How a Korean-American Farmer is Sharing Her Heritage Through Rare Seeds

Farmer Kristyn Leach wants to talk about her delicious harvest from last year. “Progress is good,” she tells me. As it happens, that’s a huge understatement. Kitazawa Seed Company, the retailer that sells Leach’s heirloom seed varieties, reports that sales are up tenfold.

“Her seeds are just flying out the door. It’s pretty phenomenal,” says Maya Shiroyama, Kitazawa’s owner. “When she drops off her seeds, within a few days, we have to reorder.”

But this was no overnight success. Since 2012, Leach has worked the land on Choi and Daughters, her tiny, 2-acre farm in Winters, California. The farm has become a one-stop-shop for Bay Area chefs, farmers, and gardeners seeking to grow vegetables and herbs native to Korea and East Asia. These days, Leach is hailed as one of the latest leaders preserving the 150-year legacy of Asian-American farmers in Northern California.

Born in Daegu, South Korea, Leach was adopted into a blue-collar, Irish-Catholic family in New York. At an early age, she gravitated towards her grandmother’s massive garden and toiled in local community plots. Her farming days continued into adulthood, and she soon found herself across the country, bouncing around farms up and down the West Coast. While interviewing for a farming job in Bolinas, California, Leach met her mentor, the farmer Dennis Dierks of Paradise Valley Produce.

The two quickly bonded over their admiration for Korean natural farming, a sustainable practice that uses indigenous microorganisms to enrich the soil, rather than herbicides or pesticides. Dierks had first heard of the practice from a Filipino teacher, while Leach knew of it from studying her Korean heritage. Working with Dierks, she reflects, “was probably the best step for me moving towards having my own farm.”

It wasn’t long before she decided to put down roots in Northern California. The Bay Area, with its diverse and large Asian-American population, offered the perfect ground for Leach’s eventual dive into Korean seeds. In fact, Leach is just the latest in a long line of Asian-American agricultural trailblazers, many who have made the area their home since the mid-19th century.

Asian-American farmers have played an integral role in the history of farming in America, especially in California. As news of the Gold Rush spread in 1848, Chinese immigrants flocked to Northern California. Some immigrants opened up laundromats and restaurants, but those from the Pearl Delta Region in China, an agricultural hub, began growing working on local farms as well as growing vegetables and fruits in their mining camps.

However, the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 halted most immigration from China, and also hobbled the West’s growing agricultural industry. Farmers from Japan, Korea, and the Philippines flocked to the Bay Area to fill the void. Like the Chinese farmers before them, they introduced their ancestral farming techniques and seeds to the California community. Today, the legacy of these farmers endures in modest multi-generation farms and businesses such as Kitazawa.

The Oakland-based Kitazawa Seed Company, America’s oldest company specializing in Asian vegetable seeds and the world’s largest distributor of Asian seeds outside Asia, is one such business. In 1917, Gijiu Kitazawa started selling seeds out of a San Jose warehouse. His business, which offered an amazing spread of domestic and Asian vegetable varieties, grew to rival local retailers who only sold a handful of popular seeds. When the American government during World War II forced him and the majority of the country’s Japanese-Americans into internment camps, the business shuttered for nearly three years. But after the war, Kitazawa bounced back with new energy. In order to reach customers scattered across the country, he began shipping seeds out of state, and soon enough, the company gained a devoted clientele that still exists today.

So once Leach moved to the Bay Area, Kitazawa inevitably appeared on her radar. As an adoptee who didn’t encounter much Korean culture as a child, Leach marveled over Kitazawa’s elegantly illustrated catalog, with its images of springy amaranth, bright yellow melons, and hearty turnips. Eager to test out Kitazawa’s seeds, she placed her first order, 10 years ago, for Korea perilla.

Even now, Shiroyama, the current owner of the company, remembers that order. “At the time, we were selling very few types of Korean vegetables,” Shiroyama says. “Her order definitely focused on that so it caught my eye.”

After her first encounter with Kitazawa, Leach wanted to try cultivating her own Korean seed varieties. Already a loyal customer, Leach struck up a partnership with Shiroyama and produced a batch of Korean chili pepper seeds for the retailer. Today, she continues to add new seeds to the Kitazawa catalog through her seed preservation collective, Second Generation Seeds. Local demand is higher than ever for Korean seed varieties, and Shiroyama and Leach have since become business partners, confidants, and huge perilla fans.

On the phone, Leach lights up when talking about Korean perilla, which is still her favorite plant to grow. Many home gardeners seem to agree: it’s one of her best-selling seeds at Kitazawa. Perilla is a leafy green herb with a sharp flavor often likened to anise and licorice. In the Korean kitchen, the plant transforms into a delectable pickled side dish or a refreshing wrap for barbecued meats.

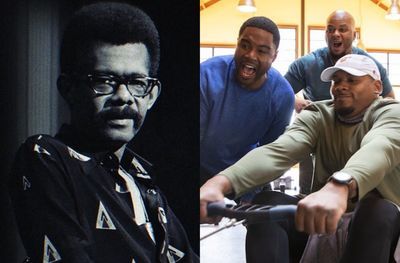

Leach’s perilla experiments opened the door for more collaborations, this time, with the second-generation Korean American chef Dennis Lee of Namu Gaji, a San Francisco restaurant group run by Lee and his two brothers. “She walked in our front door with perilla, and of course we were super excited,” he says. “I know it was love at first sight.” With guidance from the Lee brothers, Leach started funneling more Korean and East Asian vegetables from her farm straight into Namu kitchens.

Whether it’s bright red chili peppers, yard-long beans, or sweet chamoe, or Korean melon, Leach finds joy in cultivating seeds that connect people with their heritage. While giving tours of her farm, Leach sees visitors experience nostalgic memories all the time. “When you see people stop and turn on their heel because they’re so happy to see or reunite with a plant,” she says, “their reaction is definitely the most rewarding.”

Leach herself has jumped at every chance to experience her own Korean culture. In 2015, Leach flew to South Korea with a mission—to learn all that she could about natural farming techniques from the experts. Her journey led her to farmers and and heirloom crop preservationists who bestowed her with a collection of seeds. Enamored by the sustainable farms in Korea and equipped with a new batch of mentors, Leach flew back to California determined to grow and distribute “a lot of those crops, because they were attached to such interesting stories.”

Some of her seeds are prized for what they can produce, such as the wildly prolific Lady Hermit pepper, bred as the ideal basis for fiery gochujang paste. Others, Leach treasures because of what they represent, such as the Sagwa chamoe apple melon. Largely supplanted by other varieties during the Japanese colonial era, these tiny, ancient melons are championed as a truly Korean specialty.

With nearly a decade of momentum behind her, 2020 nevertheless was a challenge for Leach and her farm. News of the pandemic in early March shook up her produce orders for restaurants. Then terrifying California wildfires in late summer created eerie orange-tinted skies above her fields. During this time, Leach brainstormed multiple new business models to keep her operation afloat. The farm introduced Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) boxes, dished out invitations to virtual potlucks, and launched a series of educational farming activities for children.

But it’s her seed preservation business that’s taken off. In quarantine, people are seeking control over—and meaning from—their food, often in the form of home gardening. “One customer wrote us a comment saying, ‘Thank you for caring, Second Generation Seeds. It’s about time someone sold us some relevancy,’” Shiroyama recalls. “Of course that was an extreme compliment to Kristyn. People who are experienced gardeners definitely want to try new things and be challenged as well.”

As she reflects on 2020, Leach looks to her eight-month child to reaffirm her purpose on the farm, especially her long-term investments in sustainable farming practices and seed preservation. “I’m hoping that when she’s old enough to stand and I’m telling her what the year she was born was like, she’ll tell me, ‘Wow, I can’t even imagine a world so insane and so terrible,’” she says. “And I’m thinking about what it is going to take to get there.”