame.

Right.

Rodney Ascher: And he didn’t want to know how difficult any shot was to get because that didn’t make it a better choice to use in the movie.

I can see how that could make the editing process a little more tortuous in the editing room.

Rodney Ascher: So that was a lot of his process, only seeing what’s in the film.

And Walter Murch is, as we know it, is no slouch to the world of editing…[Laughs] Definitely, this is very terrific. It’s definitely rekindled my long-standing love affair with the group – one other thing I wanted to ask, what was one of the first interactions you had had with the group or Swans’ music?

Rodney Ascher: Me personally?

Either….both?

Rodney Ascher: I wouldn’t be surprised if Marco didn’t turn me on to them, we went to school together; Marco was a DJ at the college station, and, I was sort of a wannabe who would hang out and try to find excuses to thumb through the records, or to try to turn people onto Marco’s show, or another friend of ours, Syd – so that was a time, we were turned on to a tremendous amount of music and being able to have the resources of a college alt-rock station, whose record collection, you know it was, it is, the closest we were able to get to Spotify, back in the 20th century.

Right, back when college radio and all that was where you discovered everything, that’s where it all went down, man.

Marco Porsia: Back then, you had your; I think if I introduced Rodney to Swans, maybe? I can’t remember, but Rodney Introduced me to Foetus, Butthole Surfers; we kind of, everyone went to Miami, we stuck out quite a bit out there, so our love of music is really what saved us, or what bonded us.

Rodney Ascher: And the scene was pretty small, so a lot of us are still pretty close, Syd, who was part of that time and place supervised all the animation of my new film, so those days have left a huge imprint on what me and Marco and a couple of others have done.

It’s really wild, and Rodney, I know we’ve discussed music off-mic, and stuff like that, and it’s almost like Swans is like a “musicians group” it’s kind of a low-key passcode, like if someone tells you they’re a Swans fan, it usually means they’re pretty cool.

Rodney Ascher: And we were old enough to get in early, like Greed I think was the record that was first on my radar, and that’s a more interesting transitionary one, it’s a little more accessible than Filth, but you can go back to Filth and see where it came from and then you’re on board for the ride as it evolved into Children of God and beyond.

And what I think is so fascinated is that if coming out at this time s that you have the now wave scene going on, with DNA, Glenn Branca and Theoretical Girls, you know this specific subset and that what’s interesting that I had actually forgotten when watching the film is that you have Circus Mort and like revisiting Circus Mort and even in this very specific subset what they’re doing back then is so different from what the peripheral genre was.

Rodney Ascher: That scene That time and place so much music episodes out of it, if you spend a lot of time talking about it, Sonic Youth a sort of brothers in Arms, and Madonna came out at that time too, and I always wanted to make more on that because that contrast is so unbelievable–though those first sort of underground disco records are not necessarily “another planet” from that scene…

Oh yeah, the CBGB stands for “Country, Bluegrass, and Blues” and I think that was the stipulation that you had to play your own music, and they didn’t want covers and cover bands. Which is when you have Television and Talking Heads coming up – and you had the owner of CBGB saying they didn’t sound very good, but he went along with it, because he saw that these guys had a pretty devoted following, I mean when in Rome, right?

Marco Porsia: That’s the reason why Michael left LA for New York because of that whole No-Wave scene, he was so into that, and by the time that he got there, they never even fit into that scene.

Even in such a unique subset, Gira and Swans are almost bigger than, you really can’t eschew genre and categorization, and that’s why they’re such a topic of fascination.

Rodney Ascher: And I think a nice thing about Marco’s movie too is that they’re a really difficult band for people to get into today because there are so many records to go through, so many changes, and that a random needle drop is not necessarily going to be representative. But, the movie does this amazing job of taking us through the different stages, and different audience members can choose which porridge is too hot or too cold.

That was cool too, we’re talking about that’s how you interacted with a favorite band or musicians. It was on an album-to-album basis; you didn’t have them dropping singles on streaming platforms, you had to wait till the new album came out and buy it then go home and listened to it, and with a group like Swans is that they’re very musical and the albums are very conceptual, it’s a very distinctive hallmark to track and follow. It was actually funny, my introduction to Swans – used copy of Soundtracks for the blind record store, a friend of mine, these two brothers were these terrific musicians so it got to point where anything they recommended was like the gospel. They said “there’s a used copy of Swans Soundtracks for the Blind” and “just buy it”, and I did and they were almost upset because it’s like I started from the best, like “You started with their best! Anything else is going to pale” and it’s funny I worked my way back through their discography – and from my point of view that was the was the best way to do it, and then everyone else I talked to was like “no, that was the worst way to do it, you should have started with Filth or something like that.”

Rodney Ascher: There’s something about starting in the middle, Anton my ten-year-old, really in The Simpsons, and he got into the middle/new ones. Since then, when we got Disney plus, he kind of went through it and he found that the season where they went digital/HD and it was season 20, then went all the way to the end. Then went to the beginning and was able to notice every single important thing as it happens; “this is the first appearance of Krusty, this is when -Flanders’ wife dies, etc.” he was able to recognize all the significant moments and their reverberations downstream.

Which is cool, your contextual barometer kind of gets reset in a way, that you said he can spot and pick all these hallmarks and large events that go, which is such a cool way to go about it.

Rodney Ascher: Also, this movie took a very long time to cut, I don’t know how many versions Marco made; I probably watched about ten of them. And there are all sorts of questions “is the beginning of this movie when Michael Gira is born? Where is the beginning of this movie? ” I was lobbying for the beginning of the movie being the 1997 breakup myself but we start now in the present day and that makes sense. But yeah, in documentaries, first, you have all the facts or the pieces, and then you decide what the puzzle is going to look like.

What I liked about the structure is that you get the introduction of the band, then you get Gira’s introduction, and then it kind of puts it on this equal footing, and that it established that this is the Band’s story and that this is Gira’s story as well, and it could have very easily turned into “the Gira show” but it’s very much the Swans show.

Rodney Ascher: There’s something really interesting is that it gets very performance heavy in the last third, the live stuff Marco shot on their final tour, the movie, is over 240, the extended version, so you get two hours of getting to know these guys then you get to see them play. And you get this ugly duckling thing like quality about them, sure they can talk and explain what they’re doing with words, but that’s not their native element. What they really do is play. And then you see them really, fully actualize when they’re on stage playing, as opposed to what you knew of them earlier from talking; And you need that length to get to that point.

Marco Porsia: It’s true, it’s a good point that Rodney made, because it was one of the struggles, how to begin the film. We tried different ways, starting in 1997 is one way, then the backstory, that was one of the challenges, was how to get into the story. But yeah, everyone has a different entry point with Swans, and that affects our vision of the band – the first part is very historical, obviously because of the time, you know forty years. At the present time, I was thinking that the stuff I shot between 2010-17 is already archive! That’s already history and the movie I was filing, the present, but it’s already archived…

It seems so recent, right?

Rodney Ascher: And they’ve already made a new album since the film stopped shooting.

Which is terrific I also think that if this were a 90 minute or 100-minute movie, I wouldn’t trust it in a way. I mean, of course, a Swan’s doc, or the definitive Swans doc, as I feel this is has to be almost three hours long, I mean, how else do you engage with such an enigmatic and ethereal force of music?

Rodney Ascher: Which is funny. When I was watching different cuts of this movie; the first time the movie worked for me is when it was four hours long. It was shorter for a long time; then it went up to four, then I thought, “that’s fine, release it like this” you know, that’s an insanely long movie, but it’s like going to one of their shows, you know? More sober heads prevailed, but it had to come down from there. When it was shorter in its earliest cuts, it hadn’t yet, come together.

Marco Porsia: It was the length, I could have pushed it to over three hours logistically, technically, gets to be a mess with the length, size of files, and everything, but two and a half is pretty much the length they would play live, so I wanted that to be the equivalent of being at a live Swans show.

The parallel of the music and the film – it’s a perfect marriage of content for fans and content for much more curious newcomers alike, but also, thanks to home video and blu ray an everything we can have to bonus stuff for the completionist to gnaw on, (laughs) and drool over because Id be all over that and I’m sure many other people I know as well, the reactions to this documentary of people I know who enjoy the group, they always have this same reaction, ethereal, the ritualistic experience of this band and there’s nothing quite like it, and I’m eager to pass this along to all those many people who admire the band so much.

Marco Porsia: Yeah, that’s Great, thanks Alex!

Thank you, you guys are terrific!

Film Inquiry would like to thank Marco Porsia and Rodney Ascher for speaking with us.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!