BLAST OF SILENCE: Born to Die

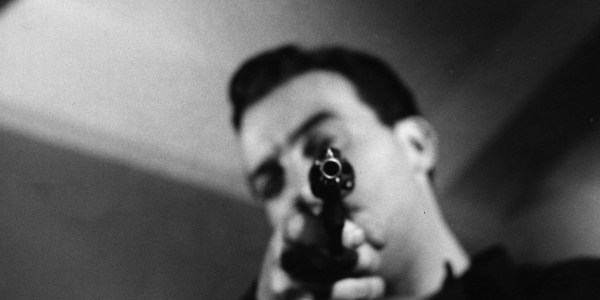

A pinprick of light perforates a pitch-black frame. A train rumbles. A woman screams. “Out of the black silence,” booms a guttural, menacing voice, “you were born in pain.” The light at the end of the tunnel grows larger. The woman’s screams die down, supplanted by those of her newborn baby boy. “You were born with hate and anger built-in,” the voice continues, “Took a slap on the backside to blast out the scream… and then you knew you were alive.” As the train emerges from the darkness into Manhattan, Frankie Bono (Allen Baron) enters the world, and for the next 70 minutes, we watch him hurtle down fatalistic tracks as he lusts, hates, kills, and dies, without ever really living at all.

As saturated with doom as the very best works of its genre, Allen Baron‘s Blast of Silence turns 60 this year—an anniversary that’ll be celebrated quietly by a handful of fans fortunate enough to have unearthed this bleak, brutal, underappreciated noir gem. That the film is largely unknown is a shame, of course, but undeniably quite appropriate, given its all-consuming preoccupation with separateness and self-imposed exile. Baron, both in front of and behind the camera, sustains an almost unbearably miserable descent through countless circles of chilly alienation, beginning with the cold womb of the tunnel, and ending with the even colder mud of a boggy grave, punctuated along the way by frustrated yearning and savage violence. Few films are as tangibly, desperately lonely as this.

Unhappy Holidays

Frankie Bono, the figure at the center of this yarn, is a hitman based out of Cleveland, whose work brings him back at Christmastime to his hometown, New York City, to kill Troiano (Peter H. Clune), a “second-string syndicate boss with too much ambition.” Hometown, though, doesn’t mean home, and the overwhelming feeling generated by Baron‘s writing and visual style are that Frankie would rather be anywhere else in the world than back where it all began for him, where something went terribly wrong in his life. With time to kill between tailing his target and waiting for his gun to be delivered, Frankie floats through the streets that shaped him, not with an air of nostalgic reminiscence, but of resentment. The memories that come flooding back to him are of innocence lost, Christmas wishes crushed and unfulfilled, emotional injuries inflicted by uncaring adults, and faces that he’d hoped to bury.

This is a dismal tale, dismally told by Baron and his collaborators, who sculpt an existential prison out of shadow and sound. Every filmmaking choice diminishes and isolates Frankie, emphasizes his powerlessness, and situates us deep within the dark heart of his consciousness, contributing to the prevailing sense of schism. Cinematographer Merrill Brody infuses the festive backdrop with bitter irony—the busy shop windows, the myriad lights, the joyful buzz of the city’s inhabitants, all serve to divorce Frankie even further from the rest of the world and drive him deeper into his own private sepulcher of psychological torment. Try as he might to blend in with the crowd, Frankie can’t help but seem more like an extraterrestrial visitor, observing the behavior of a strange species with barely-veiled hostility.

Hell Is Other People, and Yourself

So deep are Frankie’s wounds, so baked into his personality is his estrangement from all human connection, that even kindness, we sense, is an injustice to him. In one sequence, we watch as his solitary dinner plans are disrupted by an ambush—the unexpected arrival of an old acquaintance, whose voice we don’t even hear at first. Instead, we hear only the rasping commentary of the narrator, who excavates the magmatic irritation bubbling beneath Frankie’s fidgety crust, that suspicion that even in this restaurant, the universe is conspiring against him: “Why now? You feel hot like they were crowding in and pushing you. Who? Anyone. Everyone.”

That thoroughly distinctive second-person narration, omniscient and poetic, given grim portent by the gravelly tones of Lionel Stander, prods and chips away at Frankie’s psyche, plumbing his mind for past traumas and present anxieties with which to taunt him at every turn. It’s a uniquely unsettling conduit into Frankie’s tortured soul, providing painful insight after painful insight into the roots of his uprooting. It also crystallizes the worldview that motivates this merchant of death, the philosophy behind the gun. “The sisters at the orphanage used to say, ‘God moves in mysterious ways,’” Stander‘s narrator growls, as Frankie surreptitiously observes his prey, “Sometimes you wonder if he moved you in to rid the world of men like Troiano.”

The animating power of Frankie’s simmering rage is what sets Blast of Silence apart, psychologically, from the other existential hitman masterpieces of the era, to which Baron‘s film is broadly comparable: Irving Lerner‘s 1958 film Murder by Contract, and Jean-Pierre Melville‘s 1967 film Le Samouraï. Lerner‘s killer, the methodical and businesslike Claude (Vince Edwards), is driven by the promise of quick cash and a vision of the American dream, while Melville‘s killer, the monastic Jef Costello (Alain Delon), is a creature of principle and habit. Frankie’s approach to the profession is far more primal, tapping into bottomless reservoirs of fury—killing, for him, is an outlet, a relief valve for the hatred that he feels towards his father, the nuns at the orphanage, the architects of his anguish. Frankie’s modus operandi, seemingly patient and precise, disguises an emotional need—as Stander informs us, Frankie’s reconnaissance strategy has as much to do with learning to loathe his victims as it does with learning their patterns of activity.

Allen’s Artistry

On the surface, too, Frankie is distinct from his cinematic killer kin. Both Edwards and Delon exude coolness with every word and every action, swaggeringly detached in their self-presentation. Baron‘s performance, meanwhile, is unrefined, stilted, but certainly not ineffective—his gracelessness translates into plaintiveness, transmitting a persistent air of discomfort that marks Frankie as an eternal outcast. Yoked with unease by Baron, Frankie shifts, twitches, recoils, out of place not just when he’s in the presence of others, but even when he’s alone, an island of perpetual agony.

While it’s his unassuredness as an actor that makes him such a transfixing screen presence, there’s nothing unassured about Baron as a visual craftsman. Blast of Silence is the work of a neophyte director, but looking at some of Baron‘s conspicuous formal touches, his spatially sophisticated and thematically dense compositions, you’d think it’s the work of a consummate maestro. Two moments, in particular, stand out as emphatic visual flourishes—the first is a protracted wide shot at dawn, in which Frankie, in the style of Omar Sharif‘s spectacular introduction in David Lean‘s Lawrence of Arabia (although actually predating Lean‘s film by a year), starts as a speck of darkness on the distant horizon, and walks all the way into the camera lens, more alone than ever after viciously murdering a repulsive acquaintance. The second is an extreme low-angle shot that looks up from the street at Frankie, who looms, silhouetted, over Troiano from the roof of a building—it’s an image that should, you’d think, position Frankie as an elemental force of fate, in godlike command of his target’s life or death, but instead only seems to reinforce his smallness, his inability to alter his own existence and destination.

Conclusion: Always Alone

Baron would never really emerge as the formidable filmmaker that this auspicious debut, his first and only masterpiece, seemed to promise. The rest of his oeuvre is almost entirely tethered to the small screen, including credits on The Brady Bunch, The Dukes of Hazzard, and Charlie’s Angels. Only three further feature films appear in his body of work—Terror in the City, Outside In, and Foxfire Light—all of which are buried even deeper than Blast of Silence beneath the rubble of obscurity. It’s undoubtedly unfortunate that we only really have Blast of Silence as evidence of his skill because it’s seriously compelling evidence—fans of the film no doubt mourn the desolate neo-noirs that we never got.

Still, it’s hard not to recognize, once again, just how appropriate it is that this film, with its unforgiving vision of irreversible isolation, seems to exist in its own specific vacuum, suspended in a sort of solipsistic limbo. It’s a truly singular achievement, straddling the threshold between noir and neo-noir, never surfacing for long enough to gain any meaningful popularity, merely a peculiar artifact in the varied careers of its creators. Maybe that’s just how things were fated to be. Maybe Stander, narrating as Frankie steps off of the train and through the gates of hell, says it best: “You’re alone. But you don’t mind that. You’re a loner. That’s the way it should be. You’ve always been alone. By now it’s your trademark.”

What are your thoughts on Blast of Silence? What are your thoughts on neo-noir films? Let us know in the comments below.

Watch Blast of Silence

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!