TRAINED: A Dynamic Concept Frozen Over

Like many short films, Trained finds a unique phobia/concept (Siderodromophilia: someone who cannot get aroused unless they’re on or around moving trains) then applies it to two emotionally involved people in an attempt to raise immovable questions.

Comedy or drama?

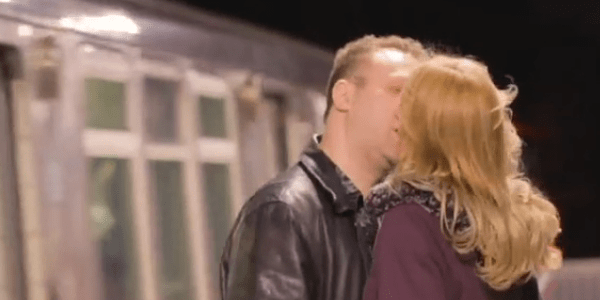

As aforementioned, the idea of finding a relatively unique phobia or personal tendency and applying it to a short piece is a well-worn technique. It wouldn’t be if it didn’t work. In the case of Trained, the same rules apply but with very different emotional perspectives depending on how much you know about the story before the film begins. With knowledge of Emma’s (Jenny Diamico) bizarre sexual practices before the film begins, comes an emotional attachment to the sounds and images of trains throughout the film. However, by the time you reach the mid-point, one starts to think about what questions are actually being explored and how the narrative is furthering the specifics of such a topic.

Are we supposed to be consuming this narrative with empathetic feelings or supposed to be laughing at the ridiculousness of it all? It’s difficult to know, which writer/director and actor Yuri Rutman is trying to portray here. The other perspective is that of someone who has no idea what the film is about. Which admittedly (in any case) makes a story more interesting, with this point of view you may not understand Emma’s erotic tendencies until later into the film’s runtime, which sits just underneath 18 minutes. It’s likely a better viewing experience but it doesn’t solve any of the short film’s issues.

The empty station

Those issues are largely emotional. While there are heavily prominent audio-mixing problems that draw you out of scenes, especially when you’re ready to hear dialogue from characters who spend most of the film in silence, any interesting moments happen between the far too-often sexual glimpses and discouraging human interactions. The writing subconsciously makes us side with Emma’s mental illness, knowing full well she probably can’t get better by the time the film is over. The script plays its cards early and poorly, by focusing on how this is going to affect their sex-life. But outside of their sex-life, there doesn’t seem to be much ‘life’ between these two people at all. If such is the case, why on earth would Emma’s character play second fiddle to a middle-aged, apparently normal, white-male, Jake? Surely, it’s Emma who should be the lead, doesn’t she have the most to lose?

We’re never shown their lives outside of the moments the script traps us in; which are inherently intimate moments, such as a back massage, foreplay or merely waiting for a train (the best moments of the film). This is as frustrating for us as it is for the lead character; Jake, who’s desperate for a ‘normal’ sex-life. Nevertheless, it’s fairly ridiculous because it’s hard to see any reason why or how these two are together or would stay together considering the unique situation. I suppose none of this becomes more obvious than through the psychiatrist (Jason Elkins) who hardly has any lines but also seems to have no emotional needs, wants, opinions, or connection to the narrative of the film. Simply acting as a placeholder or plot device. Thus, every time we’re with Jake recounting his relationship, it feels kind of shoddy and bland. Who is Jake? According to the 18 minutes; just someone who wants a good fuck with this particular woman because the plot makes it so.

Rails

Despite all this, Jenny Diamico does makes some strides as Emma. For some reason, her toil with being sexually aroused by trains naturally comes off as embarrassing but totally truthful. As depicted in probably the best and most interesting scene, when she becomes frustrated when not a single train turns up in ninety minutes and decides to regale to Jake, the next few trains on the minute-to-minute schedule. Admittedly, she’s cornered into a difficult position, thus we connect to her easily. In turn, making Jake more unnerving and uncomfortable (especially when he wants to be intimate in non-train related situations) than he means to come off. The free-spiritedness of some of the film’s editing and cinematography are positives, being the few moments when the energy of the trains actually springs to life on screen, but they don’t last long.

Trained focuses on a unique idea but never seems to spring up or explore what’s beneath the surface of it’s chosen gimmick. When it does try, it feels empty, ill, and flat, even slightly uncomfortable. For anyone who does suffer from this illness; Trained will only make them feel even more alienated. Making it’s viewing an odd, offbeat experience that offers nothing new, neither to short film nor siderodromophilia sufferers.

Have you seen trained? What did you think? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!