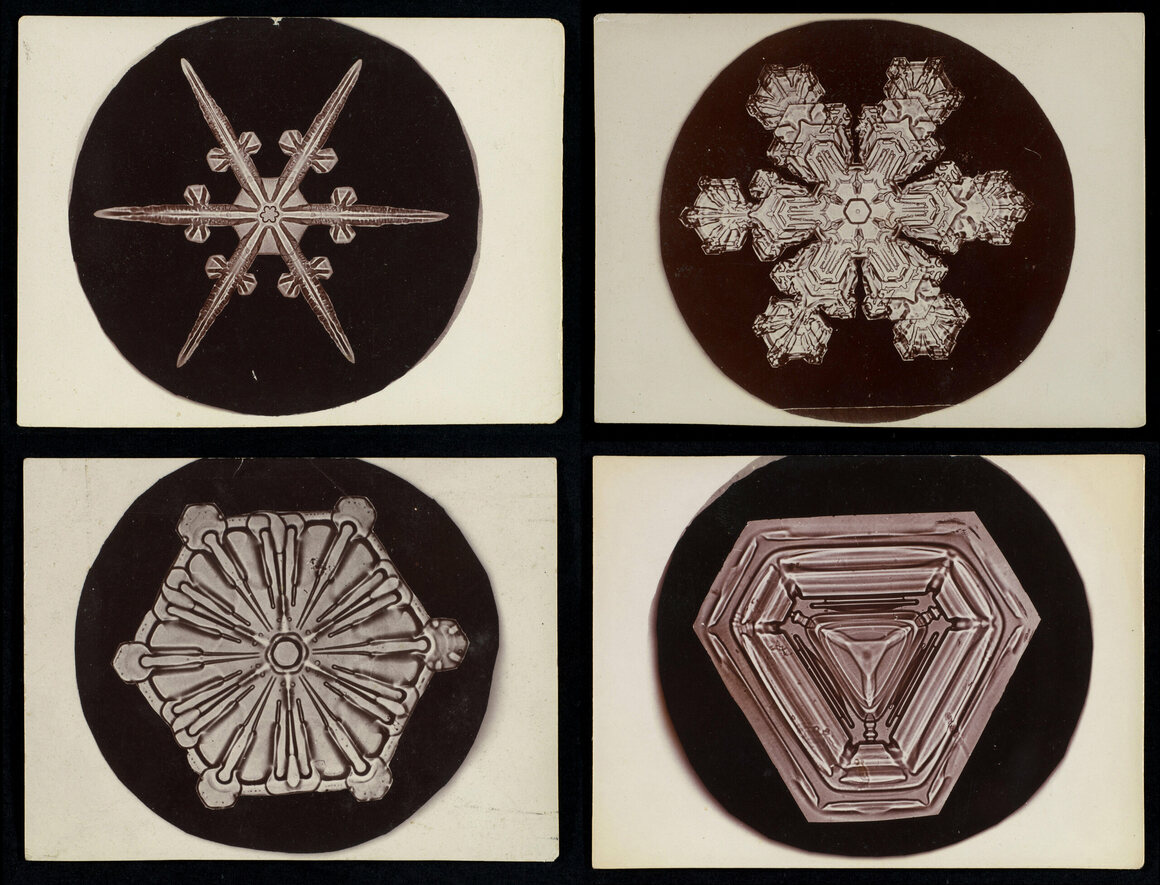

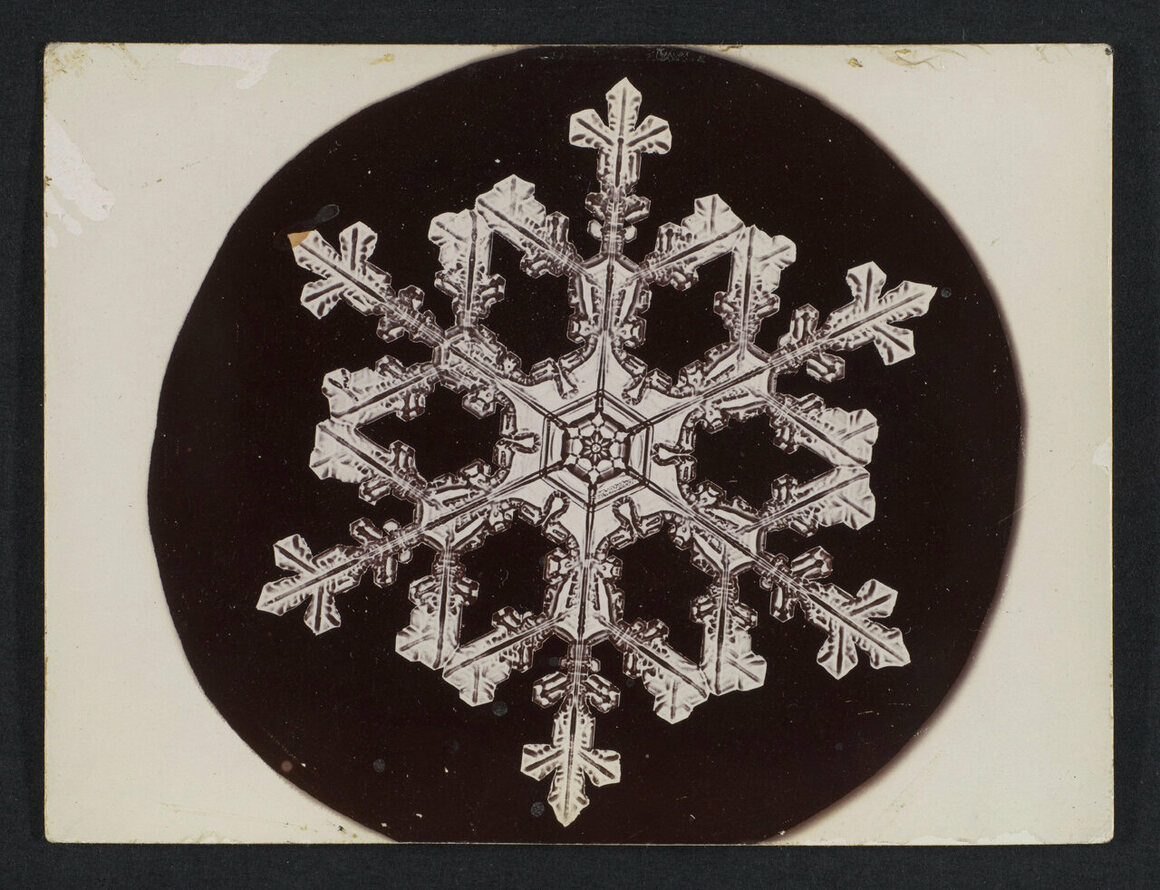

The Microphotographic Wonders of Vermont’s ‘Snowflake Man’

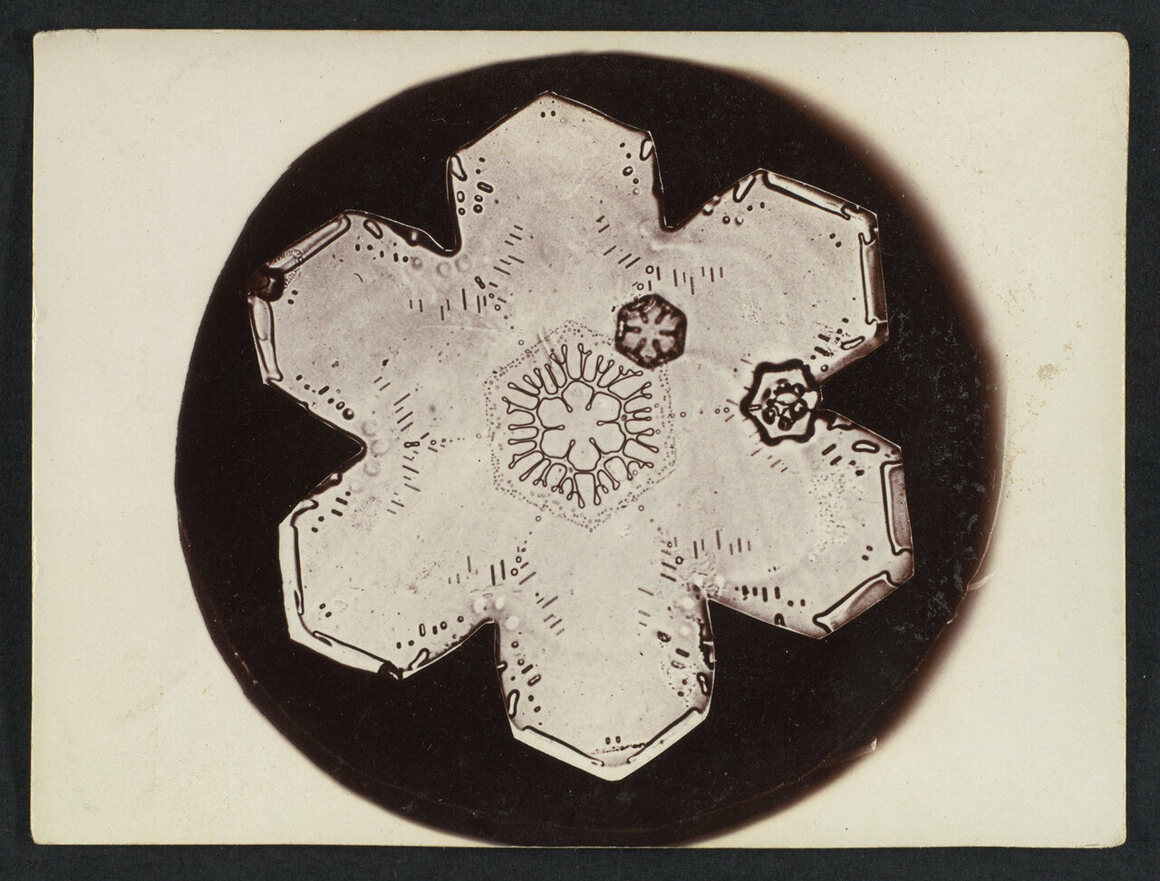

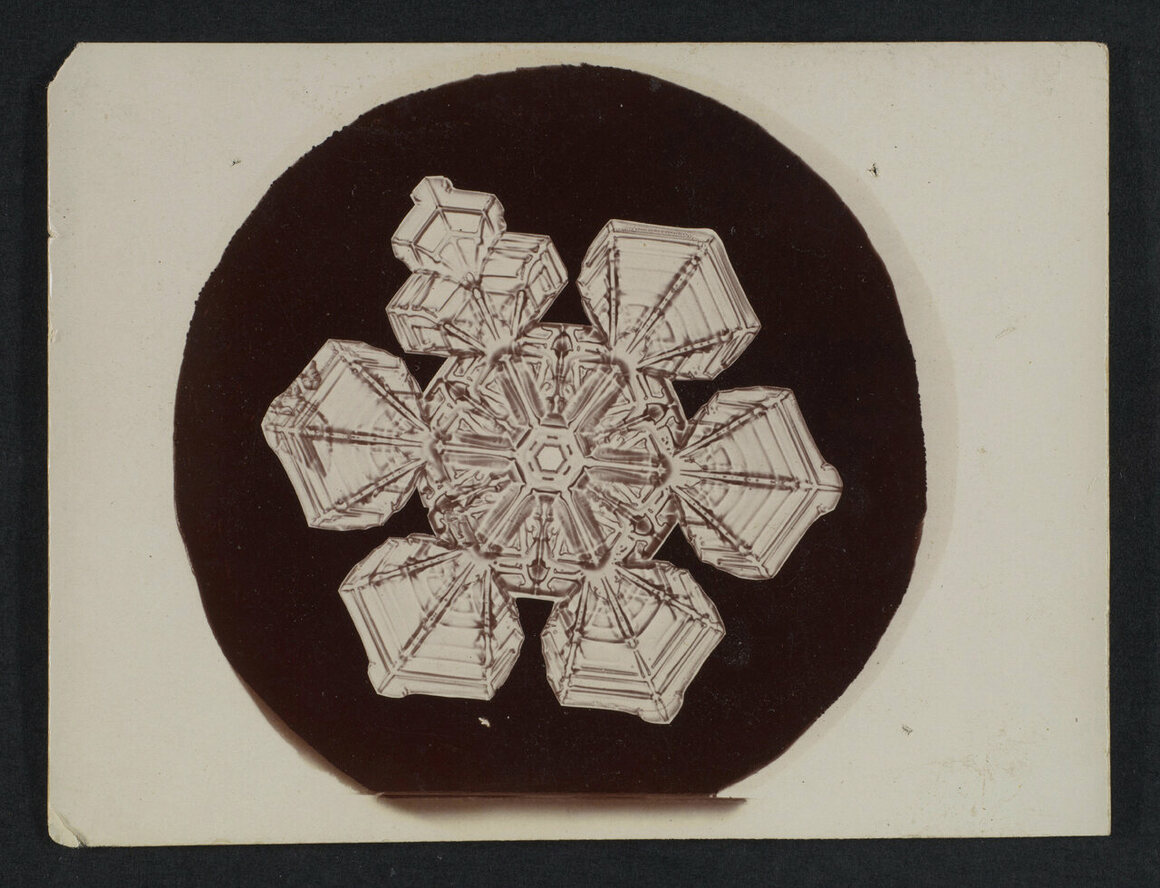

Wilson Bentley called snowflakes “nature’s wonder gems,” possessing “an infinity of beauty,” and wrote that when they fell, “the mysteries of the upper air are about to reveal themselves.” The self-educated meteorologist was the first person to make a successful picture—“photomicrograph”—of a snowflake in 1885, and the first to claim that no two are alike.

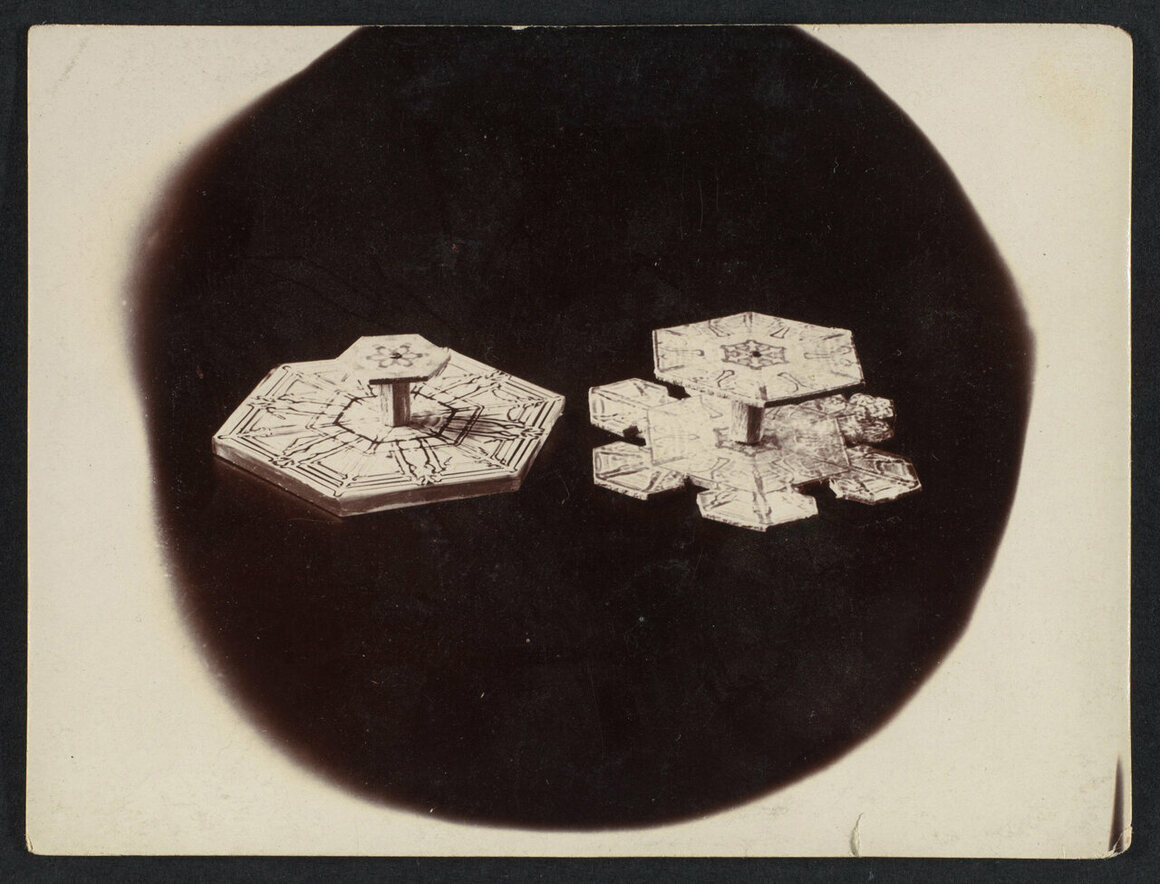

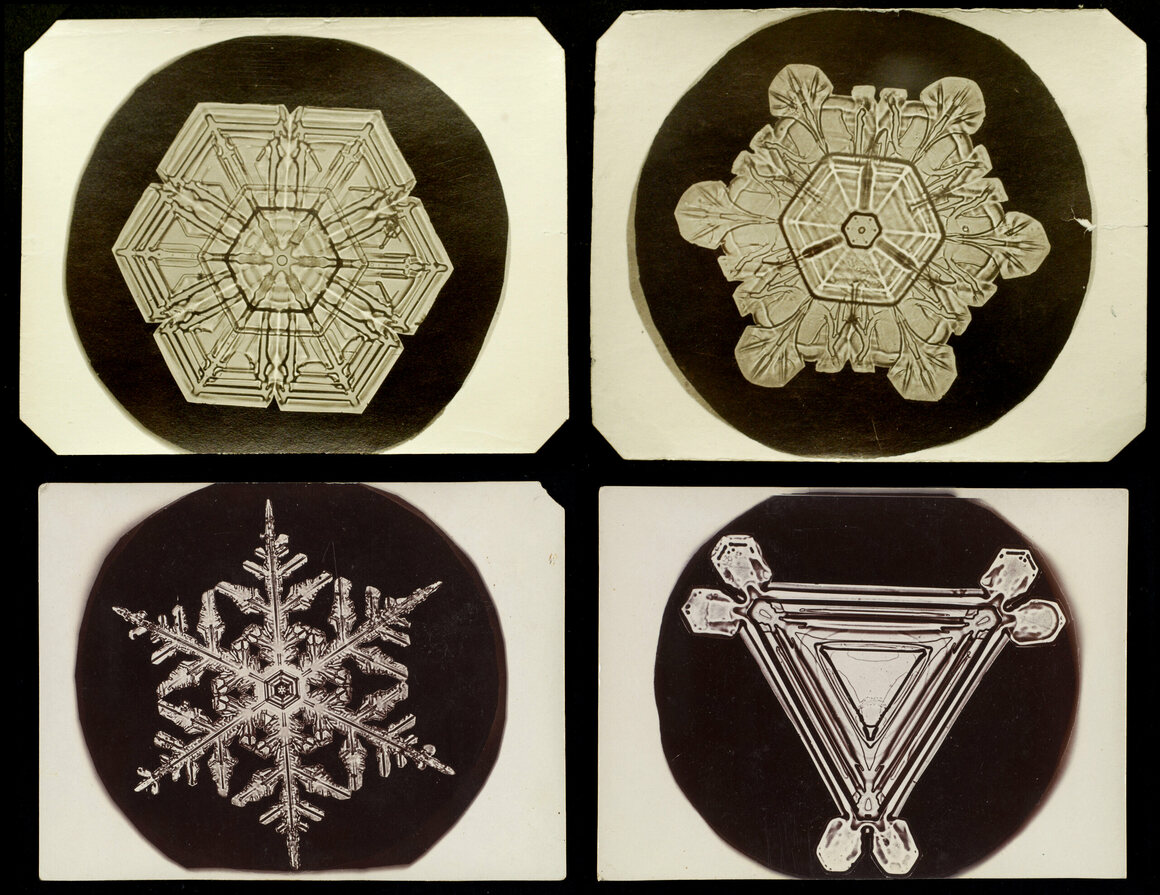

He provided strong evidence for this assertion by photographing more than 5,000 “snow crystals” (as he called them), and saw that each was fascinatingly distinct: some flawless in ornate and icy symmetry, others more charming for their subtle, delicate imperfections.

Bentley’s love of snowflakes started when he was given a microscope for his 15th birthday. Working on his family farm in Jericho, Vermont, where he lived his entire life (and where 95 inches of snow falls each year), he was a keen observer of the natural world. He initially sketched the snowflakes he saw through his microscope, but eventually he figured out a way to combine a camera with a compound microscope to magnify and capture every detail of the fragile structures. It was cold and difficult work. Wearing mittens during long hours in freezing New England winter, with only minutes before his subjects would melt, Bentley devised a painstaking method: He caught and transported the tiny wonders on a blackboard, placed them on microscope slides using a piece of straw plucked from a broom and a chicken feather, illuminated them with daylight to expose light-sensitive glass plates, and increased the images’ contrast by scratching out emulsion.

By photographing through every Vermont winter for the rest of his life, Bentley honed his observational skills: “The best time to study snowflakes is during a cold snowfall, when the temperature ranges from 20 degrees F above to zero or below, when the barometer is rising, and after the wind has shifted from easterly or southerly points to westerly or northerly ones,” he wrote. Bentley also explained technically why these winter phenomena are each so distinct, because they form as they fall from various heights in the atmosphere, constantly modified by changing conditions such as temperature and humidity. Though he was nicknamed the “Snowflake Man,” ice crystals were not his only obsession. Bentley was also bewitched by raindrops, dew, and clouds, and had published his thorough investigations on atmospheric marvels in such magazines as National Geographic and Popular Mechanics. Before Bentley died in 1931—from catching pneumonia in a blizzard—he published a book, Snow Crystals, with physicist and atmospheric researcher William J. Humphreys. Naturally, the book was illustrated with more than 2,400 of Bentley’s photographs—no two jewel-like images the same.

Decades later, and following countless advances in microphotography, his laborious images still enchant.