Meet the Rats That Wear Protective Poison Armor

In a converted cattle shed in central Kenya, a mischief of rats is getting up to some. Bristling with energy, the salt-and-pepper animals—African crested rats, which look like skunks that tumbled around in a dryer—gnaw on the stalks and leaves of a poisonous plant. Raising the fur on their flanks, the rats use their tongues to lather their bodies with a mixture of spit and toxin.

Recently, a team of researchers including scientists from the University of Utah and the Mpala Research Centre in Kenya took a look at the secretive nature of the elusive rats, the only mammals known to sequester toxins from plants. (The area’s indigenous hunters have used the plant in question, Acokanthera schimperi, to make poison arrows.) The team’s results, published in the Journal of Mammalogy, revealed that the rats get by with a little help from their friends and significant amounts of fatal poisons coating their flanks.

The study—the most substantial look into the rats’ lifestyle in nearly a decade—involved capturing live rodents and shuttling them to the shed, where their behaviors were filmed. A couple times, two rodents were caught in the same trap, leading the researchers to recognize the rats as social creatures. “They must have really been attached to the hip,” says Katrina Nyawira, a researcher at Oxford Brookes University and a coauthor of the recent paper. “That kind of switched our idea to do with their behavior—they’re not really solitary animals, and they’re very attached to their family members.” In captivity, rats were grouped based on whether the research team had reason to believe they were amicable in the wild. (“We didn’t want sort of a rat Fight Club breaking out,” says Sara Weinstein, a biologist at the University of Utah and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, and the study’s lead author.) The animals anointed themselves with poison under cover of night and the watchful eye of the team’s cameras.

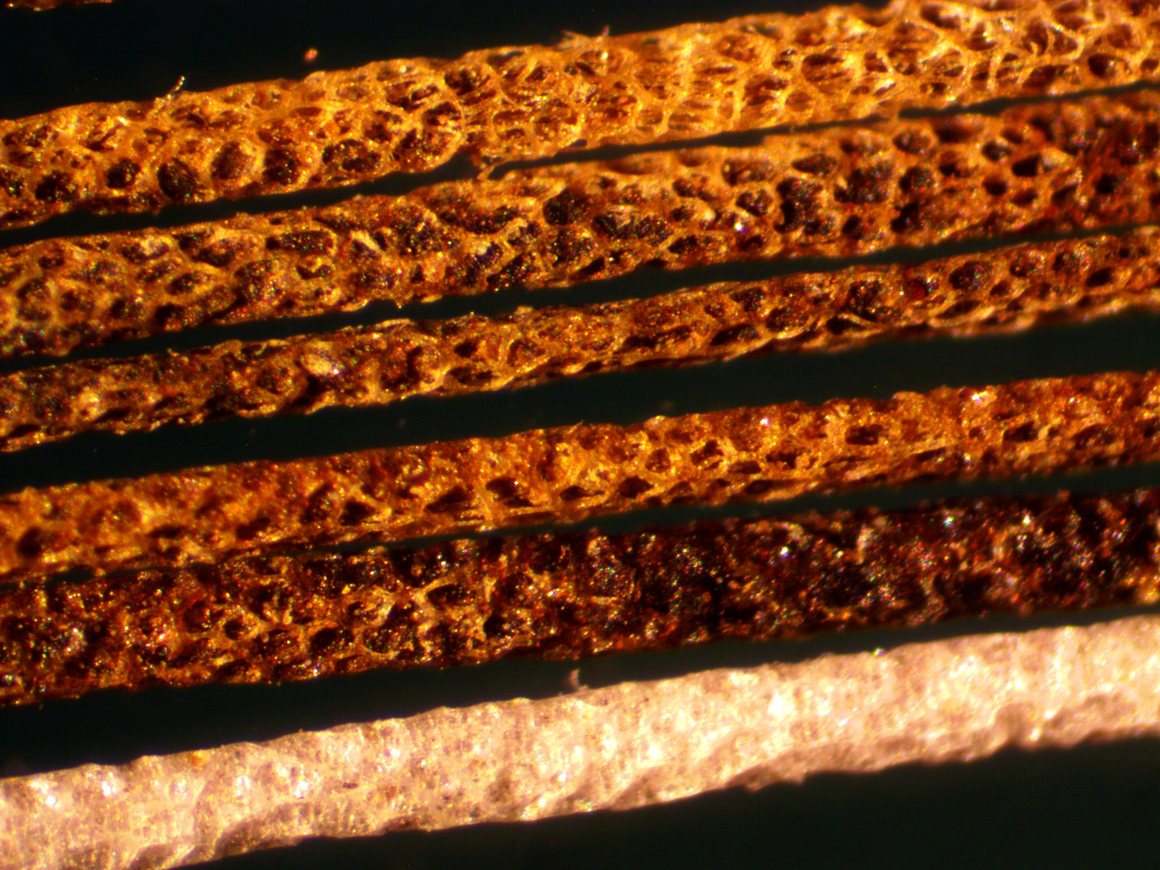

Researchers don’t yet know why the rat is immune to the poison’s dangers, but the substance certainly helps the creature get by. The animal’s sides are covered with specialized hairs, which have crypts that soak up and store the poison and pull out of the creature’s body more easily than the ordinary hairs covering the rest. If a predator goes to take a taste of the flank, it’s more likely to end up with a mouthful of poison-soaked fur. “It’s like an arms race,” Weinstein says. “The rat really doesn’t want to be sampled by a predator.” And a poison-laced rat is not the wisest choice for dogs, coyotes, or other predators seeking a snack.

Covering itself with a deadly salve is just one of the rat’s suite of defensive tricks. “When we map it out taxonomically among other rats, it stands on its own,” says Bernard Agwanda, a mammalogist with National Museums Kenya, and an expert on the rodent species in East Africa. “The skull of the rat is canopied; there are double layers of tough bones protecting the brain.” It also has large salivary glands—”some of the largest compared to its size,” says Agwanda—which likely help the rats keep an ample spittle store for mixing with the tree toxin.

“That tree is so potent that no one ever wants to deal with it,” Nyawira says. No wonder the rodent took this long to offer up the secrets of its social life: Even humans wanted to stay away.