STALKER: From USSR With…

The empty and uninhabitable land that holds many secrets. The place where time, space and logic doesn’t work the way we all used to, the room that grants any wish to anyone who enters it obviously attracts a lot of broken souls that search for the last solution, curious people and gentlemen of fortune who want to profit from the land’s artifacts. The land created after the mysterious space object crashed on earth. People started calling this place The Zone, and unauthorized guides into it stalkers.

Production

But before we start analyzing the film itself, it’s only right to discuss the director and shooting of it as they are just as interesting as Stalker. Andrei Tarkovsky is definitely one of the critical filmmakers in history and the most famous one that was born in Russia. His father was a poet, and Andrei in a way was a poet, too, for his works can be perfectly described as poetic cinema. Although Tarkovsky himself hated the term “a poet” the themes of his movies, slow camera movements and extremely long one takes, the way his characters speak, and the words that come out of their mouths are nothing short of multilayered and yet humane poems. Production of nearly every of his movie was difficult at some point, from the spaceship in Solaris to the scene of a burning house in The Sacrifice that they had to build and burn down twice.

But the production of Stalker was worse than all of them combined, and even worse than the infamous production of Coppola‘s Apocalypse Now, at least because eventually, it led to the death of Andrei Tarkovsky.

First of all, the shooting near and inside the nuclear plant in Tallinn, Estonia, using rusted tanks and some other things that required a formidable budget. The first serious problem occurred after months and months of shooting they finally developed Kodak 5247 stock with which Soviet laboratories were not familiar with and what they got was dark and greenish, the film was ruined.

After seeing poorly developed material, Tarkovsky fired his first cinematographer, Georgy Rerberg. By that time he shot all the outdoor scenes and had to abandon them and even was thinking of dropping the project at all. And Mosfilm was thinking about it as well but they came up with the idea of making a two-part movie. They agreed to give him to try again and guess what? He hated his new DP so they had to find a new one and start all over again for the third time. It was Alexander Knyazhinsky, and by that time Stalker had changed in Tarkovsky’s head, and what we are able to watch now is completely different from what he had in mind during the first try.

But it wasn’t the worst that happened during the production. The shooting took place near several nuclear plants near Tallinn. Several people involved in the shooting including Anatoliy Solonytsin, Tarkovsky‘s wife, and Tarkovsky himself, died due to the film’s long shooting schedule in toxic locations.

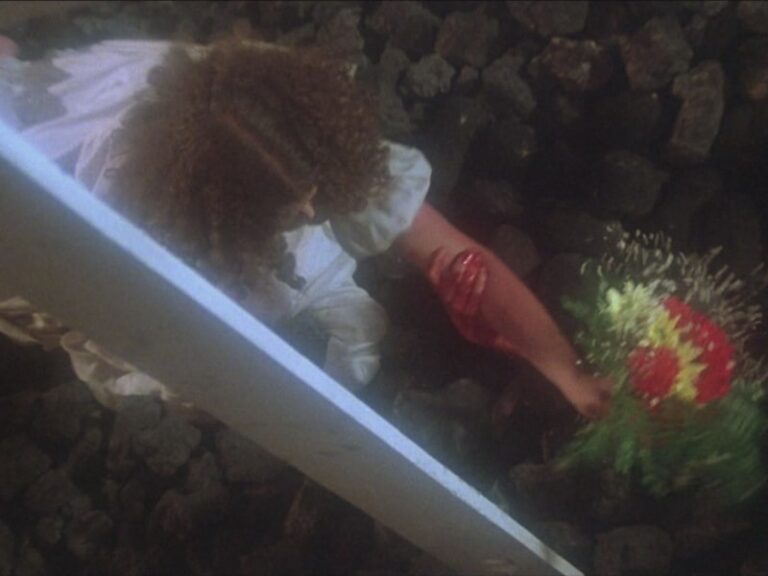

The Zone

Now, we can finally move on to the depiction of Stalker itself as one of the most ambitious and ambiguous works of art in history. The first thing a lot of viewers remember is the dialogue, and the dialogue is beyond words magnificent: witty, philosophical, and ambivalent. The lucid verbal disputes between the trio of The Professor, The Writer, and The Stalker with their unique and polar views on life, religion, and The Zone.

The Professor hides his intentions of why exactly he’s going into The Zone, he seems like the most reasonable of the three of our characters: The Writer goes into it to ask for inspiration but contradicts himself when he says that’s the inspiration that you simply buy doesn’t matter for a man writes or creates, in general, to prove something for himself and for the world, and this kind of inspiration wouldn’t matter to him for it’s fake.

While for Stalker the Zone is sacred land that should be treated appropriately; he’s genuinely scared when his wards disobey the rules of the Zone because he thinks that it may not like it and punish them like the others. All he wants is to make people happy with their granted wishes; he himself cannot be happy because he dedicated his life to try to make others happy; Stalker is a martyr of sorts.

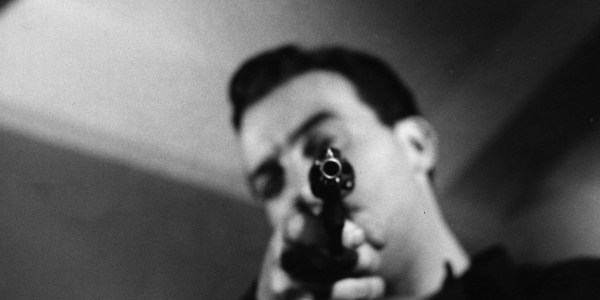

Naturally, there are many wondrous things in Stalker besides the dialogue – among them are signature for Andrei Tarkovsky moments of peacefulness and silence accompanied by an exceptionally magical and yet haunting score by Eduard Artemyev. Visually the movie offers you intimidating landscapes, exceptional framing of each shot and it seems like Tarkovsky found a way of photographing the human head in motion and repose that no one had been photographing before. Expressive but usually emotionally passive and silent faces of The Three glues the viewer to the screen as well as the scenery of The Zone.

The Zone itself is a whole another infrastructure with its own laws that don’t work in the outer world. It changes every time someone enters it: spawns anomalies in new places, creates physically impossible physical loops in a manner of Penrose stairs, and so on. The Zone knows everything about you; your deepest fears, anxieties, and desires.

Conclusion

Rewatching Stalker is always a joy although Tarkovsky‘s works are made not for entertaining but absorbing you. The thing is if a certain piece of art can absorb you for two or more hours, make you forget about the outside world, and make you question your own life, things you do and do not every day is a sign of a masterwork and as we all know Andrei Tarkovsky was exactly that guy to make us question things most people never even think about.

If I had one word to describe Tarkovsky‘s movies and especially Stalker I would choose “toska”; a Russian word that has no equivalents in English. Toska is the deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases, it may be the desire for somebody of something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level, it grades into ennui, boredom according to Russian writer Vladimir Nabokov. And Stalker is a movie equivalent of this word for me, it’s Russian doomer music in 24 frames per second.

After watching Stalker or other Tarkovsky’s works I always need a couple of hours just to rest, to think, to digest everything I’ve heard and seen in the past two hours. This movie remains one of the best existential crisis movies or at least can give you one.

Stalker is a road movie where characters go deeper into their own minds and what worries the deepest hidden corners of their body and soul. The movie is for sure will leave you mentally exhausted, and knowing the story of production and what happened afterward definitely doesn’t help it either.

What do you think about Stalker and did this overview of the movie make you want to watch it if you haven’t already? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!