Inside the World’s Largest Jewish Cookbook Collection

Roberta Saltzman shopped a lot on eBay. Often, her purchases fit into one narrow category: Jewish cookbooks, the more obscure, the better. Never mind that Saltzman, who died in 2014, was by all accounts not that interested in cooking. Over the years, she accumulated 700 Jewish cookbooks, with a particular focus on community cookbooks from small-town America. Despite being chief assistant librarian at the New York Public Library’s Dorot Jewish Division, Saltzman used her own money to build her collection, which she donated to her workplace before her death. Now, at more than 2,500 books, the collection is likely the largest in existence, drawing researchers from around the world.

That number of books is something of a lowball estimate, says Dorot Jewish Division research librarian Amanda Siegel. She admits that she doesn’t know whether the collection is the world’s largest or not, since many other Judaica collections around the world also own flourishing cookbook collections. But the entire Dorot library, cookbooks and all, is one of the largest Judaica collections on the planet, at a quarter-million items.

While the Dorot Jewish Division continues to acquire new culinary material, the process is slower without Saltzman at the helm. “It’s really her collection,” says Seigel. While newly published Jewish cookbooks are constantly being added to the shelves, Saltzman’s interest in regional, often community-made cookbooks made her acquisitions unique. Choice examples include The Bah-Haimisha Cookbook, put out by a congregation in the Bahamas in 1960, as well as Blast Off With Blintzes from the Sequoia Chapter of Hadassah in Palo Alto, California. The collection’s range, though, stretches far beyond the Americas. “We have cookbooks from Switzerland, from Panama, from Venezuela, [and] from the Philippines,” Siegel rhapsodizes.

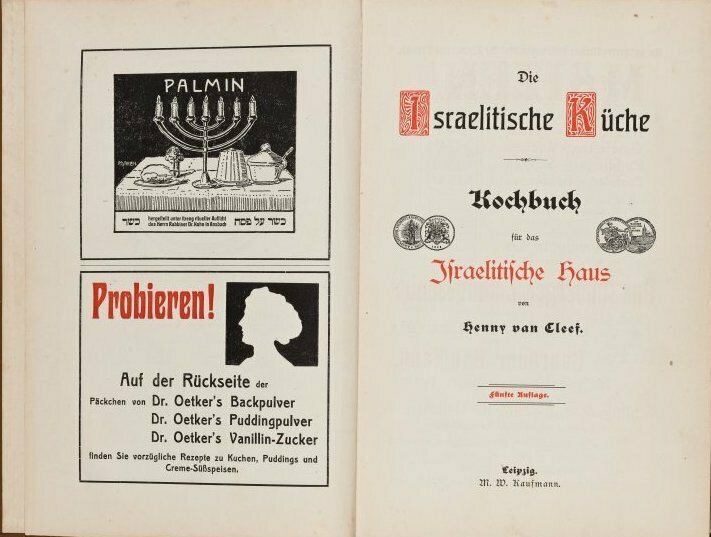

But the collection isn’t just humble, comb-spined community cookbooks. There are lavishly decorated tomes, such as Die Israelitische Küche, published in Germany around 1910, as well as flimsy marketing pamphlets with recipes sent out by big brands interested in catching the eye of mid-century Jewish housewives. One such booklet, by the Crisco shortening company, has recipes for Southern-fried chicken and macaroni salad, printed in both the Hebrew alphabet and English. Saltzman herself donated one eyebrow-raiser, 25 Unorthodox Things To Do With A Hebrew National Salami.

Despite their diversity, Seigel says that Jewish cookbooks are nevertheless a single genre due to religious observances and customs, especially cookbooks focused on holidays. “During most Jewish holidays—not all, but during most—there are categories of work that are religiously prohibited,” she says. “For example, lighting a fire. So a lot of these recipes were developed to cook very slowly and safely or to be kept warm over a flame.”

Siegel points out that, since consuming leavening agents and most flours is forbidden during Passover, the holiday merits special consideration in the collection and in many of the cookbooks themselves. One matzo torte recipe, in a 1902 community cookbook from Los Angeles, calls for matzo meal, ground almonds, chocolates, 10 egg yolks, and whites “beaten to snow.” In The Center Table, a Boston community cookbook from 1922, Passover merits its own chapter, filled with recipes for potato cake and “Matzoth Meal Pan Cakes.”

One of Siegel’s favorite books in the collection is actually a Passover cookbook. She hoots with laughter as she reads the title over the phone. “It’s called, The When You Live in Hawaii, You Get Very Creative During Passover Cookbook,” she says.

Cute titles aside, she notes, the Dorot Jewish Division’s cookbook collection is an important resource, one utilized constantly by scholars and writers. One researcher crossed the globe after learning that the NYPL owned the largest-known collection of South-African Jewish cookbooks, which Siegel estimates is still only around a dozen. A writer has researched the possibly Jewish roots of the meat dish ropa vieja, while a rabbi has used the books as a primary source for a book about chocolate.

Saltzman’s beloved community cookbooks, though, may be the collection’s most poignant historical records. “You find cookbooks from really small towns that might not even have a really active Jewish community anymore,” Siegel says. A humble cookbook, stained with fingerprints, ragged around the edges, and purchased off eBay for a song, can become “the only documentation of that community.”