Giuseppe Rotunno: 1923-2021

There is an intense polarity at the heart of Italian cinema. On one side is art about the working class and on the other is forbidding, luxurious moving frescos of unspeakable wealth and privilege. Because of this, the cinematographers who were there to coin the language of modernism in the Italian cinema had to become equally adept at filming the intoxicating poetry of the streets, the galvanizing sight of hands performing labor while around the buzz and smoke of productivity a growing consciousness becomes palpable, and, of course, the moneyed chambers of depravity where the richest in the land frittered away their existences. And so a handful of Italian cinematographers became synonymous with film as an art form, from Vittorio Storaro’s ragingly erotic oranges to Mario Bava’s shocks of color and shadow singlehandedly creating modern horror cinema; from Luciano Tovoli’s faithfulness to the textures of modern life to Tonino Delli Colli’s hazy, heady atmospherics. Italian photographers have done more than their fare share of inventing the world. And that is how I would describe the work of the thoroughly celebrated yet still insufficiently pored-over Giuseppe Rotunno. He created the world from nothing, and when he felt like it, destroyed it too.

Rotunno was born in Rome in 1923, and, in his youth, fell in love with photography, working first at famed studio Cinecittà. When the Second World War broke out, he was just old enough to enlist as a newsreel cameraman with the Army. He was only in the field for a short while before Cinecittà recalled him from active service to come home and help shoot Roberto Rossellini’s second feature film “The Man with the Cross” in 1943. Life and the most powerful studio in the country had given him his marching orders and they were louder than those from the state: make pictures.

As Italy put itself back together after the war, Rotunno trained with every major director the country laid claim to. He worked under Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti, Mauro Bolognini, and finally Dino Risi, who promoted him to Director of Photography on 1955’s “Scandal in Sorrento,” starring De Sica and Sophia Loren, whose presence guaranteed him exposure. His second big opportunity was right around the corner when “Sorrento” writer/producer Marcello Girosi and star De Sica re-teamed for American writer Samuel A. Taylor’s (“Vertigo,” “Sabrina”) first and only feature film as director, “The Montecarlo Story.” Rotunno shot in the cinemascope alternative format Technirama, intended to capture the full glamour of the streets of Monte Carlo, where the film was partially filmed. He did this just around the same time he shot the short documentary “Christ Did Not Stop At Eboli,” about the ways in which the lower class of the Italian cinema work to better themselves through improved labor conditions and literacy. Shooting Marlene Dietrich in super 70 mm and filming a news reel about the working poor of Italy in the same six years is a tension that would last through Rotunno’s career, and he was equally good in both registers.

Having made a name for himself as someone comfortable filming the likes of Dietrich, Loren, and Marcello Mastroianni (on Visconti’s “Le Notti Bianchi” in 1957), he would henceforth split his time between international and domestic productions. Rotunno photographed Stanley Kramer’s “On The Beach” (bringing the same sensitivity to the eerie beaches and abandoned cities as he did to bustling Monte Carlo streets), Nunnally Johnson’s final film as director “The Angel Wore Red” (no doubt at fellow screenwriter Taylor’s recommendation), and John Huston’s mammoth “The Bible: In The Beginning … ”, also shot on 65mm. These projects would lead to him being the first non-American allowed in the American Cinematographers Guild, but he wouldn’t become known for his work on these eccentric projects.

No, it was during this period that he would make the movies on which he would hang his career as an image-maker: Luchino Visconti’s ten-year run from “Le Notti Bianche” to “The Stranger,” his first major critical and commercial disappointment. Visconti was born obscenely wealthy, and so he was the director who brought to light in Rotunno’s photography the split between the very poor and the very rich. Rotunno had been an assistant on Visconti’s elephantine beauty “Sense,” one of the great works of operatic cinema, and a landmark of Italian filmmaking. In “Le Notti Bianche,” he turns the streets into a hazy dreamscape, filling Cinecittà with acres of tulle to dim the street lights all over the set, turning the furtive and desperate courtship between Mastroianni and Maria Schell, to say nothing of Dostoevsky’s source novel, into the stuff of purely cinematic romance. They worked together again on the similarly beloved “Rocco and His Brothers” in 1960 and “The Leopard” in 1963. Together the two films account for the bulk of what’s thought of as the great works of New Hollywood. In the silky tapestry of Milanese street life and brute, unbearable masculinity in “Rocco,” and in the magnificently upholstered ballrooms of “The Leopard,” where an aging aristocrat succumbs to the sickness of wealth surrounded by beauty always out of his reach, Visconti and Rotunno coined a language that would feed “The Godfather,” “Raging Bull,” “Mean Streets,” and dozens more.

In essence, the American cinema we know today starts at Cinecittà. To give you some indication of the combined impact of director and photographer, consider that Rotunno’s future employers would include Alan J. Pakula, Mike Nichols, Arthur Hiller, Bob Fosse, Monte Hellman, Robert Altman, Richard Fleischer, and Sydney Pollack. Rocco’s collection of impeccably expressionist black and white compositions seem to draw the emotion from its sprawling cast. “The Leopard” is like some holy fusion of Caravaggio and Titian, an enormous canvas on which is painted warfare, celebration, love, death, and the illusion of prosperity. And yet the film’s most powerful image is a series of close-ups as Burt Lancaster’s Prince Don Fabrizio Salina stands almost motionless and feels his mortality creep over him for the first time.

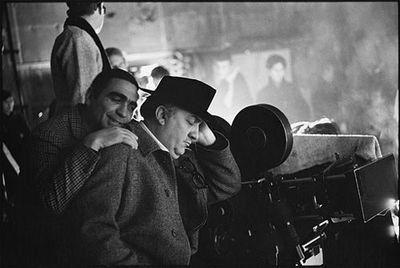

Of course, some of those movies also owe a debt to the work of Federico Fellini, who had become a sort of celebrity director for putting his own neuroses and infidelities on screen and was about to enter a new phase of his career. At the moment, just before the third act in his career, his regular photographer Gianni Di Venanzo died suddenly at age 45. Visconti released Rotunno from his employ after the box office failure of “The Stranger” and a new and powerful working relationship was born. When people talk about “Fellini,” or “Felliniesque,” the word that has come to stand in for the carnivalesque and colorfully obscene, they mean less his modernist leaning ’60s work, or his magical ’50s tragicomedies. They mostly mean the absurd and deformed picaresques of the ’70s and that is due in large part to Rotunno stepping into the breach with him.

As Fellini became a brand like Warhol, Rotunno dug deeper and deeper into his director’s obsessions and his past to create a new kind of fabulously grotesque experience. In “Satyricon,” they weave a tale of the start of culture and eroticism in cavernous sets, paving the way for the idea of cinema by filling Platonic caves with shadows of sex, dependency, betrayal, and ultimately destruction. In “Roma,” they reconstruct the busy city of both men’s youth, creating a place part monotonous purgatory, part barely glimpsed heaven, and all delectably sinful hell. In “Amarcord,” they reconstruct the moment in history just before the renaissance of Italian cinema, showing moments of gleefully lost innocence and collective, communal rediscovery of the same.

Rotunno would be hired by Terry Gilliam for “The Adventures of Baron Munchausen,” by Robert Altman for “Popeye,” and by Bob Fosse for “All That Jazz,” among others, to recapture the demented but gorgeous atmosphere of his work with Fellini. As a consequence, those three particular films remain, arguably, their creators’ best work when judged purely on aesthetic/cinematic terms. Rotunno worked for years with directors as disparate as Sergio Corbucci, Ivan Passer, Lina Wertmüller, and Salvatore Samperi, working more as a conduit to a less ostentatiously presentational style. It was, in those cases, more as if he were providing backdrops for the readings and interpretations of great novels.

His final film was for Dario Argento, and 1996’s “The Stendhal Syndrome” has a muted palette and a non-confrontational camera, something as close to a calm as Argento’s cinema is capable. The movie’s plot concerns a woman who, as the title implies, literally loses herself in art. It was the perfect fiction film upon which to call it quits (his proper retirement, followed by years of teaching, came the next year after working on a documentary about his lifelong friend Mastroianni, who’d just passed away). They let the beauty of the film’s myriad scenes of art be filled with world famous works of Italian art, the streets of Rome where he cut his teeth as a photographer and discovered his life’s passion, and of course, in the studios at Cinecittà, where he first created his living, breathing cinematic art.

Giuseppe Rotunno gave us all the gift of modern cinema when he looked through his viewfinder and into light, in effect guiding us out of a cave and into a world he created. Whether through showing the aching hands of Monicelli’s organizers, the bruised faces of Visconti’s brothers, or the towering and bizarre Eden of Fellini’s world of nightmares and erotic dreams, he became synonymous with Italian cinema, and he made it immortal.