Plummer Pulled Off the Impossible in ‘All the Money in the World’

The recent passing of the great Christopher Plummer brings to mind his incredible body of work, with his Oscar-nominated turn in “All the Money in the World” especially worth revisiting.

While the 2017 movie received ample pre-release publicity for its wild production history (namely, how a disgraced Kevin Spacey was replaced by Plummer just a month before release), few have seen the film itself.

It’s a shame, as Ridley Scott’s roaring, seductive “World” is among his finest works and Plummer’s performance is, likewise, one of his best.

It begins in Rome, 1973. A young, long-haired and utterly free “Paolo” J. Paul Getty III walking around the streets of Rome, a black and white vision that resembles the allure of Fellini. The establishing scenes draw us into this intoxicating world, though the state of bliss is fleeting.

Paolo is kidnapped and held for ransom, but the ua-rich J. Paul Getty Sr. (Christopher Plummer) refuses to buy his grandson’s freedom.

As the central plotline develops, we get flashbacks of Getty emerging from a train into the Saudi desert, playing like an outtake from a David Lean film. We see that Getty is clearly, “the richest man in the history of the world,” a title he carries in his every move.

A juicy line that Plummer nails- “if you can count your money, you’re not a billionaire.”

Related: Plummer’s ‘Man Who Invented Christmas’ Arrives at the Perfect TIme

The fractured narrative builds the details of Paul’s kidnapping (and J. Paul Getty’s reluctance to get involved) with the story of how the estranged Getty welcomed his black sheep son into his life and truly made Paolo and his siblings official family members.

This sequence, in which Gail Harris, a Getty by marriage (Michelle Williams), her husband and kids are living in a cramped apartment and are summoned to join royalty, is set to “Time of the Season” by the Zombies. It carries the spot-on lyrics: “What’s your name, who’s your Daddy, is he rich like me? Has he taken any time to show you what you need to live?”

Early on, we’re introduced to the totem of the minotaur, a vital clue, echoing the wooden horse of the Scott-produced “Blade Runner 2049,” released a mere two months apart. The minotaur, a key gift that J. Paul Getty gives Paul, is handed to him with the telling words, “everything has a price.”

The way screenwriter David Scarpa has Gail circle back to the minotaur much later on is a brilliant touch.

Paolo’s captivity and the unexpected ways his situation keeps changing are always compelling. While Scott has never again made a film as grisly as his “Hannibal” (2000), the portion here involving the removal of an ear, as restrained as it is, demonstrates (as did his woefully underrated 2013, “The Counselor”) how Scott’s ability to shock remains intact.

Scott resists making this an action movie, a decision that, unfortunately, keeps the suspenseful climax from being as satisfying as one would hope. Rather than a chase with a rousing finish, it’s more of a search with a sudden reconciliation. A stronger decision is, while the final moments of the messy kidnapping arrangement take place, Scott keeps cutting back to Plummer.

A bit of dramatic license is taken during the big climax, in which the last moments of Paolo’s ordeal are contrasted with J. Paul Getty’s own final moments. Scott makes the old man’s mortality slip away once his family is no longer in his control. Plummer’s closing scenes and his bravura performance aren’t the only operatic touch here.

Notice the use of a roaring fire during the business deals in Getty’s lair, an indication of a Dante-esque fate awaiting the man. Getty’s world is devoid of life, as the color palette is muted, whereas other scenes have a richer color scheme and beauty.

A perfect, wryly funny epilog, reveals how J. Paul Getty has become one of his own artworks — cold, marbled in stone, likely priceless and devoid of life.

The cinematography by Darius Wolski, score by Daniel Pemberton and editing by Claire Simpson are all Oscar-worthy, though its Plummer’s work that is the film’s greatest legacy. It’s among the best in his legendary career.

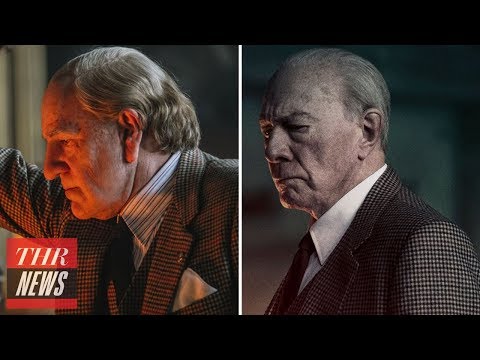

As the press reported tirelessly in the buildup to opening day: a scandal involving Spacey plagued the project, but Scott and his collaborators decided to save the film by removing Spacey altogether.

Enter Plummer, who took over the role of J. Paul Getty and, on Nov. 22, 2017, the cast returned to Rome and shot 22 scenes in 8 days. Scott and his crew pull off the rushed post-production and made the opening date. The edits are so seamless, with the new footage integrated so perfectly with the original cut, you’d never guess Plummer’s scenes were shot only a month before the film’s opening day.

Plummer’s scenes are the film’s best, ironic considering the unprecedented manner in which he joined the cast. There is a richness to his work here, an understanding of the mindset of someone so impossibly wealthy, it makes the psychology of his scenes understandable, even as the character is maddening.

Scott’s career-long exploration of the social divide and class differences remains timely, thoughtful and clever; notice how a scene of a business deal, involving the bargaining of a work of art, cuts to a sequence taking place in a deli.

Everything and everyone is getting bought and sold.

Take note of how the subject of class divide is in every one of his films: here’s but a few examples, from the blue collar astronauts in “Alien” (1979), the rulers and warriors of “Gladiator” (2000), “Kingdom of Heaven” (2005), “Robin Hood” (2010) and “Exodus: Gods and Kings” (2014), the peasants and monsters of “Legend” (1986) and the middle class cop protecting the wealthy social elite in “Someone to Watch Over Me” (1987) are all about characters divided by levels of class and social status.

“All the Money in the World” may be Scott’s final word on the subject and it leaves a real sting. The contrast of J. Paul Getty’s dilemma of having everything but nothing of emotional value versus Gail having no money but possessing the things in life that truly matter is a potent theme.

Williams’ icy, affecting turn is strong enough to elicit our compassion and her work here gets better with repeat viewings (her best choices as Gail are subtle and smart).

Mark Wahlberg’s sharp performance as J. Paul Getty’s right-hand man and Gail’s hostage negotiator makes up for how miscast he is. At times, he recites his lines too quickly. Wahlberg takes some time to grow into the part and his final scene with Plummer has real bite and is his finest in the film.

If you only know this as The One That Spacey Was Erased From, then that’s not enough. Scott’s triumph here isn’t just the crisp storytelling, his masterful ability at world building and creating imagery that immerses his audience, but an understanding of how money can control us and make everything in our lives an empty commodity. Notice how the kidnappers are, after all, only slightly more ruthless than J. Paul Getty.

As a cautionary tale of not succumbing to the distance money provides those hungry for power, it speaks to our need to look past one’s bank account and location, in order to see what it is that makes us truly human.

The post Plummer Pulled Off the Impossible in ‘All the Money in the World’ appeared first on Hollywood in Toto.