Witch Kitsch and Dark History in Germany’s Harz Mountains

This story is excerpted and adapted from Kristen J. Sollée’s Witch Hunt: A Traveler’s Guide to the Power and Persecution of the Witch, published in October 2020 by Red Wheel Weiser.

To German witches—hexen—the Harz highlands of northern Germany is home, a mountain range steeped in pagan lore. Here, Quedlinburg, a dazzling medieval town untouched by World War II, is a place of whimsical winding streets and more than a thousand fully preserved half-timbered homes. The town has a rather feminist bent to its history, as women wielded great political influence here for over 800 years. In 936, the widow of the Saxon king Heinrich I, named Matilde, founded a convent, and the abbess of that convent would continue to hold considerable power in the town and surrounding regions until Napoleon invaded in 1802.

Most descriptions of Quedlinburg in travel literature include the phrase “fairy tale,” and true to the Grimms’ classic German fairy tales—not their softened American versions—this UNESCO World Heritage Site has a dark side.

During a walk through, I didn’t see a single piece of trash, but I did notice apotropaic symbols, such as hexagrams and crosses, carved into the beams of the aged buildings to ward off sickness and keep demons and witches at bay. Like many German towns, Quedlinburg had its own early modern witch hunts. But they didn’t have nearly the impact as the propaganda that later sprang from them would, for Quedlinburg is also the birthplace of one of the most misinformed assertions about the early modern witch hunts.

Between scholars, feminists, and practicing witches, there have been divergent views on how many people were accused of and executed for witchcraft in early modern times. American historian Anne Barstow estimates 200,000 people accused and 100,000 put to death, but she admits to the difficulty of coming up with such numbers. In Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, Barstow writes: “Working with the statistics of witchcraft is like working with quicksand.”

Australian historian Lyndal Roper estimates half of Barstow’s number in Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany. “Over the course of the witch hunt, upwards of perhaps 50,000 people died,” she writes. “We will never know the exact figure because in many places the records of their interrogations have simply been destroyed, with allusions made only to ‘hundreds’ of witches killed.”

German historian Wolfgang Behringer concurs with Roper in Witches and Witch-Hunts: “For witchcraft and sorcery between 1400 and 1800, all in all, we estimate something like 50,000 legal death penalties,” he writes, adding that there were likely twice as many people who were punished with “banishment, fines, or church penance.”

But others—including feminist writers beginning with Matilda Joslyn Gage in the late 19th century and continuing with Margaret Murray and Mary Daly in the 20th—have bandied about the absurdly large number of nine million. Wonder where that came from? Look no further than the quaint old town of Quedlinburg.

Ronald Hutton explains in Witches, Druids, and King Arthur that the 18th-century German historian Gottfried Christian Voigt supposed that more than nine million witches were killed in Europe based on the witch hunt death toll in his hometown. Voigt “had arrived at this simply by discovering records of the burning of thirty witches at Quedlinburg itself between 1569 and 1583 and assuming that these were normative for every equivalent period of time as long as the laws against witchcraft were in operation,” Hutton writes. From there, “he simply kept on multiplying the figure in relation to the presumed population of other Christian countries.”

Inside this oddities museum, an ahistorical bricolage of fact and fiction rubs elbows in every room. A panel about the 15th-century witchcraft treatise Malleus Maleficarum, a befragungsstuhl (spiked interrogation chair), herbs associated with witchcraft, and logs assembled in a witch-burning pyre were near displays featuring vampires, werewolves, and zombies. There were so many rooms chock-full of occult paraphernalia I could barely see everything. It was an apt harbinger of what was to come.

A sunny walk through a wooded area across from the Obscurum led me to the Funpark, where my doppelgänger—a smiling blonde witch statue in a fuchsia hat and dress—welcomed me. I passed a smattering of children’s rides before joining families in line for the gondola that would lift us up to the Hexentanzplatz, the Witches’ Dance Floor. Hundreds of feet in the air alone in my own glass car I had a panoramic view of the dense wilderness of the Harz Mountains. Sinister rock formations poked up like witches’ fingers summoning me from the forest below.

Nestled high above the Bode Gorge, the Hexentanzplatz is a rocky plateau with strong Saxon roots. The clearing was supposedly where the Saxons once held rituals and sacrifices to their mountain gods and goddesses, and it thus retains a heathen tenor, drawing countless revelers every year for Walpurgis Night.

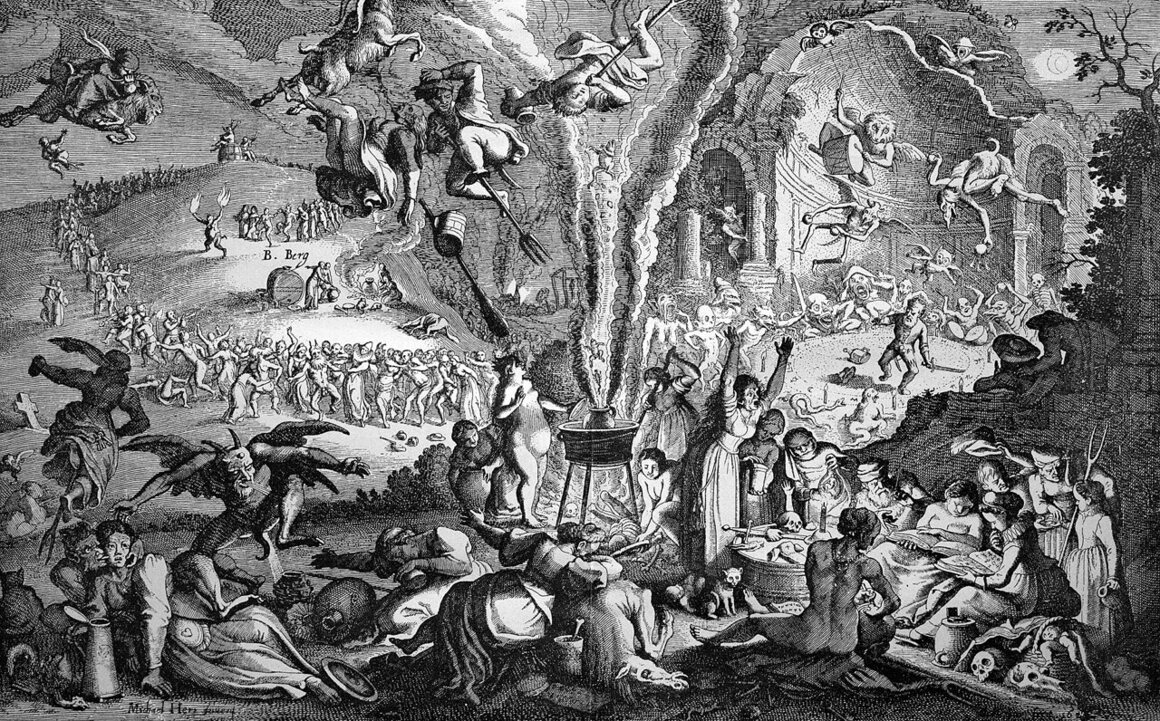

“We know that all over Germany a grand annual excursion of witches is placed on the first night in May (Walpurgis), i.e., on the date of a sacrificial feast and the old May-gathering of the people,” writes folklorist Jacob Grimm in his 1835 exploration of Germanic myths, Deutsche Mythologie. “The witches invariably resort to places where formerly justice was administered, or sacrifices were offered,” he continues. “Almost all the witch-mountains were once hills of sacrifice, boundary-hills, or salt-hills.”

The Upper Harz region was once described as “wilder, its rock scenery more grotesque” than the Lower Harz, in an 1880 travel guide published in London Society. Long before the area’s commercialization, long before a theme park was built, Thale had “the best, but also the dearest, inns in the Harz.” The 19th-century English travel writer goes on to describe the Hexentanzplatz as “a perpendicular cliff … which affords a yet finer view of the whole mountain chain.”

Once at the top, I was overwhelmed by German signs pointing in all directions to different attractions. The Hexentanzplatz is now part–nature preserve, part–witch theme park, with an open-air theater, a zoo, a multipart museum, and many witch-themed refreshment stands and gift shops. My first instinct was to follow the crowds, which led me to a central area with statues of a naked Devil and witch that children were treating like jungle gyms.

One young girl straddled a hunched witch figure whose protruding backside was home to a large spider. She steadied her baby sibling in front of her as the two giggled. Another young boy studied an animal demon at the witch’s side, while other children posed with the Devil manspreading (demonspreading?) on a large rock. The Dark Lord’s genitals are carved in great bronze detail, rubbed to a bright sheen, presumably by visitors pawing at them for good luck.

Nearby was the Hexenbufett (Witch Buffet), where folks were gorging on fast food, right near the edge of a rock overhang above a thousand-foot drop. Shutting out the noise, I focused on the alluring and foreboding mountain terrain. (I heard only German in Thale, and no one even tried to speak English to me when I fumbled awkwardly.) Moving away from the crush of screaming children and their parents, I entered the Walpurgisgrotte section of the Harzeum. It was eerily empty and offered an even stranger mix of material than the Obscurum. In every dim, musty corner, witch stereotypes came to life through creepy mannequins set against elaborate tableaux.

A solitary sorceress posed in a room full of potions and bundles of dried herbs. A witch mom and devil dad watched their hellspawn lie on the living room floor, playing with a pentagram board game covered in snails. A woman in lingerie beckoned from a house covered in hearts and beaming red light. A wrinkled hag with long gray hair grinned in front of a cottage while a black cat perched on her shoulder and a demon peeked out from the window behind her. All the most vilified forms of femininity associated with witches—childless women, monstrous mothers, old women, promiscuous women—were represented.

Amid more witch torture devices I saw contemporary witchcraft ephemera—tarot, runes, and spirit boards—surrounded by cobwebbed candelabras and skulls. I spied what appeared to be death masks on the wall, in addition to a small child wearing a turtle shell as a hat. Right before I left, I walked by a scene with a woman in a wedding dress fanning out her credit cards and holding the leash of a man on all fours, because every woman is a witch in the eyes of her husband, I guess?

Darkly humorous and extraordinarily weird the Walpurgisgrotte left me a bit wobbly as I transitioned back to a beautiful sunny day on a mountaintop. The epitome of the mythical German forest lay below, and around me, families with young children seemed not to give a second thought to the surplus of witches and devils lurking about—it was all in good fun.

The early modern witch—particularly in Germany—was entrancing but equally, if not more so, repulsing. If she had beauty, it only concealed rotting hag flesh beneath. I felt this unsettling juxtaposition viscerally in the Harz when confronted with bald commercialism offset by breathtaking natural beauty and the real horrors of witch-hunting history masked by the ghoulish glee of kitschy witch attractions.

I was constantly shocked, mouth agape, with no one to share my surprise. Horrified one moment, awestruck the next, and overtaken by demonic cackles at the absurdity of it all.