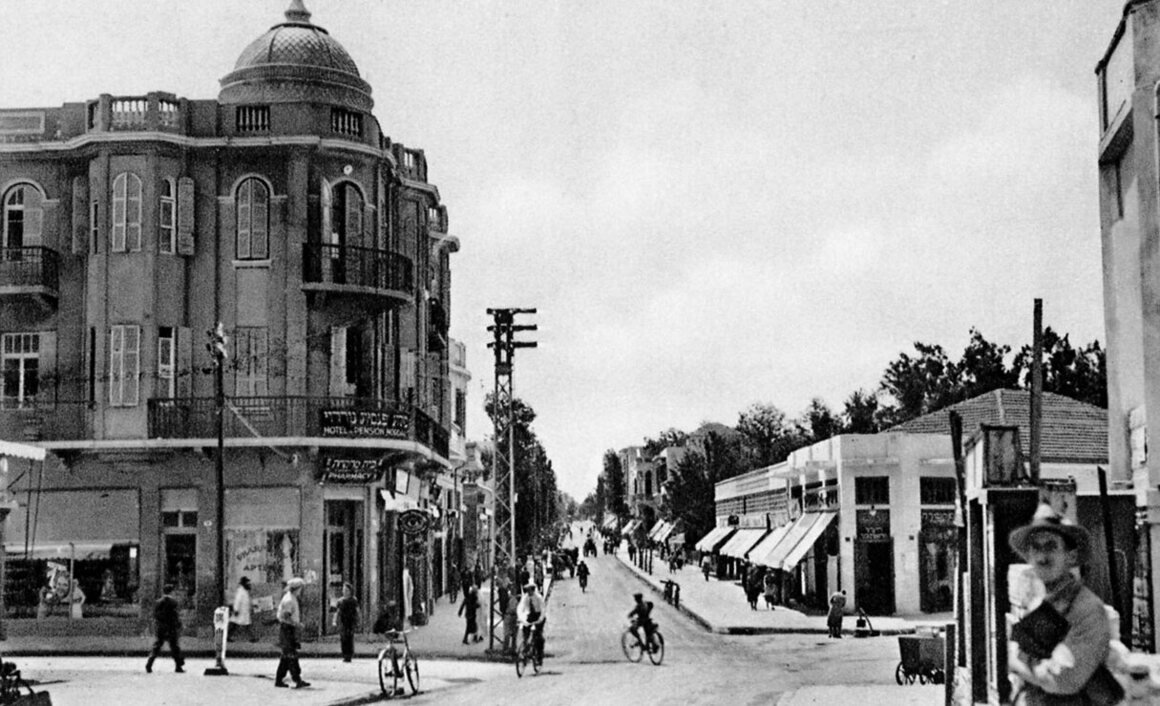

Secrets From Tel Aviv’s ‘Eclectic’ Era Are Hiding All Over the City

Some time during the 1920s, poet Hayim Nahman Bialik took an unauthorized shortcut through the grounds of Jacob Gluska’s construction factory. Gluska’s brother caught Bialik on the property and rebuked him. Bialik, an arrogant Tel-Avivian who was also Israel’s national poet, did not appreciate the remark, and they came to blows.

In 2009, almost a hundred years after the slap that stopped Bialik from taking any more factory shortcuts, Bialik’s home was restored to its former grandeur and opened to visitors as a museum and cultural center. Gluska’s son was the one who recreating its original patterned tiles.

In the early 20th century, Tel Aviv had a distinguished industry of beautiful decorated tiles, which can still be seen in some private homes, apartments, stairwells, and public buildings. After peaking in the 1920s, the tiles have become more and more scarce over the decades. Now, there’s a renewed appreciation for them.

German Christians of the Temple Society sect, who immigrated to Palestine late in the 19th century, were the first to bring the painted tiles to Tel Aviv. But “[d]uring World War II, the British army deported the Templar families to Australia, and that was the end of their involvement in the local tile industry,” says Avi Levi, a landscape architect and hunter of derelict buildings and decorated tiles.

Between 1921 and 1925, Tel Aviv’s population went from 2,000 to 34,000. The new city’s architects were European Jews who trained in art schools in Eastern and Western Europe. Their building style came to be known as Eclectic. Architect Professor Nitza Szmuk, the guru of historical building conservation in Israel, says Eclectic architecture represented “the attempt to create a synthesis between East and West, thereby generating a local notional style.” The architects’ perception of Palestine and the Near East remained Orientalist, even when walking in the Tel Aviv sunshine or buying a tomato at the local grocer. The tiles in their buildings were part of this European Oriental fantasy. In the words of Architect Yossi Klein in a Domus magazine article, “the contrast between ‘the Oriental style’ and the European building technique allowed Zionists to return to a ‘sterile Orient,’ while maintaining European modes of living.”

The European tile workshops developed a wide variety of patterns with floral and geometric motifs, influenced by renaissance, art nouveau and art deco styles, ancient Egyptian art and ancient Greek pottery. The Tel Aviv tile industry mimicked these motifs, but not all of them. Jews and Muslims in Palestine skipped the Christian motifs that were common in the European industry, such as the cross or the lily. Some of the local tile factories, mostly those owned by Muslims, were also influenced by the Moroccan tile industry, characterized by its vivid colors.

“This was the golden age of the painted tile,” says Avi Levi, a landscape architect and hunter of derelict buildings and decorated tiles. “They became a local fixture and the connection to the European origins was forgotten.” The decorated tiles prevailed during the early 20th century in houses in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. They were found in luxurious villas and humble apartments. However, “after three decades, people started to think of the tiles as old-fashioned, expensive and excessive.” Ultimately, “this style flourished only for a short time,” Klein writes, “and as the conflict with the Arab community escalated, Modernist tendencies prevailed.” The romantic, Eclectic style gave way to the clean, modernist Bauhaus. Decorated tiles were abandoned in favor of simple, cheap, industrial tiles. As a result, most of the factories have closed. But at the end of Herzl Street, a street of woodworkers and craftsmen in southern Tel Aviv, the small tile factory of the Gluska family is operating to this day.

Avner Gluska, 82, started working in his family’s Tel Aviv tile factory as a child, with his father Jacob Gluska. Today, he toils there with two workers, using materials and equipment developed 150 years ago. The tiles are handmade, and each worker at the small factory is capable of producing up to three square meters (30 square feet) of tiles a day.

“My grandfather had two wives back in Yemen,” recounts Avner Gluska. “When one of them died, he embarked for Israel with his second wife and his eight children. The family settled in the Yemenite Neve Tzedek neighborhood in Tel Aviv. My father Jacob, who was eight years old, went to work in construction, carrying buckets of clay.” Jacob Gluska worked odd jobs until he opened a factory. In 1936, he teamed up with Abu Khalil Shindy, a Palestinian Arab living in Jaffa, and the pair specialized in tiles. “The Jewish and Arab workers didn’t get along,” Gluska recalls, “so they divided the factory and worked in two locations. My father and his Arab partner were as close as brothers, and we, their children, grew up as one family.”

Some Palestinians were expelled by force in 1948. Many others believed that the Arab armies would retake their towns and villages. They abandoned their homes and left for other countries to wait for victory. The wait became permanent. “Abu Shindy made the biggest mistake of his life: He left everything and fled to Amman,” says Gluska. “This was the moment that destroyed the camaraderie between him and my father. One was furious that the other was leaving him to the mercy of the Arab armies, and the other never forgave the Israeli armies. After the Six-Day War they met again once, for the last time, in Gaza.”

Avner Gluska replaced Abu Shindy at his father’s side, while also studying art. During that time, the factory was manufacturing terrazzo tiles, which became the most common tiles in Israel up until the early 1990s. The demand for painted tiles declined. “The large orders I get today are from house conservation projects,” says Gluska. Over the last two decades, Tel Aviv skyscrapers with doormen in the lobby have lost their popularity in favor of a new status symbol: Historical buildings, restored and renovated at great expense.

Meanwhile, Avi Levi wanders the city, exposing the original tiles. “My love for painted tiles started about 20 years ago,” he says. “My work as a landscape architect brings me to the alleys of Tel Aviv. My love for photography, along with a great fetish for old and deserted buildings, join my love of the first Hebrew city and related nostalgia. So I created a large collection of photographed materials, including tile photos.”

Before Tel Aviv-Jaffa’s 100th year celebrations in 2009, City Hall decided to create a huge carpet of flowers that would represent the city “definitively.” According to Levi, “The brilliant idea came from veteran landscape architect David Skali: Building a huge flower tile, with decorations inspired by tiles and wall paintings from the homes of the founders of Tel Aviv.” Levi, who participated in the project, was sent in 2008 along with his colleagues to a flower carpet laying event in Brussels, to learn how it was done. About a year later, “on the morning of September 16, 2009, trucks unloaded 500,000 begonias, tuberoses and dahlias in Rabin Square, and an hour later, a colorful carpet stretched over 1,250 square meters,” says Levi. “After years of hunting old tiles, it was a mystical moment of closure.”