The Serendipitous Survival of Soccer’s Least-Known Birthplace

On March 11, 2017, Graeme Brown brought a GoPro on a journey through time. It was a short walk, about a third of a mile, but encapsulated nearly 150 years of history. Starting from Hampden Park, the current home of Queen’s Park Football Club and the Scottish national soccer team, Brown headed to Cathkin Park, which once was the second Hampden Park, and finished the walk at Hampden Bowling Club—under which, it seems, lies the first Hampden Park, where soccer as we know it today was born.

Hampden Bowling Club is an inconspicuous one-story building that presides over a green in south-central Glasgow, next to a rail line. It’s one of 10 lawn bowling clubs in a square-mile tranche of the city, but it’s the only one with a peculiar claim to fame—and it’s where passionate history buffs and Scottish soccer fans are cheering excavations scheduled for summer 2021. The archaeological efforts slated for the club’s lush green are a collaboration between Archaeology Scotland and the Hampden Collection, an historical, ‘football’-focused effort to commemorate the Hampden Parks and their shared history. “The whole point of this project is to change the way people think about football…It is so much more than just a game,” Brown says. “In fact, 95 percent of football is not about 90 minutes, but everything that goes around it.”

When Brown, who’s worn many titles in his time at Hampden Bowling Club, first joined the then-floundering club in 2011, it was losing older members without replacing them with new blood, and looked fated to close. Brown did what he could to rally the community around the club, and it worked—but it wasn’t until 2016 that he learned just what he had saved. That’s when one of the club’s old guard told Brown that the bowling club’s humble home was once the pavilion of Queen’s Park Football Club, one of the oldest association soccer teams in the world and pioneers of the “pass-and-run” style of soccer that came to define the sport, moving it beyond the rough-and-tumble rugby-like style of play that preceded it. Brown realized that if the club truly sat on Queen’s Park’s old ground, an important piece of soccer history was going uncelebrated.

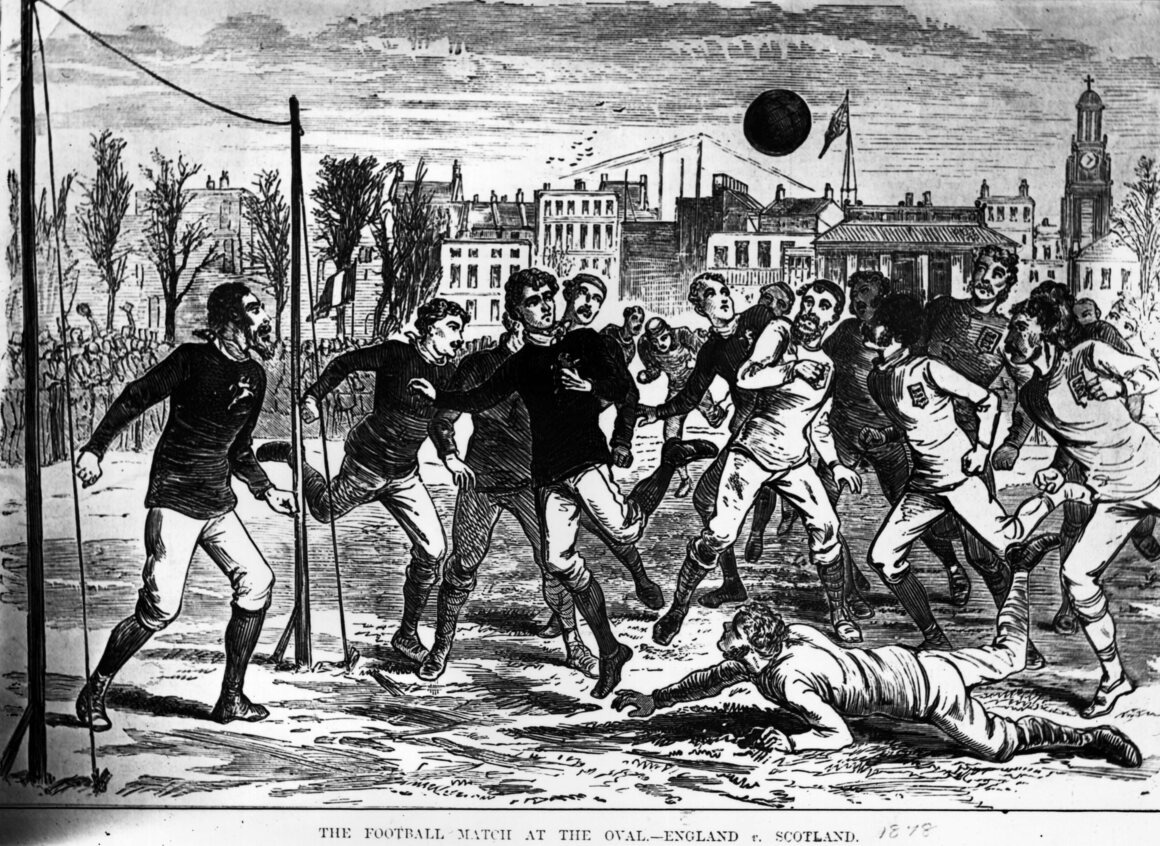

Scottish soccer is big today, but when the Glaswegian bowling club was founded in 1905, it was king—even if the rules were still in flux. In the 19th century, soccer was an amorphous game, governed by different associations with rules that varied by match. Up until 1863, goal widths varied by venue; height specifications on goals weren’t codified until 1882, according to FourFourTwo, a soccer magazine named for a common squad formation. By the turn of the century, Glasgow was home to the three biggest football grounds on the planet: Ibrox, Celtic Park, and Hampden Park, the latter of which was the 3rd iteration of Queen’s Park FC’s stadium, and which was the shared home stadium of the Scottish national team.

When Brown was told of the purported historic site the bowling club now occupied, he went looking for answers. The truth was muddied by Queen’s Park FC’s many movements over the years: To make way for a rail line, the team moved across the road from first Hampden, building second Hampden in what is now Cathkin Park. They took the pavilion building with them when they left, though when Queen’s Park moved to the current Hampden Park, the pavilion was brought back to its original site, for the bowling club to use. After a year of searching for a map proving the location of first Hampden, Brown got word from the National Records of Scotland archives that staff had sent a map to the bowling club’s letter box. It arrived on March 11, 2017, the day of Brown’s walk of the Hampden Parks, and the 135th anniversary of Scotland’s victory over England on the ground.

The map confirmed what had become an old wives’ tale at the club—that they sat on the location of first Hampden, the first soccer stadium built for international competition; where one of the first crossbars was added to soccer goals; where the Scottish national team trounced England more than once, and famously in 1882 by a margin of 5 to 1; where the first professional Black soccer player, Andrew Watson, perfected his legendary game; where soccer’s season ticket debuted.

Archaeologists will dig several excavation trenches on the perimeter of the bowling green and around the clubhouse, in the hopes of finding the detritus of long-ago soccer matches—buttons from clothing, coins from entering the stands or purchasing concessions—as well as the possible rubble foundations of earlier structures. The bowling green will not be physically disturbed, but researchers will use ground-penetrating radar to see if any of the original pitch remains.

In previous surveys, researchers have been able to look for signals specific to the chalk outline that would have marked the borders of play. “This would have accumulated over the years and stands out in contrast to the background noise of the rest of the playing surface,” writes Paul Murtagh, a senior project officer with Archaeology Scotland, via email. “It will depend on how much of the original playing surface survives below the ground—we won’t know until we start.” Researchers sometimes find evidence of structures and schmoozing, too. At Cathkin, where there has been little development, Murtagh says, they found buried remains of demolished buildings, as well as glass and china around a former pavilion where players and staff socialized.

“To find the center spot of the first purposefully built football stadium in the world…that’d be worth a monument or two, I think,” Murtagh said at the recent town hall.

Brown says the work is bigger than the sport, or what the sport means to Scots or Glaswegians. It’s about how the spit of land buried in central Glasgow gave rise to a phenomenon played, watched, and appreciated the world ‘round—and ensuring its preservation. “What it comes down to is, ‘How on Earth could Scotland lose its most important football ground? How could it do it?’” Brown says. “And most importantly, [how can we] never let that happen again?”