Jessica Walter: 1941-2021

That wink. Over six decades in film and television, from her breakout film work playing characters as varied as obsessed stalkers and sharp coeds, to her TV ubiquity on various hour-long procedurals about lawyers and the FBI, to her memeification as two of TV’s most formidable mothers, that wink told you Jessica Walter was willing to go wherever the character would take her. As a vivacious, unhappy wife in John Frankenheimer’s “Grand Prix,” and an increasingly cynical, unapologetically ambitious college graduate in Sidney Lumet’s “The Group,” and the woman scaring the hell out of Clint Eastwood in his macho-man heyday in “Play Misty for Me.” As a guest star on a slew of some of the biggest TV series of their day: “Mission: Impossible,” “Barnaby Jones,” “Columbo,” “Hawaii Five-O,” a crossover episode of “Magnum, P.I.” and “Murder, She Wrote.” And of course, as the high-key racist, blissfully uninterested in her children, wonderfully petty Lucille Bluth on “Arrested Development,” and the fantastically droll, endlessly judgmental, ferociously protective Malory Archer on the animated FX series “Archer.” If there was a joke, Walter was always in on it, and she was probably the one delivering it in that honey-over-gravel voice. She died in her sleep on March 24, 2021, and was 80 years old.

In a statement confirming Walter’s death, her daughter Brooke praised “her wit, class and overall joie de vivre,” and the news sparked an avalanche of condolences and memories from her costars and colleagues. Many of them came via Twitter: “Arrested Development” executive producer and narrator Ron Howard thanked Walter for a “lifetime of laughs”; “Archer” costar Aisha Tyler described her as “the brilliant center of our [“Archer”] universe”; onetime costar Dylan Gelula shared “Once she turned to me and said ‘Don’t let them f— with you’.” That advice takes on a certain resonance when you remember the way Walter stood up for herself against “Arrested Development” costar Jeffrey Tambor and publicly called out his verbal abuse in a 2018 New York Times interview.

Listening to the audio of that interview is painful: Walter is clearly in tears, Jason Bateman is talking over her (he would later apologize for “mansplaining”), and the only person standing up for her is Alia Shawkat. But Walter never wavers from the truth of her experiences, and demonstrates exceptional grace in stating her desire to forgive Tambor despite his mistreatment. That was the kind of woman Walter seemed to be: iron-willed but generous, self-assured but approachable. In the 2019 Elle magazine Legends issue, Walter said of her career, “I thought, ‘Wow, I guess I am a character actor.’ Because even my ‘leading ladies’—you know, in air quotes—were characters,” she says. “They were not Miss Vanilla ice cream. They weren’t holding the horse while John Wayne galloped into the sunset.” She was right.

Walter grew up in Astoria, Queens, her father a world-class musician and member of the NBC Symphony Orchestra and the NYC Ballet Orchestra and her mother an immigrant from the USSR. After attending the Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theater, she had a breakout year in 1966, working with two of America’s most prestigious directors at the time: with Lumet (“12 Angry Men,” and later “Serpico,” “Dog Day Afternoon,” and “Network”) on “The Group” and with Frankenheimer (“Birdman of Alcatraz” and “The Manchurian Candidate”) on “Grand Prix.” The films couldn’t be more different. “The Group,” based on a novel by Mary McCarthy, was about a group of female friends who met while attending what is clearly a Vassar College stand-in, and followed the graduates as they navigated their personal and professional lives in the 1930s. “Grand Prix” focused on four Formula One drivers competing in the 1966 season, and juxtaposed their races with their contrasting backstories, motivations, and romantic lives. And yet Walter received notice for her strong work in both, and for what was already a duality of warmth and bitterness. A Baltimore Sun profile in 1966 described Walter thusly: “She has what a beauty editor would call a model face, all bones, marvelous eyes and sculptured mouth,” and the piece concluded with, “The question is asked as to which of the [eight actresses in ‘The Group’] will make the biggest impression. One would certainly put a confident bet on Jessica Walter. As they say in the theater, she comes on strong.”

That kicker turned out to be prescient: Walter and Lumet would remain friends and work together again on the 1968 comedy “Bye Bye Braverman.” And when Eastwood was looking for an actress to play the dejected, obsessive Evelyn Draper in his directorial debut “Play Misty for Me,” Walter’s work in “The Group” remained on his mind. The two met, and as Walter told Elle, “I never read, I never had an audition” before being cast by Eastwood. Her Golden Globe-nominated work in “Play Misty for Me” is agonizingly sympathetic and deeply terrifying, primarily thanks to Walter’s elastic face. She excels at oppositions: the transition from a flirty grin to a self-effacing “Have I done something wrong?”, and then from tear-filled begging to her wide-eyed shriek, “You’re not even good in bed!” The scene where she emerges screaming from a pitch-black doorway to thrust a gigantic pair of scissors into a snooping detective’s chest is phenomenal, and the mannered-cum-feral quality Walter brought to Evelyn makes the film. In his review, Roger Ebert wrote of her “unnerving effectiveness”: “She is something like flypaper; the more you struggle against her personality, the more tightly you’re held.” The rejected woman has had a long life in pop culture, from Stephen King novels to Michael Douglas’s entire 1980s to 1990s career, but Walter’s particular shadow loomed large.

After “Play Misty for Me,” Walter jumped back to TV, working steadily as a guest star on series like “Columbo” and “Hawaii Five-O” before landing a series of her own, “Amy Prentiss.” The “Ironside” spinoff would only last for three two-hour episodes; as a rule, Walter didn’t have the best luck with spinoff series. “Three’s a Crowd,” the “Three’s Company” offshoot in which she had a recurring role, was also canceled after only one season. But Walter won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or a Movie for her “Amy Prentiss” work, and a photo from the May 19, 1975 ceremony, with Walter looking like a dish in a white halter gown and being kissed on the cheek by fellow Emmy winner Peter Falk of “Columbo,” is a clue as to how beloved by her costars Walter was. She appeared on four different episodes of “Murder, She Wrote,” throughout the 1980s and 1990s. She acted alongside real-life husband and fellow actor Ron Leibman on the 1995 “Law and Order” episode “House Counsel.” She worked with George Segal, who also came up in the 1960s and 1970s, on two sitcoms, “Just Shoot Me!” and “Retired at 35”; eerily, they would pass away within 24 hours of each other. She put a straight face on too-much-wokeness in the college comedy “PCU,” and her scene with a bemused Natasha Lyonne in the cult classic “Slums of Beverly Hills,” where Walter’s Doris tries to figure out a thong, is one of the movie’s most committed. She voiced the practical and loving allosaurus matriarch Fran on Jim Henson’s “Dinosaurs” series, and forayed into sci-fi on “Babylon 5,” and got a little meta by playing a former actress on the rebooted version of “90210.” Look upon her filmography and rarely a year goes by when she wasn’t working.

But when it comes to legacy, Walter secured hers by bringing to life two mothers who were quite awful and quite delightful in equal measure, whose snappiness and negligence were rivaled by their protectiveness and possessiveness. As the super spy-turned-demanding mother Malory Archer, Walter was coy and commanding, sly and beleaguered. Her loss is a tremendous one for “Archer” to surpass. The ensemble voice cast was full of zanier characters—H. Jon Benjamin as her narcissistic, womanizing, strangely-competent-when-he-tries son Sterling; Judy Greer, with whom Walter also worked on “Arrested Development,” as insane, glue-sniffing heiress Cheryl Tunt; Lucky Yates as the clone-and-anime-obsessed scientist Dr. Krieger—but Walter’s Malory was always the steadying force, the straight woman with a flask in her hand, irritatedly tut-tutting at her team’s antics. The role was a showcase for her beautifully mellifluous voice, which could be as sharply cutting as those knives Evelyn wielded in “Play Misty for Me” or girlishly flirtatious, as when Leibman joined the cast to play Malory’s husband Ron Cadillac. (As is Malory Archer’s style, though, the coquettishness with which she once treated Ron slowly gives way to a curdled tolerance.)

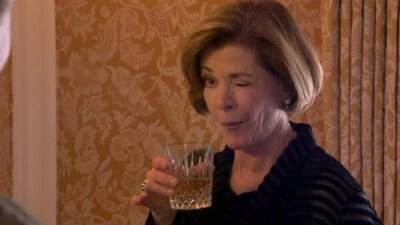

But the showcase for all of Walter was her work as Lucille Bluth on the infamously under-watched “Arrested Development,” which aired for three seasons on Fox before being revived by Netflix a decade later. Against a murderer’s row of comedians, including the aforementioned Tambor and Bateman, as well as Tony Hale, Henry Winkler, and David Cross, it’s Walter’s Lucille 1 who is always drawing your eye with her unwaveringly physical performance. Her glares, her squints, her eyerolls. Her frown—always, always a frown—when she’s assessing her children, or her puckered mouth when she lands a particularly good insult on them. The effortless fluidity of her mocking chicken dance, the cockiness of her catwalk at the Motherboy pageant, the cruel genius of her hiring away frenemy Lucille Austero’s (Liza Minnelli) apartment renovation crew to expand her own home into Lucille 2’s. It’s no mistake that every iconic, much-quoted line from “Arrested Development” is one of Walter’s, delivered in that voice that suggests indulgence as much as ignorance: “I don’t understand the question, and I won’t respond to it,” and in a later spin on that same sentiment, “If that’s a veiled criticism about me, I won’t hear it and I won’t respond to it”; “It’s one banana, Michael, what could it cost, $10?”; “I’ll drink you for it,” complete with her dismissive “That one didn’t count” after slamming back a shot; and, of course, “Here’s some money. Go see a ‘Star War.’”

It’s impossible to spend any time on Twitter without seeing a Lucille meme or gif, most pervasive of which is the one of her slowly shutting the door in her son Gob’s (Will Arnett) face after he suggests they spend time together. The door-closing scene is only five seconds long, but made perfect by Walter’s face: By her rapid up-and-down assessment of Arnett, by the narrowing of her eyes, by her left eyebrow quivering into a slash of suspicion. Walter’s Lucille injected absurdity into our traditional expectations of motherhood, and her version of maternal love was perhaps recognizable to so many of us because of its flaws: her criticism, her dismissiveness, her hovering. We loved Lucille and hated Lucille in equal measure, and it takes a real master to accomplish that. Jessica Walter was such an actor. May she rest in peace.