‘Where Are My Children?’ and Lois Weber’s Trailblazing Films About Women

Beyond the Classics is a bi-weekly column in which Emily Kubincanek highlights lesser-known old movies and examines what makes them memorable. In this installment, she highlights the historical value of Lois Weber’s Where Are My Children?

Few filmmakers knew how to make silent films about women as well as Lois Weber. Social topics barred from most feature films were never off-limits for Weber, who came to fame thanks to her scandalous political films of the 1910s. Weber’s films were revolutionary for their time, and even now they depict historical events like the birth control movement and the complicated ideas that came with them in rare moving image form.

Thanks to Weber’s insistence on bringing tough realities into narrative film, we can see how women viewed the subject of birth control and abortion more than one hundred years ago in Where Are My Children? (1916). Weber fictionalizes Margaret Sanger‘s landmark obscenity case in an emotional story that is still fascinating to watch today. One of her first social issue films, Where Are My Children? kickstarted a career centered around crafting remarkable films about women’s issues, even if those issues are thought of differently today.

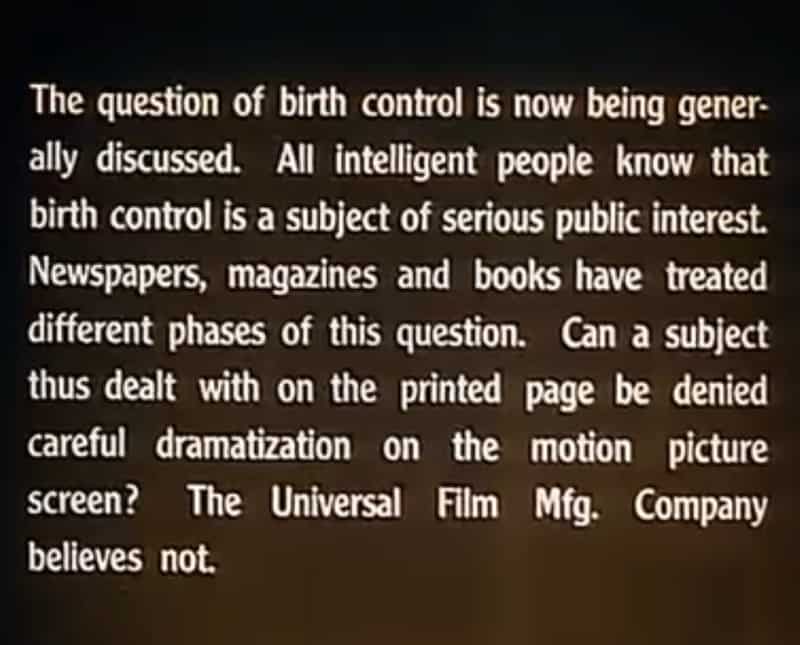

Co-written and co-directed by Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley, Where Are My Children? is not shy about its political stance on birth control. The film begins with a statement onscreen stating the importance of discussing birth control and Universal’s support of depicting the subject in a drama film. While the studio and filmmakers note the necessity of adults having access to this film, it does not condone unsupervised children being subjected to the topic of birth control. The choice to begin the movie with a stark declaration of intent gives viewers a clear indication of what they’re in for, which was something audiences in 1916 had yet to experience.

The film then enters Heaven’s gates, where a golden hue tints the angelic images of clouds and angels. The intertitle cards tell us that unborn children reside here until they are either born on Earth, often unwanted, or they’re sent back to Heaven, hinting at abortions. Immediately, this is much different than most movies we watch today that deal with abortion or birth control, but the religious perspective on reproduction was the perspective many people understood in 1916. Weber knew this and recognized the effect it would have on capturing its audience. To modern viewers watching today, it’s the first of several signs of this film’s age, but also of the historical value of the film, too.

The main plot of Where Are My Children? centers around District Attorney Richard Walton, played by Tyrone Power, Sr., and his wife, Mrs. Walton. They live a lavish life but lack the one thing Mr. Walton longs for: a family. His wife cannot have children and so he soaks up time with his nieces and nephews to fill the void. Mrs. Walton is a socialite and liaison between her high-class friends who need abortions and the one doctor she knows will perform them in secret. What she isn’t telling her husband is that she is capable of having children but isn’t ready to be a mother yet and has had several abortions herself.

One of the events that impact the Waltons is a case that Mr. Walton takes on involving a Dr. Malfit, who has been charged with obscenity for distributing pamphlets on the new idea of birth control. This is a direct reference to Margaret Sanger, who coined the term birth control and was charged with obscenity two years earlier in 1914. Sanger, like Dr. Malfit in the film, spent time as a nurse in the poorer neighborhoods of the Lower East Side of New York City. There, she witnessed similar scenes depicted in the film, including worn-down mothers with more children than they can feed. The overcrowding and lack of sexual education in poorer neighborhoods led Sanger to advocate for efforts of preventing pregnancy before the need for abortion.

Many adults did not understand how to prevent pregnancy on their own, since the topic of sex was far too foul a topic to discuss openly. This is what led Sanger to distribute several magazines and pamphlets on the subject, including one in 1914 titled Family Limitation. This is also what led to her being indicted for obscenity. However, she did not plead her case in court like Dr. Malfit does in the movie. Instead, she fled to England, where she hid out and educated herself on European birth control methods until the charges against her were dropped.

The Dr. Malfit case takes up a small portion of Where Are My Children?, but its role in the film and in representing the birth control movement as a whole is very important. Sanger is a figure with a complicated legacy as we look back at what she believed in during the years she advocated for birth control and eventually founded the first Planned Parenthood. She, like many scientists and doctors at the time, supported the concept of eugenics as a viable reason for birth control within the United States.

Eugenics is most notably connected with the torture and genocide perpetrated by Nazis during World War II, but before that, many prominent Americans advocated for some kind of “selective breeding.” Even before the Nazis, eugenics was grounded in prejudice and racist ideals that viewed poor families, disabled adults, or people of color as lesser choices for parents. Since the invention of birth control by Sanger and the Nazi’s eugenics “experiments,” the beliefs that backed eugenics have been discredited. However, it’s important to consider when we remember the birth control movement and first-wave feminism of the early 20th century.

Eugenics bleeds into Dr. Malfit’s case in Where Are My Children?, especially in the dramatized scenes of the doctor working with poorer families before his arrest. The people he takes care of are either helpless or drunks who are deemed unfit for parenthood. Many believe today that this sentiment underlined a lot of how advocates for birth control thought of people in poverty at this time. Eugenics is also within the other plots in the film that depict abortion.

Mrs. Walton helps her wealthy friends get abortions when they need them, but she also helps a young girl who is staying with the Waltons. They take in the daughter of one of their servants, but she soon comes under than charms of Mrs. Walton’s skeevy younger brother. She becomes pregnant, but the father wants nothing to do with her or her baby. Mrs. Walton takes the girl to her doctor, but the procedure goes much differently for this young girl. She stumbles back to their house after the procedure and collapses in Mr. Walton’s arms shortly before dying of complications from her abortion. Like the rest of the lower class characters, the young girl does not sidestep the consequences of unprotected sex and perishes as punishment.

Soon after, Mr. Walton takes the doctor to court for performing illegal abortions, and he learns that his wife has been lying to him and using the doctor’s services as well. When Mr. Walton finds his wife and her socialite friends having a party at his home when he returns, he goes on a rampage. He tells them that they are selfish heathens who are killing what should be children born to further the human race. These women are viewed as potentially the only thing worse than a poor mother of many children: a childless wealthy woman.

The outdated morality within the plot of Where Are My Children? is vastly different than what is believed today in terms of a woman’s right to abortions and why birth control is important. Still, it is a historical feat for Weber to have put these controversial and complicated topics on screen. When most movies skirted around the social issues involving American women, Weber put them front and center. It’s thanks to her insistence on incorporating everyday issues into her films that we can see the origins of birth control, as problematic as they may be.

We also see in the story the prevalence of abortions at the time, which has been distorted when people discuss the history of abortion today. Weber’s film is an artifact that we can analyze alongside Sanger’s speeches or pamphlets as representations of this point in history. It also laid the groundwork for films that we watch today about abortion in our current political climate, like the fantastic 2020 drama Never Rarely Sometimes Always.

Where Are My Children? also led Weber to a prolific career in representing women in feature films. While it sparked massive controversy throughout the country, leading to bans on screening the film, it also led to significant recognition of Weber’s name as a filmmaker. She soon became the highest-paid director, male or female, of 1916, and went on to make more films focused around women’s issues, including her masterpiece Shoes that same year. Eventually, Weber’s contributions and control over her films outshined her husband’s, and she made films on her own, even creating her own production company. Other films she made that were concerned with women’s experiences include What Do Men Want?, The Blot, and Too Many Wives.

Social issue films started to become outdated in the latter half of the 1920s, but Weber’s legacy has gained recognition in the past few decades. Beyond her ability to bring reality to movies, she has created some of the most striking images in cinema history. The cracked mirror shot in Shoes is an iconic image in and outside the world of film. And Where Are My Children? ends with Mr. Walton and Mrs. Walton sitting by the fire with their ghostly children they never raised hovering behind them, which is a scene as haunting as they come.

Lois Weber remains one of the greatest filmmakers of the silent era and her films are a rich source for understanding the social consciousness of the early 20th century. She dared to create social change via entertainment, which reached more people than other activists realized. Addressing the audiences’ lived experiences also moved them in ways other films that tried to separate themselves from real-life could not. Weber was committed to making the films she wanted to make, which were inseparable from politics. To Weber, “Truth holds her mirror up to politics.”