The Messy Business of Scrubbing 2,000 Years of Bird Poop From an Egyptian Temple

The sands of time ravage all, stripping structures from the Parthenon in Athens to monuments in Persepolis of their color. But in rare cases, the past prevails, and structures retain hints of their once-vivid polychromy. The sandstone vestibule (or pronaos) of the temple of Esna, abutting the Nile about a half hour south of Luxor, is one such example, keeping its color with remarkable success. According to an Egyptian-German team restoring the temple, that preservation is a product of soot and bird poop.

Built during the reign of Claudius, between the years 41 and 54, the temple at Esna is younger than many other Egyptian temples you may think of. It was once one of three in the city, but the other two were deconstructed during the Napoleonic era for their limestone. (The surviving temple should consider itself lucky that it is sandstone, which has fewer secondary uses.) The temple was likely in use for religious purposes until about the third century.

The temple has accumulated the detritus of nearly two millennia: Over the years, people came and squatted, making tea and burning fires; craftsmen temporarily set up shop below its high ceilings. By the 19th century, the temple had become a storage room. In the structure’s early days, the exterior was “proper and clean,” says Christian Leitz, an Egyptologist at the University of Tübingen and project lead on the ongoing restoration work at Esna. “There were a lot of rules on how to keep your temple clean, but after it was abandoned, it was just a building,” Leitz says. “Nothing more.”

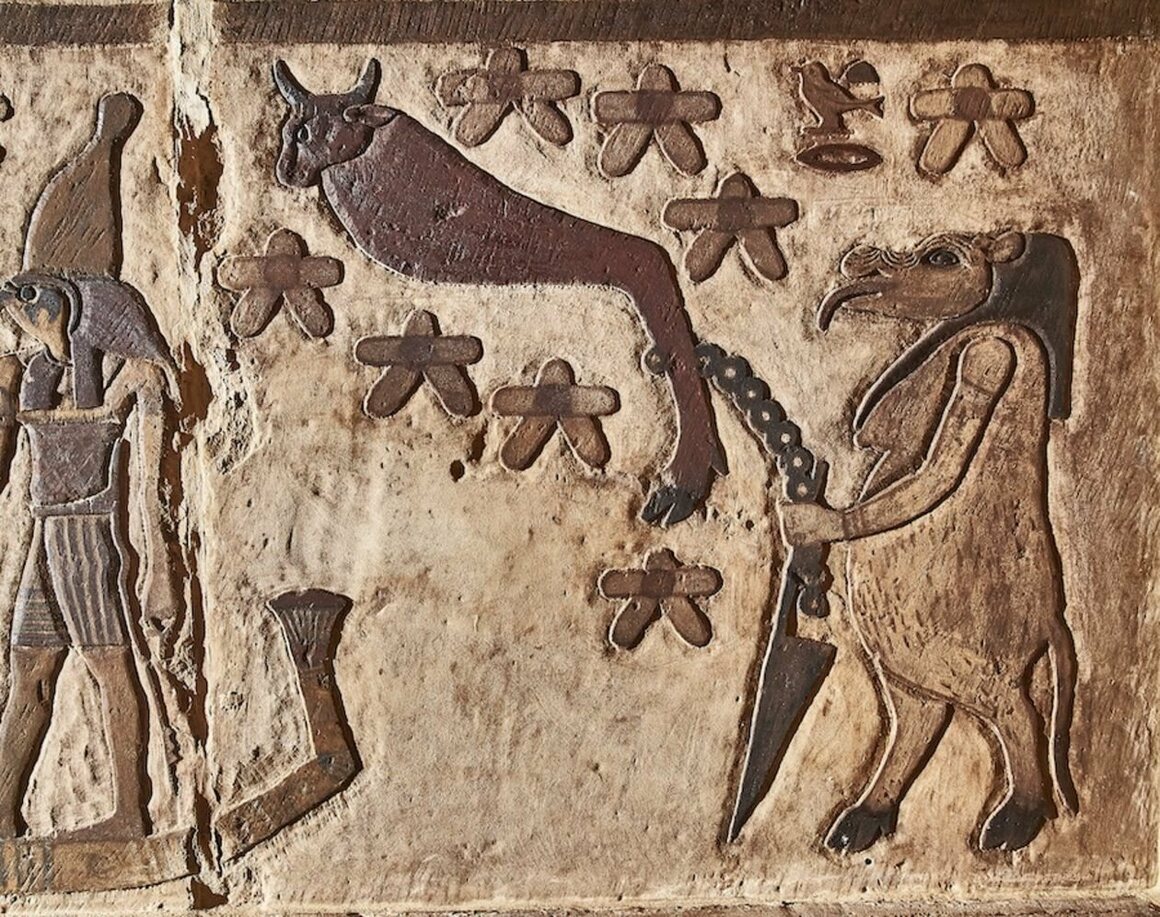

Birds roosted atop its columns and defecated on its walls, and a buildup of their excrement and soot accreted on the temple’s vivid descriptions of ancient Egyptian constellations and history, shrouding them. Those unintentional accoutrements didn’t harm the artwork beneath, but Leitz’s team has now cleaned the mess off, revealing the original colors of the temple’s paint job, which include cartouches naming the Emperors Hadrian and Trajan. The research team, which also included Hisham El-Leithy of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquites, found the never-before-reported names of several Ancient Egyptian constellations alongside known ones including the Big Dipper (then known as Mesekhtiu) and Orion, or Sah.

The poop and soot are carefully removed with a solution of alcohol and distilled water applied to the temple walls with Q-tips and paper, which remove defacements without damaging the intentional paint underneath. When the paintings come to the surface, the deep forest greens of ferns, the mustard yellow bands on columns, and the cerulean skin of the local god Khnum are extremely vivid.

Details of the ceiling suggest that the temple was unfinished, Leitz says. “If you are decorating a temple, you have three working steps,” he says. “You start with the preliminary design, which is inked, and somebody with a chisel makes the relief. The last step is the painting. Sometimes they stopped after step one, for whatever reason.” The ceiling of the Esna temple still includes some ink.

The careful cleaning takes time, even when the research team isn’t slowed by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Before progress slowed, 15 conservators spent four months restoring just one of the temple’s seven ceilings, Leitz says—and there are 24 columns to freshen up, too. The work will continue, and the team also plans to set up nettings to protect the walls and spikes to keep the pigeons at bay, in the hope that future conservators will have less of a mess to contend with. “If there are small parts of the wall that are broken down, we are closing them [so] that the birds have no chance to get in,” Leitz says. “Not even a sparrow.”