With No Parade This Year, New Orleans Is Festooned With Mardi Gras ‘House Floats’

For Mardi Gras 2021, when the very idea of a large, tightly packed crowd feels years away, New Orleans has adapted. Instead of floats following parade routes, the city’s artistic verve has turned its attention to dozens of homes and businesses across the city. They’ve been transformed into Bourbon Street–worthy thematic “house floats,” made by artists and everyday citizens. The mood-lifting response to the cancellation of the traditional events also helps support artists who would typically have year-round work preparing the gaudy, celebratory floats for their time in the spotlight.

The concept comes from Megan Boudreaux, a local who jokingly tweeted about making a krewe of her own—membership groups that stage parades and galas for Mardi Gras—after the official cancellation announcement in fall 2020. Her Krewe of House Floats Facebook launched on November 17. So far, 3,000 international members of the group plan to decorate their houses—among them an expat in Dubai—says Boudreaux, who has been named the “Admiral” of the fleet and is decorating her own home as the “USS House Float.”

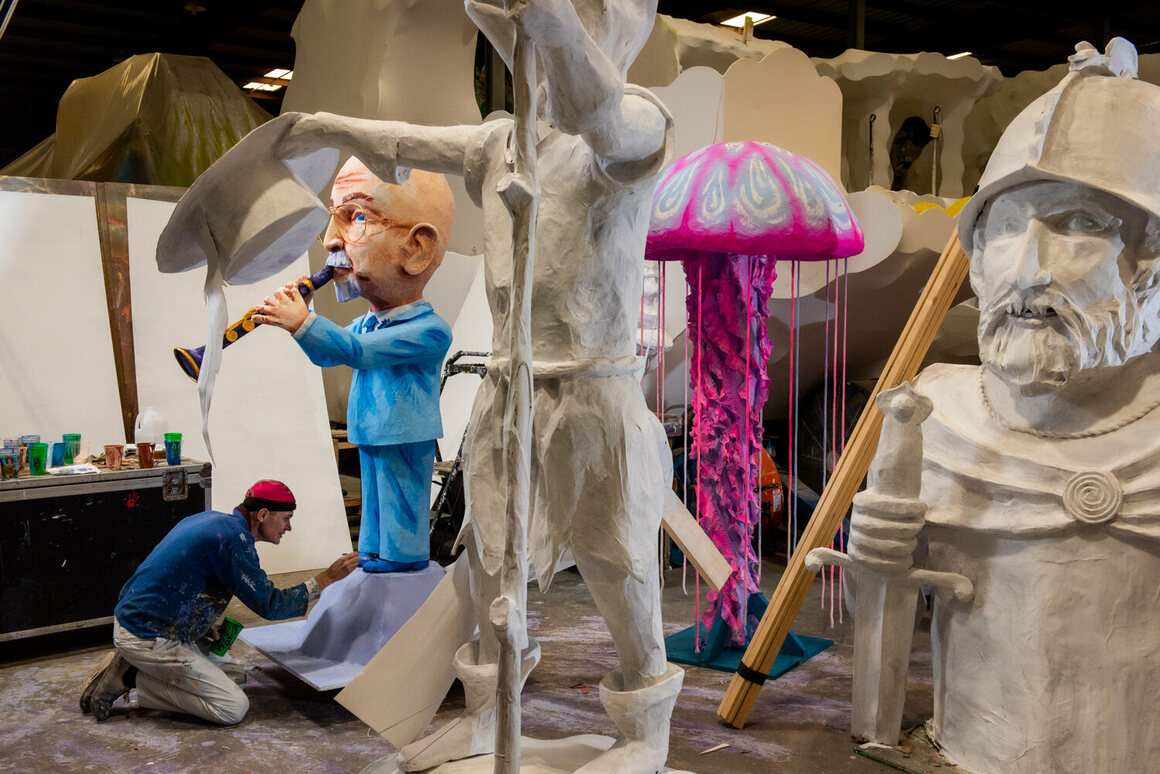

This inspired Caroline Thomas, an artist who designs floats for the Krewe of Rex and Krewe of Proteus (both founded in the 19th century), to launch Hire a Mardi Gras Artist, which is organized by the Krewe of Red Beans. “You can’t imagine New Orleans without the float builders,” says Devin de Wulf, the founder and head of the krewe, which usually stages a walking parade on the eve of Mardi Gras and is named for the dish traditionally eaten that day. “We have to step up and create work for them.”

Thomas and her team of 10 (one of six artistic teams), which she leads as the designer-art director, have so far completed four houses. Forty-five Mardi Gras artists and installation carpenters have been employed to work on 21 sites—“an entire parade” worth of floats, Thomas says—due to be completed by the week before the February 16 holiday. Each takes around two weeks, with entirely handmade elements.

Each house float costs $15,000, and they have been commissioned in more or less equal proportions by individual patrons and a crowdfunding initiative that randomly picks a donor’s home to decorate whenever the target is reached. This model has spread the house floats across many neighborhoods, “so that everybody can feel like they have a little bit of ownership over it,” Thomas says.

When the musician Big Sam of Big Sam Funky Nation shot a music video outside “The Night Tripper,” the first house float, Thomas thought “Oh my God, it’s working!” She had designed the display as an homage to late New Orleans music legend Dr. John.

Jennifer Walner, who commissioned “The Queen’s Jubilee,” designed by Sean Gautreaux, says there is a “non-stop flow” of people coming to see the transformation of her peach-colored Saint Charles Avenue house with pearls, flowers, and caricatures of the family in masks “waving—or maybe trying to catch beads?”from the second-floor balcony.

Many of the house floats’ themes have personal significance for the residents, such as “Acadiana Hay Ride,” an homage to local culture with touches such as an accordion that Thomas designed for a couple who met at a Cajun music festival. There’s also the phoenix that a cancer survivor requested for another float by Thomas, “Mondo Kayo Feng Shui.”

While parade floats go by among crowds and flying beads, the house floats and all their artistic details—such as cypress trees painted on the outdoor lights of the house of “Birds of Bulbancha” (the Choctaw term for the region)—can be enjoyed at a more leisurely pace. Elements must be affixed to houses with the least invasive approach possible—“a few screws here and there,” Thomas says. As a result, a cement house posed particular challenges.

“I think we should really acknowledge this as a valid regional art form and part of our folk culture,” Thomas says, explaining that floats were initially made by theater guilds in the off-season, and that there are techniques special to New Orleans, such as crafting papier-mâché flowers with contact cement on cardboard, rather than using a wire frame.

“A lot of people go through their whole lives in New Orleans without really understanding how these things are built,” says Thomas, who has gotten questions from passersby during installs. The decorations, which will come down the week after Mardi Gras, will have another life at the city’s Contemporary Art Center. There, the artists themselves, usually “hidden away behind the scenes,” and their techniques will be highlighted through process shots from photographers Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee and Katie Sikora, de Wulf says.

The Hire a Mardi Gras Artist initiative could continue even after the traditional parades are back on, says de Wulf. Boudreaux says she has “had a lot of interest [from participants] in doing this again next year.”