These Coded Wine Glasses Were Used for Treasonous Toasts

This glass has a secret. It’s encoded in the images inscribed around the bowl: a blazing star, an oak leaf, a rose blossom, and two delicate buds sprouting from a thorny stem. They may seem like mere decoration, but to the right eyes, they were a message, and a dangerous one at that. The original owners of this glass must have been careful who they let see it. In England, circa 1745, toasting with it could constitute treason.

Taken together, the rose, oak leaf, and star tell a story of loyalty to a banished king, James II of England. The blooming rose stands for James’s son and heir (known to his enemies as the “Old Pretender”); the oak leaf is a symbol of the House of Stuart, James’s family line; and the star reflects the hope that the Stuart family will once more rise to glory.

Crowned in 1685, the Catholic King James II reigned over a largely Protestant country. His faith was tolerated so long as his Protestant daughter, Mary, remained his presumptive heir. But in 1688, James had a son, stoking fears among the Protestant populace who believed a Catholic dynasty would lead to “popery” and absolutist rule. James’s son-in-law, the Dutch prince William of Orange, seized the opportunity and brought the Dutch fleet to English shores. James fled, and Parliament handed the crown to William, making him King William III of England.

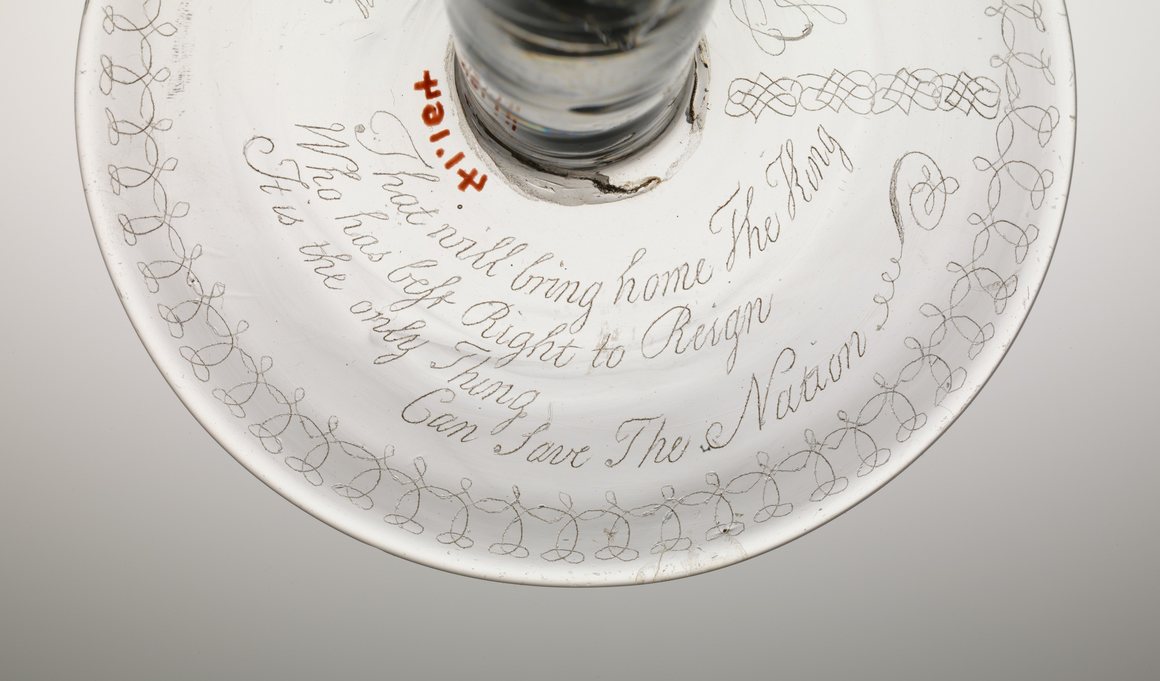

But King James II’s loyal adherents, known as Jacobites, continued to hope for the return of their exiled king. This loyalty long outlasted James II himself. When he died in 1701, the Jacobites transferred their loyalty to his son, James Francis Edward Stuart. Many were Catholic; others were simply attached to the principle of heredity in royal succession. Forced to conceal their treasonous affiliations, they indulged in secret shows of support, which included collecting glasses etched with Jacobite symbols, to be locked away in special cabinets and brought out only in select, safe company.

Just like the glasses themselves, Jacobites’ manner of toasting contained a secret code. When they raised a glass to the king, they took care to hold it over a finger-bowl on the table, signifying that their toast was addressed to the king “over water”—that is, the exiled “King James III” overseas. And after King William III died in a riding accident, Jacobites drank to “the little gentleman in black velvet”—meaning the mole that tripped William’s horse.

Jacobitism spread and flourished in the convivial atmosphere of taverns and coffee-houses. In 1715, the plots laid in these secret meetings broke out into open rebellion. The Earl of Mar raised an army of some 16,000 men, mostly from James II’s native Scotland. The forces found themselves outnumbered and the uprising floundered. It was followed by a more successful attempt in 1745, led by “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” King James II’s grandson. But after the 1745 rebellion was defeated, Jacobitism was driven once more into the secrecy of private clubs and coded toasts.

One particularly playful example is a tray covered in what looks at first glance like abstract smears of paint. When a curved mirror is placed on the tray, the smears resolve themselves into a portrait of James’ infamous grandson Charles, nicknamed “Bonnie Prince Charlie.”

Equally odd are the striking species of Jacobite cups known as “coin glasses.” A tour-de-force of glassblowing, their stems swell out to form transparent bubbles that house coins from the reign of James II or one of his predecessors. On the face of it, there’s nothing treasonous about honoring a legitimate king. But to Jacobites, these old coins hearkened back to the golden time before William III disrupted the line of succession. More than that, the coin served to symbolically return the exiled king to his loyal supporters: Every time they drained the cup, they saw his face. As Neil Guthrie writes in Material Culture of the Jacobites, “When you drink the king’s health he is there before you.”

Just like a treasonous toast to the “king over water,” these artifacts tease, playing with concealment and disclosure. At a moment’s notice, they are ready to reveal themselves to a fellow sympathizer, or retreat behind a veneer of plausible deniability. It all depends on if you know how to crack the code. Consider the wineglass adorned with the rose, the oak leaf, and the star. Innocuous symbols, at first glance, but once we know how to decode them, the story begins to unfurl. The owners may be long dead, but the objects they left behind continue to tell their secrets.