This Project Maps 25 Years of New York’s Lesbian Nightlife

When Jen Jack Gieseking started researching his book on queer nightlife in New York, he learned that one of the city’s hottest lesbian watering holes was not a bar at all. Sure, participants had fond memories of dancing and flirting at historically lesbian bars. But if the queer women and transgender and nonbinary people in Gieseking’s focus groups really wanted to catch up on the latest gossip, there was only one place to go: the Park Slope Food Co-op, a collectively owned and operated grocery store in Brooklyn.

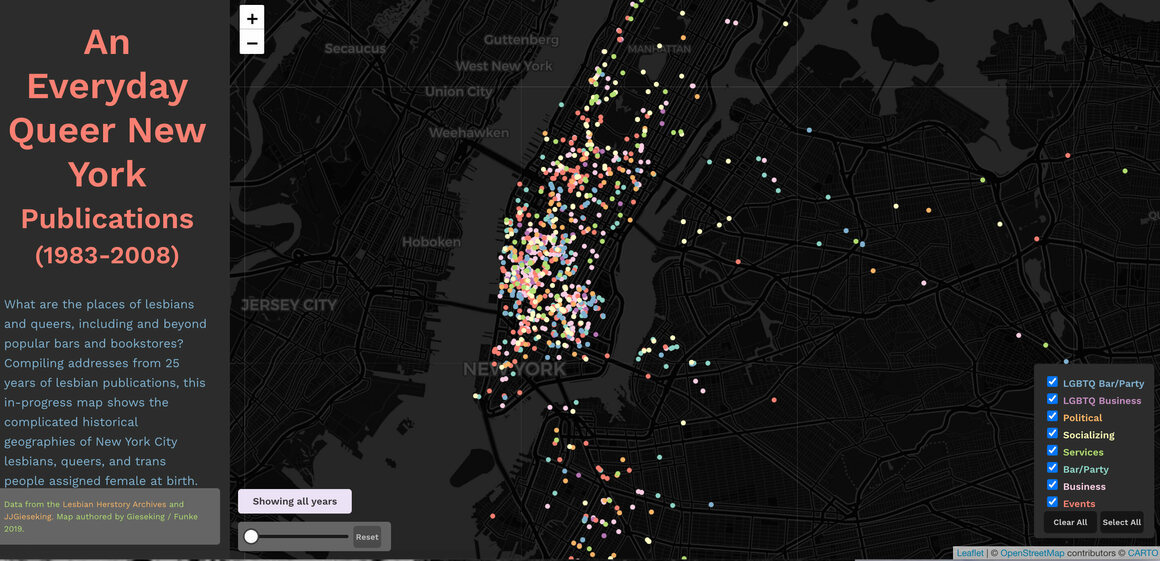

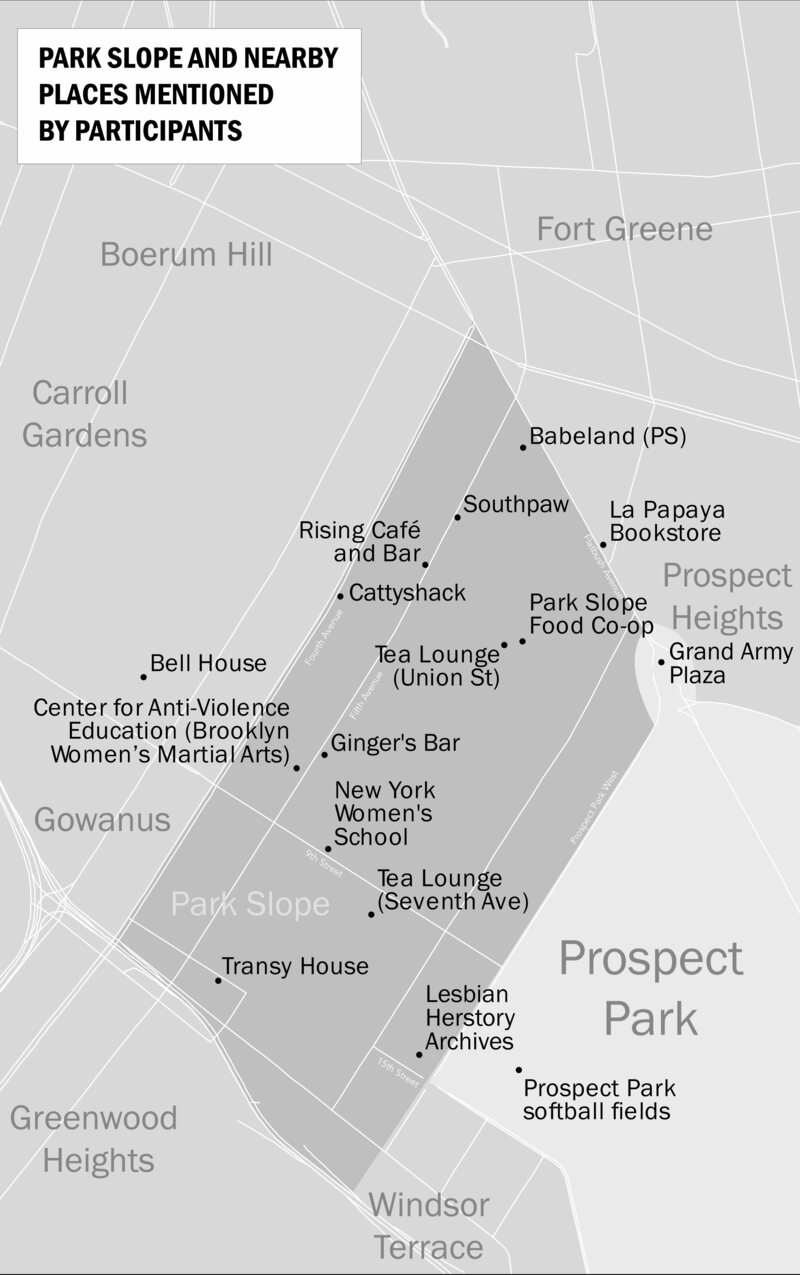

“Amusingly, participants frequently preferred to gossip about goings on at the Park Slope Food Co-op rather than bars,” writes Gieseking, who himself joined the co-op in the 2000s hoping to meet someone. While the co-op is known for its leftist politics and neighborly infighting, it’s not explicitly lesbian. Yet it’s just one of the many unexpected spaces that Gieseking includes in A Queer New York, a book and collection of interactive digital maps that chart 25 years of New York City’s lesbian, transgender, and gender nonbinary social spaces.

To research the book, Gieseking interviewed dozens of queer women and trans people who came out between 1983 and 2005. He also spent countless hours digging through the Lesbian Herstory Archives, a queer women’s archive in Brooklyn, and noted down every advertisement and mention of queer parties, restaurants, services, and events.

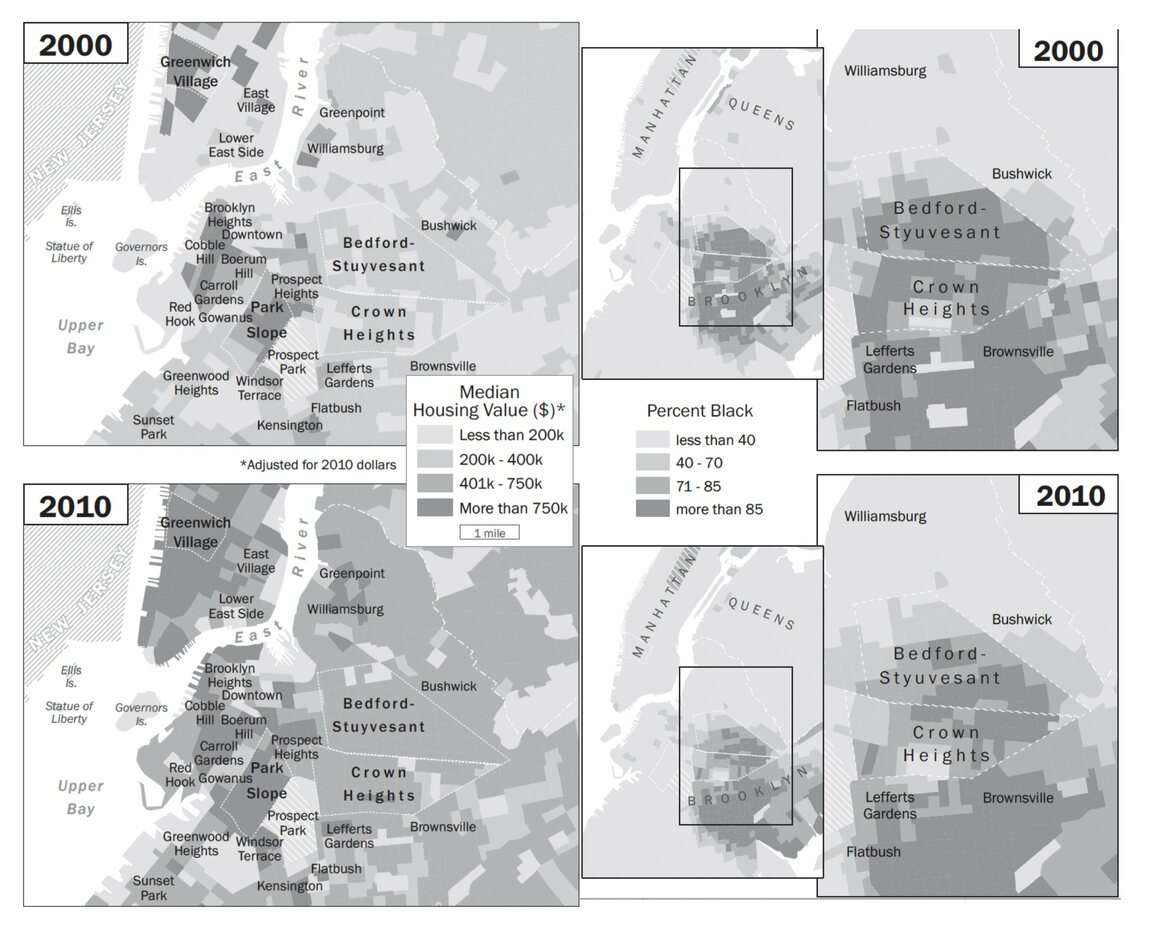

Gieseking, an Assistant Professor of Geography at the University of Kentucky, was motivated by a central contradiction: While queer women and trans people often long for a “gayborhood” to call their own, their lower incomes compared to their male and cisgender counterparts makes it difficult to acquire and keep real estate in expensive cities like New York. And it’s even more difficult for queer and trans people of color, who are more likely to live in poverty than white LGBTQ people. While lesbian bars have long provided spaces of community for queer women, they experience notoriously high turnover, often falling prey to rising real estate prices and gentrification. In the decade since Gieseking started his research, 37 percent of the country’s gay bars shut down, including 52 percent of lesbian bars and 59 percent of bars primarily serving queer people of color.

Because of this displacement, lesbian and queer people are often forced to create community in creative ways and unexpected places. “Largely lacking the financial or political capital to secure long-term spaces, lesbians’ and queers’ places are more scattered and visible only when you know where and when to look,” writes Gieseking. A Queer New York offers readers a glimpse of these unexpected places of queer community, from bars to grocery stores to corner pizza shops. The project also explores how New York City’s many ills, especially racism and gentrification, shape how queer people experience the city.

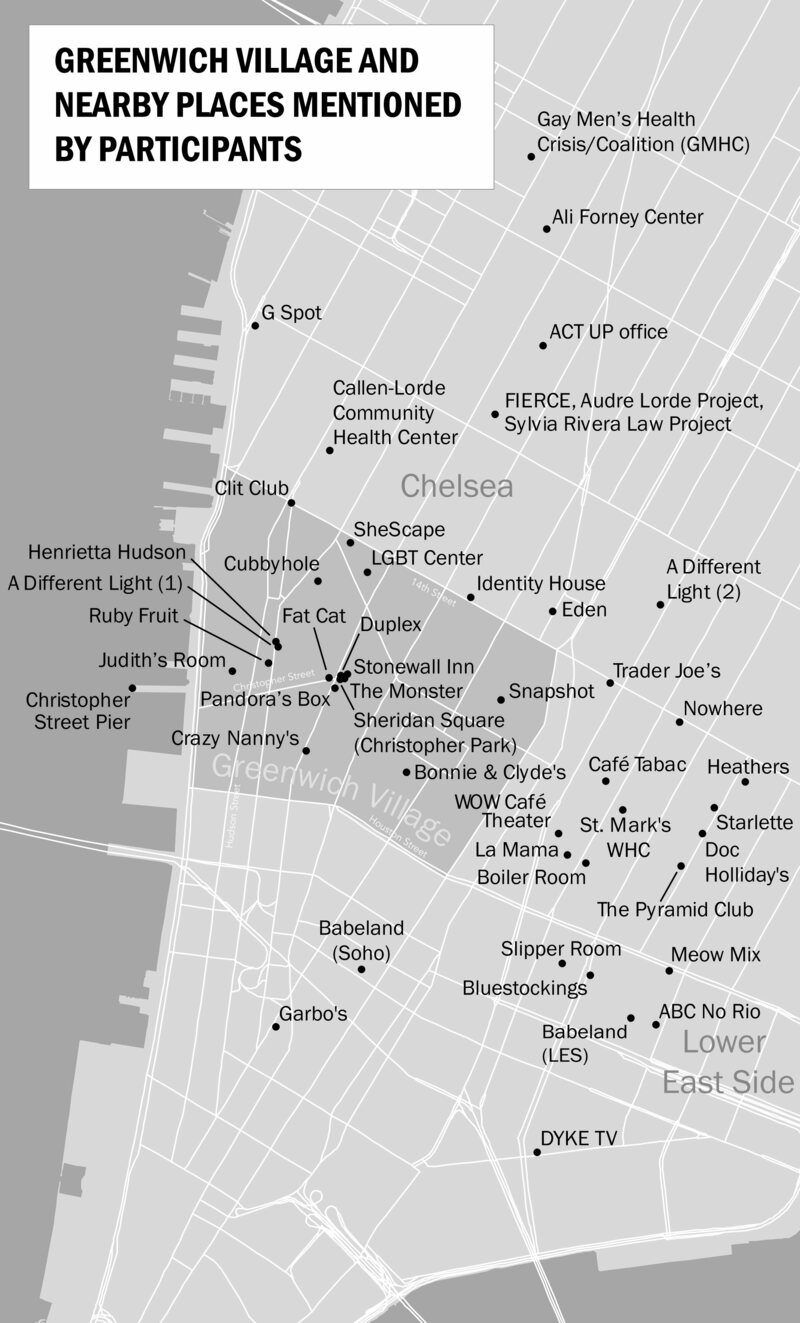

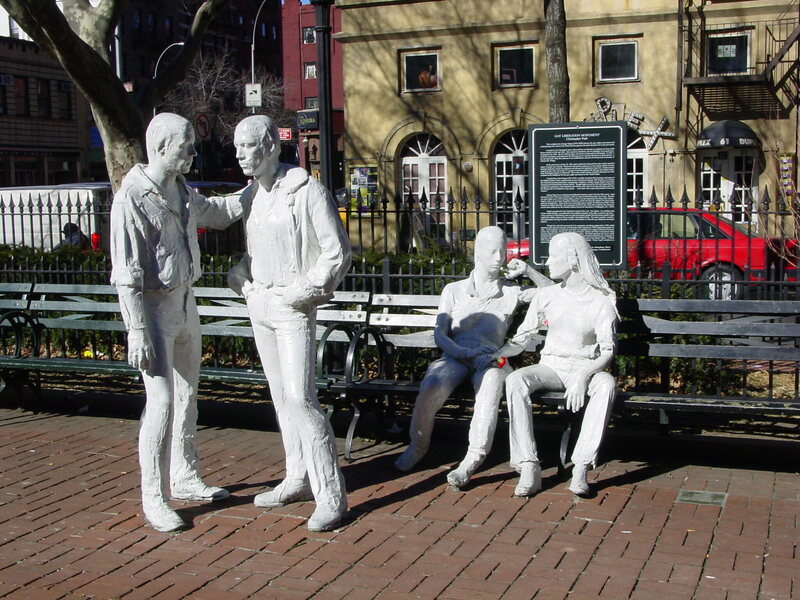

Gieseking’s focus groups included many laughter-filled conversations about the sexy goings-on at popular lesbian bars. Haunts like Crazy Nanny’s, Meow Mix, Pandora’s Box, and the Clit Club fill the interviews. “It’s an amazing space. It’s the place you go to dress up, to meet people,” says Gieseking of the lesbian bar. “To see yourself represented.” Yet as shown on Gieseking’s time-elapsed maps, these bars and parties are often ephemeral: Move the map’s slider across time, and they emerge and wilt like spring crocuses.

Other spaces that participants considered queer are more unexpected. The Park Slope Food Co-Op wasn’t the only grocery store: Trader Joe’s, too, was “one of the gayest places” in the city, according to a project participant. Meanwhile, queer people across generations—unbeknownst to each other—recalled drunken post-bar pitstops at Rivoli’s Pizza #2, a typical New York pizza joint in the Village. Gieseking realized that spaces like this, at first glance unremarkable, are actually pockets of pleasure and safety for people whose experiences of the city are plagued by harassment and precarity. They are “in the background of our lives and stories,” he says.

Yet for many participants of color, queer spaces often meant exclusion as well as liberation. They mentioned racist practices at lesbian bars—some nightlife spots in the Village were known to ask patrons of color for three IDs, while hardly carding white visitors—and microaggressions from white queer friends. While most of the women and trans people experienced harassment navigating the city streets, queer people of color were especially targeted. “We’d use someone’s whiteness to get a cab,” said Naomi, an African-American lesbian who came out in 1989.

Compare Gieseking’s map of queer spaces to his maps of rising real estate values and changing neighborhood racial composition over time, and you can see these forces of segregation undergirding queer people’s experiences of the city.

Almost everyone Gieseking interviewed talked with fondness of the bars and coffee shops of Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. Yet only one participant could afford to live there—and that’s because her apartment was rent controlled. Many other queers were priced out or died of AIDs, and real estate developers snatched their apartments. “There was a sense of watching a neighborhood die and be commodified at the same time,” says Gieseking. Similarly, white queer people were instrumental in the gentrification of Brooklyn’s Park Slope, previously a largely Latinx neighborhood. Gieseking says now the neighborhood is too expensive for most low- and middle-income LBTQ people.

In Brooklyn, white LGBTQ people were often the first to gentrify neighborhoods of color, displacing lower income residents—including queer and trans people of color. When a white participant in one of Gieseking’s group interviews referred to Outpost coffee shop in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a rapidly gentrifying, historically Black neighborhood, as a “little gay haven,” a Black participant, who grew up nearby, expressed skepticism. After all, Gieseking writes, the bar’s very name, Outpost, which the white participant defended as a play on “coming out,” evokes colonial imagery of queer white gentrifiers “settling” the “frontier” of Black neighborhoods. In contrast, queer and trans people of color—many of whom organized against gentrification—fondly recalled spaces of their own, including queer dinners in majority-immigrant Jackson Heights and lesbian-of-color majority parties at Greenwich Village’s Crazy Nanny’s.

Today, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the closure of lesbian bars across the United States, with only 14 left in the country, and three in New York City. The Toasted Walnut, Philly’s last remaining lesbian bar, closed just this month, despite a crowdfunding campaign meant to keep it open. Meanwhile, a continued recession, which has disproportionately affected LGBTQ people, underscores the constant housing precarity the characterizes queer life in the city.

The ongoing loss of queer bars and eateries, such as MeMe’s Diner in Brooklyn, is sad for Gieseking and many of those who socialized there. Yet Gieseking invites readers to reflect on both the bad and good of the gayborhood. “There’s a reckoning that needs to happen with how we got the neighborhood, but also what that neighborhood afforded so many people who weren’t able to live there,” says Gieseking. Ultimately, he says, A Queer New York invites us to examine the creative and resilient ways in which queer people have historically created community, in order to imagine more just and welcoming spaces going forward.