Kīlauea’s Lava Lake Is Back, and Volcanologists Are Bubbling With Excitement

Like in many parts of the world, 2020 has been an atrocious year for America: pandemic, wildfires, hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, and more. “But then Kīlauea erupts, and we’re all like: ‘Yes!’” says Jackie Caplan-Auerbach, a seismologist and volcanologist at the Western Washington University.

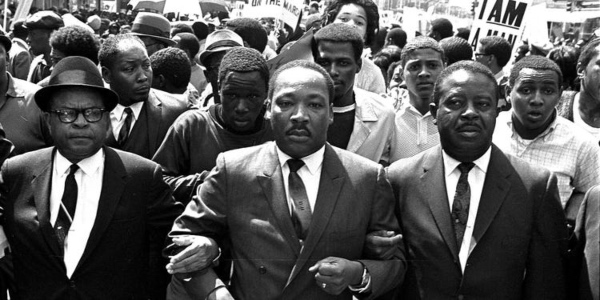

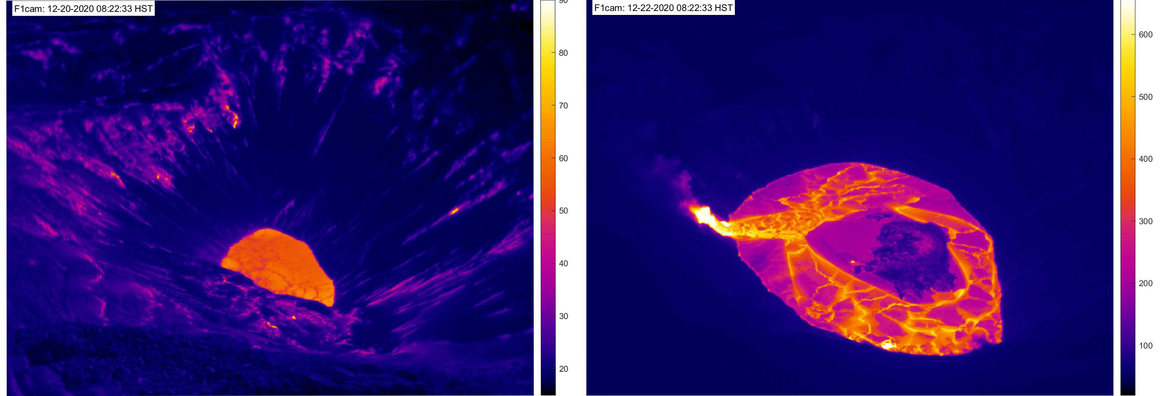

On December 20, 2020, at 9:36 p.m. local time, Kīlauea—the crowning volcanic jewel of the Hawaiian archipelago—woke up from a surprisingly brief slumber and began gushing again. Waterfalls of lava began pouring into Halemaʻumaʻu, the pit crater within the mountain’s cauldron-shaped summit. As of the morning of December 23, lava from two fissures continued to feed a growing lava lake—already more than 500 feet deep.

The volcano, making up the southeastern section of the Hawaiʻi’s Big Island, had been disquietingly silent as of late. The volcano had been erupting more or less continuously since 1983, eventually sustaining a lava lake within the summit caldera. But then at the start of May in 2018, it began a game-changing eruption sequence. In just three months, 14 square miles of the island were smothered in lava, 900 acres of new land had glommed haphazardly onto the shoreline, and the summit—exsanguinated of magma that flowed out of profuse eruptions on the eastern flank—collapsed to a crater depth almost the same height as One World Trade Center. Around 700 homes were destroyed by the flank eruptions, and the loss of property and business cost the state hundreds of millions.

Long before that eruption came to a screeching stop in early August 2018, the long-lived lava lake was gone. Water replaced it, eventually forming a muddy lake. By December 2020, no fresh lava had been seen for around 18 months.

“I love Kīlauea. Ever since I even knew about volcanoes, Kīlauea has been erupting,” says Jani Radebaugh, a planetary scientist and lava lake aficionada at Brigham Young University. “For [the lava lake] to have roared back, and it’s now twice as deep as that lake of water—I mean, it’s huge!” she says. “It’s fantastic. It’s so exciting.”

Unlike the 2018 eruption, this new extravagance is presently contained to the summit, far from any large concentrations of people. “Even though there’s uncertainty, and I know this eruption will progress, it’s wonderful to have to not worry about people’s homes and people’s lives immediately, or every day, while the eruption is going on,” says Christina Neal, who was the scientist-in-charge at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) from 2015 to 2020, and is now at the Survey’s Alaska Volcano Observatory.

The hope is that the lava lake within Halemaʻumaʻu sticks around, as it had for years, when it represented a rare portal into the planet’s underworld that scientists could study to decode the mysteries not just of Kīlauea, but of volcanoes all over the planet. To understand how the planet works, scientists need to get a look into the hephaestean kitchen that cooks up the magma that erupts into lava on the surface. Lava lakes are rare peeks at how that particular sausage gets made. “A Kīlauea eruption is something we can all be happy about,” says Ken Rubin, a volcanologist at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

But eruptions are idiosyncratic. What’s happening now could be an ephemeral profusion or, perhaps, the start of a new multi-decade eruption. “Like they say here in Hawaiʻi: You can’t predict Madame Pele,” says Rubin.

By any standards, Kīlauea has been a hyperactive volcano. Ever since it forged Puʻu ʻŌʻō, an effervescing volcanic coliseum on its eastern flanks, back in 1983, lava has been coming out in some form or another. By 2008, the volcano was firing on all cylinders, sustaining a new summit lava lake at Halemaʻumaʻu and a somewhat more erratic one at the twitchy, spewing Puʻu ʻŌʻō.

Long-lived lava lakes, contrary to how they are depicted in movies, are atypical for most volcanoes. It’s not understood why, but maintaining a direct pathway from a deep magma reservoir to a surface-level chasm is extremely difficult. You can count the number of persistent hadean pools today on one hand, and those that do exist are not easy to approach. The one bubbling away in Democratic Republic of Congo’s Nyiragongo volcano, sits within an on-and-off conflict zone. Others, like the one decorating Mount Michael, a steep 3,250-foot volcano on frozen-over Saunders Island, an islet a thousand miles from the nearest sizable landmass—Antarctica—are almost inaccessible.

The evacuation of Halemaʻumaʻu’s lava lake in 2018 was a loss for volcanologists. It was vast, easy to reach, and could be studied with intense scrutiny. But there were reasons to suspect it would return. History was one: It had hung on from at least 1823 until the 1890s. It popped up again in the new century and stayed put until 1924, but following several blasts it then went into hibernation again until 2008, before the plug was pulled yet again in 2018. Another comeback wouldn’t be unexpected. The other reason for optimism was rumblings in the ground: Scientists could hear its still-mostly-full 2018 magma cache refilling immediately after the 2018 eruption ended, indicating a future salvo at the surface was likely.

Like several volcanologists, Caplan-Auerbach suspected that there would be a longer pause between the 2018 paroxysm and this go-around. The showstopping performance of 2018 suggested a major change in the volcano’s underground plumbing, and that the recharge process could take a fair while. “I’m thrilled to be wrong,” she says. “I think it speaks to how voracious a volcano Kīlauea is.”

A new set of seismic grumblings developed in November, and the volcano’s surface began to warp slightly, indicating that magma had been injected into the shallow subsurface in a previously undisturbed part of the summit. “People knew that it was kind of ramping up, and something new, something different, was happening,” says Wendy Stovall, the deputy scientist-in-charge at the Survey’s Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, who joined the response to Kīlauea’s 2018 eruption.

According to Rubin, there was nothing to definitively suggest at that time that an eruption was imminent. “There were subtle signs that said, ‘Don’t worry, the volcano isn’t dead.’ That’s how I read that,” he says.

The onset of the eruption on December 20 was rapid, even with the warning signs. “It did kind of take people by surprise,” says Stovall. Spectacular though it may be, these somewhat sudden shenanigans aren’t entirely unexpected. “Kīlauea is doing what it’s supposed to do,” she says. “It’s building itself.”

The new summit eruption, which quickly and harmlessly vaporized the pit’s erstwhile water lake, could evolve in many ways. It could once again trigger a flank eruption, or stay confined to the summit. It could be short-lived or prolonged, it could even grow to fill the entire summit. “It’s not been that long in the past that all of Kīlauea was filled up with lava,” says Radebaugh. But it’s different than the last time the lava lake filled. In 2008, that magma came rushing up from below—this time it’s oozing out in lavafalls from the sides of the crater. “Everything’s on the table,” says Caplan-Auerbach.

But merely seeing Kīlauea burst into life again has volcanologists thrilled. “Every time the volcano does something new, it’s a chance to refine our understanding,” says Neal.

“To me, the current eruption is somewhat of a relief,” says Tim Orr, a geologist at the Survey’s Alaska Volcano Observatory who previously worked at HVO. “Kīlauea is going to erupt, regardless of the length of the quiet periods. When nothing is happening, there is always a bit of worry linked to the uncertainty of what and where things might start up.”

For others, the impact of a volcano coming back to life is a little more visceral. “No one who has ever seen lava will ever forget any part of that experience. The smell of it, the sound of it, the look of it, the feel of the heat if you’re close enough,” says Caplan-Auerbach. “It is the most wonderful thing to see lava again.”