Why Longtime Alaska Residents Are Called ‘Sourdoughs’

When Trisha Costello bought the Talkeetna Roadhouse 25 years ago, she was given three things: the deed, a set of keys, and a sourdough starter that the previous owner said dated back to 1902.

The year-round population of Talkeetna, Alaska, hovers around 900 people, but in a normal year, Costello’s crew churns out hundreds of pounds of dense sourdough hotcakes per day, each dappled with a cosmos of mixed berries or chocolate chips and hanging over the side of the plate. They’re enormous, and enormously popular, with tourists, with locals, and especially with climbers, who often stop by for a meal before starting their summit attempts of Denali, the highest mountain peak in North America.

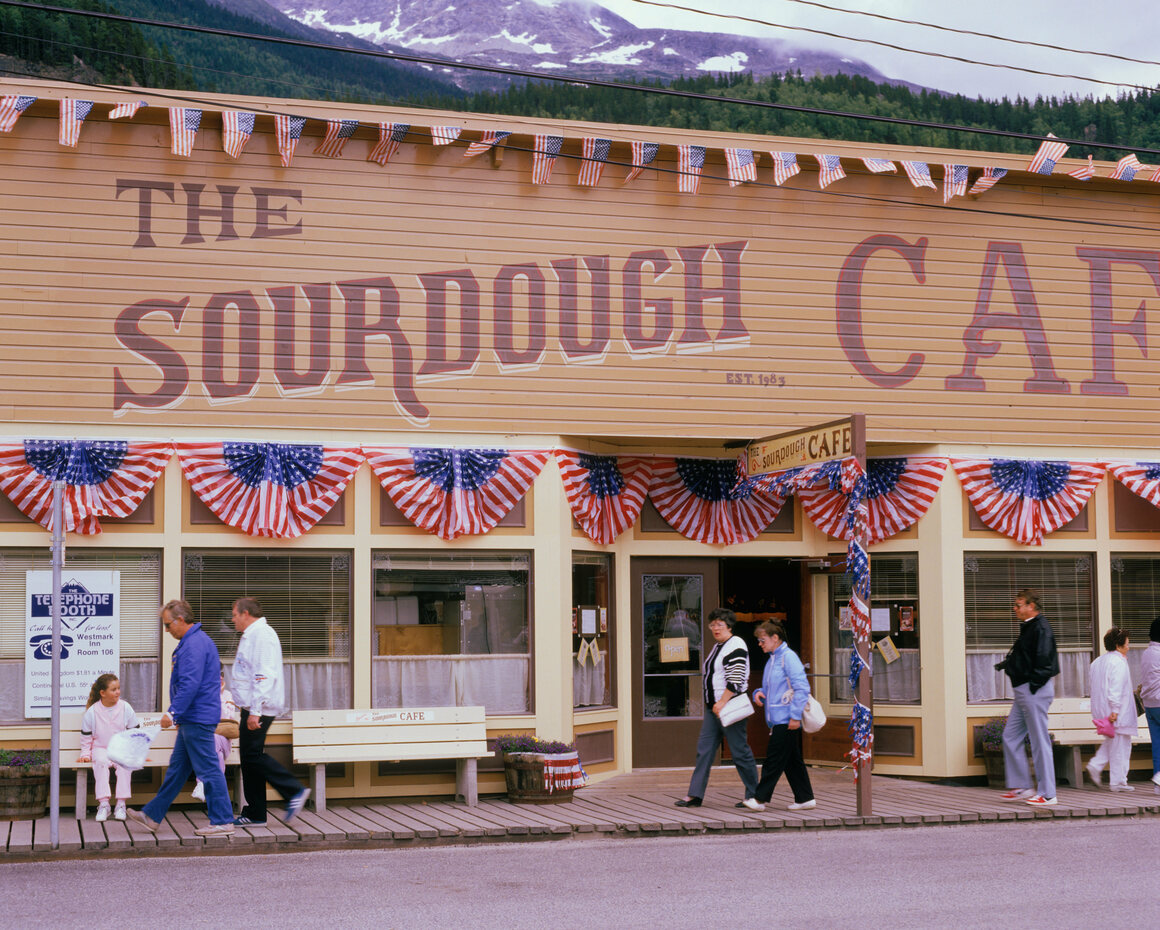

Last spring’s pandemic lockdowns, paired with yeast shortages, produced a sourdough-baking craze around the United States, but in Alaska, the tangy bread has been an important cultural touchpoint for roughly as long as Costello’s starter has been bubbling. Alaskans so identify with sourdough that long-time residents are often called “sourdoughs” and numerous businesses in Alaska use the word to emphasize their experience or longevity, from Sourdough Fuel (heating specialists) to Sourdough Sue’s (yurt purveyors).

“It’s [part of] Alaska history,” Costello says of the sourdough that fed early-20th century newcomers. “It’s the history of all those who came to try their luck at the wilds of Alaska, just surviving off their bag of flour. It’s part of us.”

Historians believe that sourdough is the oldest form of leavened bread, explains Alaska historian Sue Deyoe, and dates back to at least ancient Egypt. While the development of commercially produced yeast and baking soda in the 1800s ate away at sourdough’s popularity in cities, Americans heading west, especially to the gold-rich areas of San Francisco and Alaska, relied on it as a consistent source of food.

“The Canadian Mounted Police refused to let any of the goldseekers over the boundary at Chilkoot Pass [and into Alaska] without a year’s supply of provisions,” writes Ruth Allman, author of Alaska Sourdough (1976). “A 50-pound sack of flour—and a sourdough pot—would guarantee more satisfactory meals than canned food many times its weight.”

Baking other types of bread would call for eggs, milk, and yeast, which were either hard to acquire or unnecessarily weighty for miners hauling all their supplies over mountain passes. With sourdough, though, prospectors only needed to carry flour and gather water to bake bread, biscuits, pancakes, cookies, and more. And a starter that was maintained and fed with fresh flour could remain viable for lifetimes.

“It’s a survival food in a way,” Costello says. “It’s something you had to take care of so it could take care of you.”

While sourdough was adaptable, it wasn’t without its challenges. Sourdough doesn’t like cold weather—Allman wrote of her husband, Jack, who had depended on sourdough in a mining camp, that when he built their cabin in 1949, he first made a shelf near the stove pipe to keep the starter happy, before making a bed or furniture. It’s said that prospectors cuddled their sourdough at night to keep it from freezing. Jack put sourdough in an old Prince Albert tobacco can, Allman wrote, and tucked it inside the pocket of his wool shirt as he went from camp to camp by dogsled.

Over time, sourdough became a sobriquet for those who frequently used it (and often had it on their person, like Jack Allman, in case of emergency), be it the early prospectors or the homesteaders who came to farm as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s. In Jack London’s novel White Fang, the author describes a group of men living in Fort Yukon, Alaska, who “called themselves Sour-doughs, and took great pride in so classifying themselves.” The newcomers, he wrote, were obvious, since they had not yet mastered cooking without baking powder.

Being called a “sourdough” remains an honorific in Alaska. “The character-building experience of surviving Northern winters was a mark of pride among sourdoughs,” writes Susannah Dowds in Alaska Sourdough: Bread, Beards and Yeast. The feat remained challenging through even the 1970s in some remote regions, due to the lack of grocery stores, running water, and electricity. Earning the title “sourdough” today reflects the state’s extraordinarily transient nature: An estimated 50,000 people move to and from Alaska each year, while the total population is around 700,000. Over time it has become shorthand for an experienced Northerner, someone with tenacity, grit, and know-how who has survived untold battles with fickle Jack Frost.

While sourdough fed those in numerous frontier states or regions, Alaska’s lasting relationship is unique. “A perfect duo. The sourdough and his sourdough pot,” Allman wrote. “They have become an important part of Alaska and the historic legends of the North.”

It’s worth lingering on that choice of words: “legend.” Because while sourdough has become part of legends of rugged pioneers braving Alaskan wilderness, it overlooks Alaska Natives who were at home in its far-north landscapes for millenniums before miners and settlers arrived in search of land and gold, and who survived (and thrived) on wild game and harvested vegetables rather than sourdough.

But Rob Kinneen, a well-known Alaska Native chef, says that in the 100 years since, sourdough has become a staple in many Alaskan kitchens.

“I certainly grew up eating it and have cooked with it,” Kinneen says. “It’s definitely become embedded in Indigenous culture, too. It’s kind of like Sailor Boy Pilot Bread: not a traditional food, but something that has been adopted by Alaska Natives.”

Numerous dining establishments throughout Alaska publish the age of their sourdough on the menu. It’s a common belief that the older the sourdough, the better it is. It’s why Costello advertises the age of her supercentenarian sourdough—although verifying its age is difficult or impossible.

Due to the coronavirus, and the fact that Talkeetna Roadhouse serves family-style meals at banquet tables, Costello opted to close the restaurant until the majority of the country is vaccinated. But it remains open to overnight lodgers, and if you ask, Costello will give you a to-go cup of the historic starter to use at home, provided you make her one promise: You’ll do everything you can to keep it and its history alive.