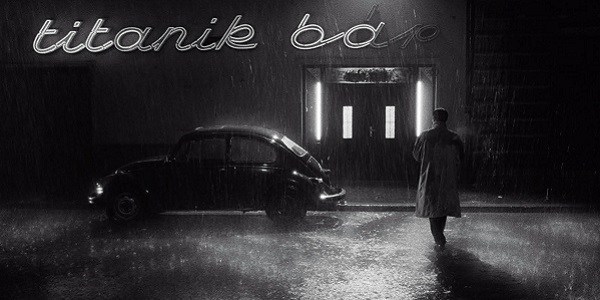

When the Jersey Shore Was the Epicenter for Haunted Attractions

Turn on any television in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, or New York during summer in the early 1980s, and you were likely to catch a commercial featuring a creepy mime trapped behind an invisible wall, the shadowy figure of a hunchback rounding the corner of a darkened staircase, and a headless woman swatting away the attentions of a handsy mad scientist. The organ sounds of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor played hauntingly in the background, while an amorphously accented voice described a series of horrors. Then came the kicker: “Brigantine Castle … it’s ALIVE!!”

Brigantine Castle was just one of the haunted attractions that dotted the Jersey Shore in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when boardwalks and amusement piers from Wildwood to Asbury Park were brimming with families, couples, and teens (and before the reputation of the Jersey Shore evolved to include a particular species of hedonism), drawn by more than sandy beaches, carnival rides, and funnel cake. Months before Halloween, they also wanted to be scared out of their wits. In fact, these purpose-built, walk-through “houses of horror” left indelible impressions on kids like me. Unlike dark rides, such Disney World’s Haunted Mansion, these attractions were staffed in large part by student actors who loved theatrics and makeup, and knew how to improvise. They also operated at a time when laws were much less strict and liability seemingly less of an issue. This meant that if you encountered, say, the castle’s “butcher” and he was carrying a knife, that knife was most likely real. Anything went, anything was possible. So these places soon became legendary.

Perched atop a renovated amusement pier in the coastal city of Brigantine, just northeast of Atlantic City, Brigantine Castle was the first of its era. This ominous-looking, five-story attraction overlooking the sea opened to the public in late May 1976, and is said to have drawn a million visitors annually during its heyday. It was an instant hit among adults and teenagers alike, including a then-14-year-old New Jerseyan named Paul Spatola.

“My older brother Mike was a makeup artist at the castle,” Spatola says, “so I started hanging around there too.” Spatola soon became the castle’s youngest staff member, earning the nickname “wolf puppy.” He joined a cast of costumed characters that included reputed ax murderer Lizzie Borden, a version of Psycho‘s Norman Bates, and Lucifer, the devil himself.

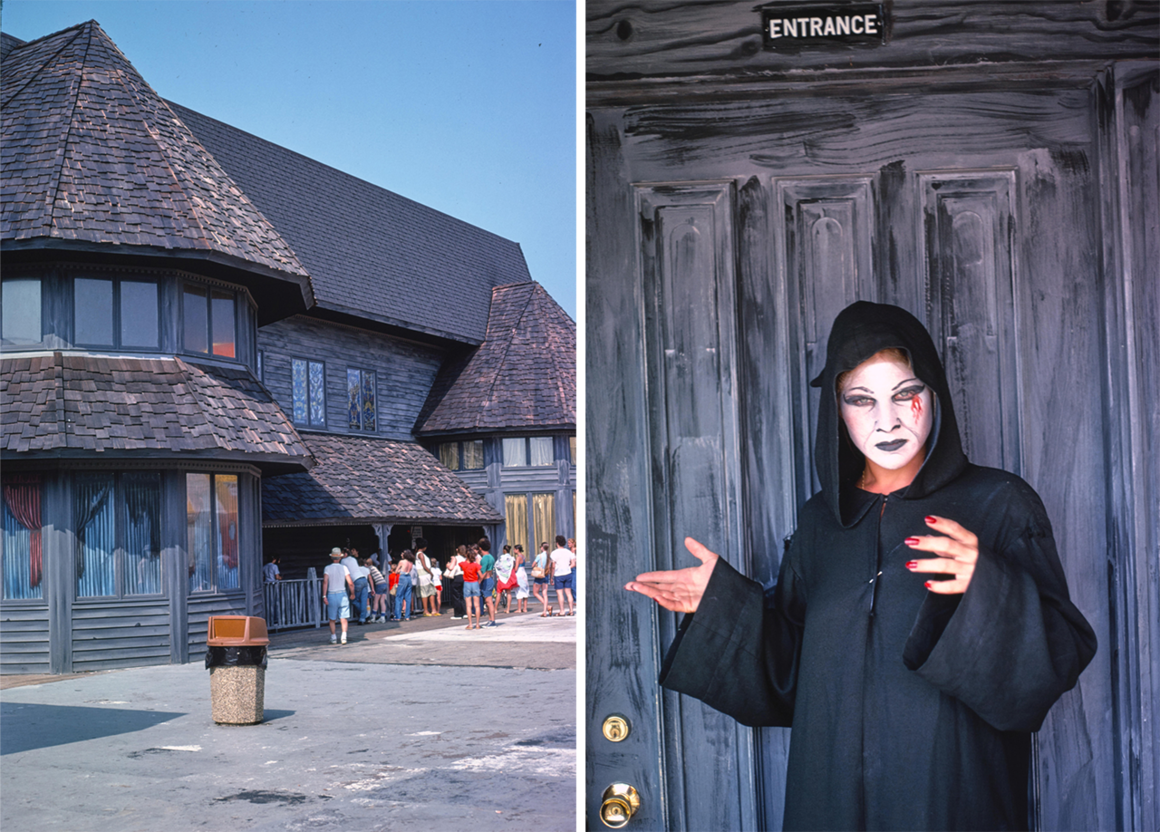

From outside, the dull gray fortress of Brigantine was menacing—quite a contrast to blue skies, crashing waves, and tumbling beach balls. You could often see the castle’s demonic-looking cast hanging around the backdoor, and watch fathers daring their teens to enter, then cringe as they handed over their tickets, fear in their eyes. I had never gone in myself, but I knew the real frights were inside. Patrons found themselves in a darkened maze of approximately 30 rooms, each with its own blood-curdling storyline.

In the rat room, dozens of screeching “rodents” scurried against visitors’ feet: a trick pulled off with rubber hoses attached to the wall and topped with fuzz, while recorded rat sounds were pumped at full-volume over a loudspeaker. The tilt room featured slanted floors so that patrons would fall toward the wall when they entered, a scare made more menacing when the staff turned off the lights. There was also Satan’s banquet, a feast attended by the life-size mannequins of terrors real and fictional: Henry VIII, Genghis Khan, Hitler, Vito Corleone, someone from Planet of the Apes, and more. According to Spatola, now a slot technician in Atlantic City, “The devil sat above them on a shelf, overlooking the entire table.”

Spatola enjoyed portraying the castle’s more physically oriented characters, such as the werewolf and any number of monsters that appeared in the Castle’s plaza room (“Because you could go crazy in there,” he says), there were also plenty of speaking roles. These, he says, were often the domain of acting students on break from nearby schools such as Stockton State College (now Stockton University) and Atlantic Cape Community College. Spatola’s brother, Mike, spent summers at Brigantine Castle honing his skills in makeup artistry, attaching dangling eyeballs and protruding horns to co-workers’ faces daily. In fact, he made a successful, award-nominated career out of it.

Popular as it was, it didn’t take long for Brigantine Castle to inspire others, most notably a sister attraction, the Haunted Mansion in Long Branch, 85 miles to the north. Opened in 1978, the 10,000-square-foot mansion shared many of the same themes and employees, as well as the footage used in commercials. Brigantine Castle owner Carmen Ricci even had a stake in the mansion for a time. The biggest difference between the two was accessibility: Brigantine Castle was all sharp corners and staircases, while the three-story Haunted Mansion had ramps.

Lillian Grauman worked at both Brigantine Castle and Haunted Mansion. She started at the mansion right out of high school, and found herself managing the attraction by the time she was 19. “It was a lot of responsibility,” says Grauman, a crew manager for the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and an independent operations professional who organizes concerts. “There were at least six bars on the amusement pier that housed the mansion, so after about 9 p.m. or so you’d have a whole different crowd than from earlier in the day. Long Branch also attracted more New Yorkers, while Brigantine was more of a Philly crowd,” she says, “meaning things were a little bit rougher in Long Branch.”

The tales of these places are endless. There was the time when an off-duty New York City cop dropped a gun from his ankle holster while walking through the mansion. “We were all running around trying to find this gun in the dark,” says Grauman, “while people were still walking through. Thankfully we found it in an area where there wasn’t a lot of pedestrian traffic.” Then there was the day that Brigantine’s sprinkler system accidently activated. “I was in full-costume, picking up kids and running with them,” Spatola says, laughing. “I thought the fire was real. Meanwhile, all they’re thinking is, ‘Ahhh, the monster got me!”

Farther south along the Wildwood boardwalk stood Castle Dracula, which opened in 1977 and included both a walk-through portion and a dungeon moat boat ride. The castle paid homage to classic horror figures—its namesake, Frankenstein, the Mummy, the Phantom of the Opera—and for the performers, interacting with patrons was part of the fun. “We used to make gallons of our own stage blood and we’d keep it in the front room so that we could use it throughout the day,” says David Miller, who says he played every role under the sun at the castle each summer, from the late 1980s until 1994. “We’d often come out in costume with a mouth full of blood and spit it at visitors, claiming that ‘Humans are disgusting,’” says Miller, now a life coach and reiki master. “This is how we introduced ourselves and set the tone. It’s what made it so exciting for people.”

Thayne Tessenholtz, who took on the role of Lizzie Borden at Long Branch’s Haunted Mansion in its inaugural year, agrees. “We always had a good time playing with the clientele,” she says, “especially when they played back.” The actors at all three attractions were basically given carte blanche with their characters and storylines, and the more authentic the scare, the better. Like when they’d overhear a patron’s name and then pass on, so that characters like “The Zombie” or “Rat Professor” could then single that person out directly. Or utilizing the secret doors in the Haunted Mansion, as Tessenholtz often did, so she could loop past the same group of people. “I’d be wearing a black shroud with the hood up, and mumbling ‘Let the witch go by.’ It was even freaking out some of the employees,” says Tessenholtz, now retired.

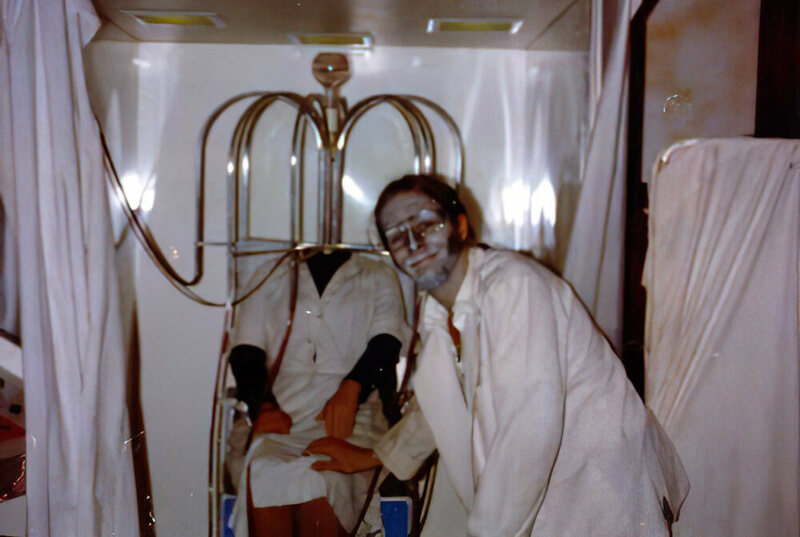

Then there were the optical illusions. Some were used sparingly, such as Brigantine’s werewolf, in which a regular performer would transfer into a wolf-like creature right before patrons’ eyes. “It was a little difficult to do,” requiring three people and a trick of light and mirrors, says Tessenholtz, “so we saved it for VIPs.” Others, such as the Mansion’s Jack the Ripper (who created the illusion of chopping off another performer’s head and then placing it on a table, achieved with dark lighting and black velvet cloth), were more regular features. But the illusion most beloved among visitors and despised by employees was the headless woman, one that was used frequently at both Brigantine and the Mansion.

“It was the absolute worst,” says Grauman. “You had to sit in a chair with your neck back, and it was so uncomfortable.”

“There were mirrors positioned accordingly so it looked like the person didn’t have a head,” Tessenholtz says. “But you still had to interact with the patrons as they came by.”

Spatola agrees. “It got to the point where women were refusing to do it,” he says, “so we had to use smaller men instead.”

Although most of the employees at all three attractions performed a variety of roles, and did so with zeal, there were certain people who stuck to what they were good at. “Our Frankenstein really only played that role,” says Tessenholtz. “But he was also six-foot-nine and then wore five-inch platform shoes, and he had that stocky Frankenstein build. It was perfect for him.” Among these more dedicated performers, there were also a small percentage of employees who saw haunting as nothing more than a summer gig, just a bit of extra cash. “We’d call them the dungeon rats,” says Miller, laughing, “because we’d sentence them to work in the bowels of the castle all summer.”

It was greater cultural currents, and not a bunch of lawsuits, that eventually doomed the attractions. With the rise of slasher films—Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street—scaring people with a low budget and more traditional characters became more and more difficult. Not to mention that the structures themselves weren’t exactly built to last. “Everything was constructed out of wood and stucco,” says Miller. “So as the years went on their interiors would completely dry out, making them all highly flammable.” In fact, all three attractions eventually went up in flames, though thankfully no one was hurt.

A gas and electrical fire destroyed Long Branch’s entire amusement pier in June 1987. Brigantine Castle, though already closed and slated for demolition, went up in flames a few months later. Castle Dracula lived on until 2002, when it became the victim of arson. None were rebuilt. “There’s too much liability these days,” says Grauman.

The attractions, however, live on as fierce nostalgia, particularly in Facebook groups and the occasional reunions. “With enough money, I guess you could recreate anything,” Miller says. “But the people and the way that we worked together? That would be really difficult to replicate.”