GOODBYE, DRAGON INN: Long Live The Magic Of Moviegoing

Throughout this pandemic year, it is safe to say that the activity I miss the most is going to the movies. The shared excitement as the lights finally go down and the anticipated film begins, the moments of communal shock and awe as the audience collectively gasps over a plot twist or cheers a heroic moment, and the gorgeously crafted images blown up so big they could swallow you up and remove you from the real world, even if only for a moment… many movie lovers compare going to the movies to going to church, but this lapsed Catholic would argue that doesn’t do the unique thrills of the theatergoing experience justice.

In 2003, Taiwanese auteur Tsai Ming-liang released his masterful ode to the magic of movie theaters, Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Like his quarantine-focused 1998 musical The Hole, which was re-released in virtual cinemas this year, it’s hard to think of a better time to revisit Goodbye, Dragon Inn than at the close of a year that has threatened to destroy the theatergoing experience once and for all. And while watching Goodbye, Dragon Inn’s new 4K restoration on your laptop, instead of gazing up at it on a massive screen in the dark, surrounded by fellow film lovers, feels wrong, the act of doing so also reminds us exactly what we’re missing.

The Last Picture Show

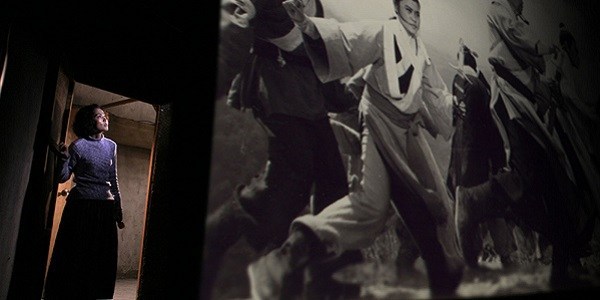

Goodbye, Dragon Inn takes place over the course of the final evening of operation of a run-down yet still regal Taipei movie theater. A handful of scattered audience members have curled up in the cavernous auditorium — truly, a movie palace if there ever was one — amid its rich red plush seats to watch King Hu‘s 1967 wuxia classic Dragon Inn. Despite one woman (Tsai regular Yang Kuei-mei) who seems to be going out of her way to be as annoying as possible, chomping loudly on peanuts while resting her bare feet on the back of the seat in front of her, many of the small motley crew in the audience are enraptured by the movie. This includes two of the original stars of Dragon Inn, Shih Chun and Miao Tien (the latter a frequent Tsai collaborator), who watch their younger selves battle it out on screen with tears in their eyes for days gone by. As Shih Chun later notes, wistfully, “No one goes to the movies anymore, and no one remembers us anymore.”

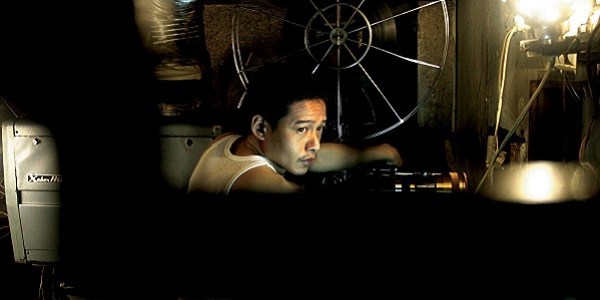

Outside the auditorium, with the sound of pouring rain battering the roof and splattering into buckets courtesy of the leaking ceiling, the theater manager (another Tsai favorite, Chen Shiang-chyi) struggles to carry out a series of chores with an iron brace on one leg, limping and hobbling up and down steep stairs and winding corridors. Her main objective? To track down the itinerant projectionist (Tsai’s main muse, Lee Kang-sheng) and present him with half a steamed bun for a snack. Meanwhile, a Japanese tourist (Mitamura Kiyonobu) strolls the darkened halls and hidden backrooms in search of a homosexual encounter, smoking a cigarette while sidling past other men on the prowl for the same thing. However, when he finally tracks down the man he wants, he is not only brushed off but informed that the cinema is haunted.

(Slow) Cinema Paradiso

Befitting a film that mostly takes place inside a movie theater auditorium, there is very little dialogue in Goodbye, Dragon Inn (apart from what is spoken by the characters in the film they are watching, of course). When the Japanese tourist is informed that the theater is haunted, at approximately the halfway mark of the film, I found myself struggling to remember if anyone had spoken out loud before then — I don’t believe they had. Yet because this is a film by Tsai, renowned for his minimalist storytelling and apt use of imagery and ambient sound to convey inner emotion, one doesn’t need words to understand the hunger for human connection at the heart of Goodbye, Dragon Inn — not to mention, at the heart of moviegoing.

The story arcs in Goodbye, Dragon Inn are lightly drawn, but that doesn’t make them any less moving. Using long, static but elegantly composed shots, Tsai and cinematographer Liao Pen-jung capture the individual melancholy of each character with incredible beauty. When the manager drags herself up the stairs to the projectionist booth only to find it empty, and her earlier offering of the steamed bun untouched, she can do nothing but collapse on the stairs in disappointment and exhaustion. Accompanied by only the rattle of the projector and the muffled soundtrack of the movie in the background, we stay with her for a long moment as she contemplates what to do next, the camera hovering at her slumped shoulder. In such capable hands as the trio of Tsai, Liao, and Chen, such a deceptively simple scene can shatter you.

It’s easy to see why Tsai has worked with many of the same actors across decades; to be effective in one of his movies, you have to understand his particular cinematic shorthand. His films render real-life cinematic solely through how that life is observed, as opposed to reliance on bold-faced acting and clever camera tricks to capture the viewer’s heart and mind with a different notion of what life could be. A focus on the passage of time, whether much action occurs during that passage or not, is a landmark of many Tsai films and others that fall into the much-discussed category of slow cinema; in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, we contemplate both the time one spends inside a movie theater, communing with the audience and the images on the screen, as well as how the passage of time that has slowly rendered this particular theater obsolete, and turned the actors of Dragon Inn, once stars, into just another couple of anonymous audience members, dissolving in the rain.

Conclusion

As one is reminded throughout Goodbye, Dragon Inn, even when one goes to the movies alone, one does so to find a connection with others, whether it be the strangers in the auditorium with whom we may have nothing in common but a tendency to gasp and laugh at the same time or even just the characters on the screen. As the theater manager and the projectionist slowly but surely shutter their theater at the end of the dark, rainy night, one feels a tightening in one’s chest — is that it? Where will these lonely people go now? What will we all do if the cinemas close for good? Needless to say, sitting on my couch with my cat and a superhero film queued up on HBO Max, while easy enough, doesn’t have the same emotional resonance. Going to the movies reminds us that no matter what, we aren’t alone in this world — a beautiful, bittersweet feeling that, in an era of quarantine, is all the more necessary.

What do you think? What was the last film you saw in theaters? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn is screening in virtual cinemas beginning December 18, 2020.

Watch Goodbye, Dragon Inn

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!