How Scorsese’s ‘Cape Fear’ Did More Than Trump the Original

Martin Scorsese’s “Cape Fear” is a remake of a good movie, the 1962 Robert Mitchum/Gregory Peck thriller of the same name, and it’s better than the original.

The 1991 film begins with a roaring Bernard Herrmann score (faithfully recreated by Elmer Bernstein), an opening title credits sequence by Saul and Elaine Bass and shimmery imagery that isn’t entirely clear but very creepy.

Scorsese’s film, which followed his “Goodfellas” and was the first major hit for the great American filmmaker, is a visual feast from the very start.

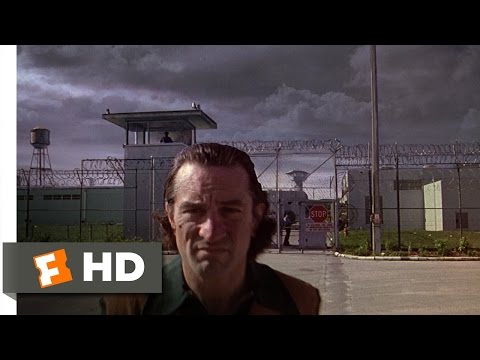

We meet Max Cady (Robert De Niro, pure muscle and intimidation), a convict being freed from prison after serving 14 years. As Cady departs the massive correctional facility looming behind him, lightning strikes in the distance and De Niro walks directly into the camera.

It’s not operatic, necessarily, but it certainly is pure cinema.

Cady immediately intrudes upon the life of Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte), his former public defender whose failure to save his client from a lengthy sentence goes beyond simply losing his case: Bowden quickly recalls how he buried evidence that could have altered the outcome of Cady’s sentence.

Cady, of course, knows this as well, since prison time has made him a self-taught authority on criminal law. Suddenly, Bowden’s comfortable existence (at least on the outside) is rattled by Cady’s interest in his wife, Leigh (Jessica Lange) and his daughter, Danielle (Juliette Lewis).

Cady’s intentions with Bowden are clear from the start, as he tells him, “You’re gonna learn about loss.”

This was famously a Steven Spielberg project that he handed over to the better-suited Scorsese, while the director of “Raging Bull” gave Spielberg the “Schindler’s List” project instead.

Talk about one of the all-time best cinematic tradeoffs.

Thelma Schoonmaker’s extraordinary editing is full of blunt transitions and smash cuts. There’s a propulsive rhythm to this, in which the first act coherently but briskly sets up the narrative, the second act finds telling moments for the pace to linger and the third act contains complex, elaborately produced imagery to convey the sense of a moral universe circling out of control.

Another filmmaking master, cinematographer Freddie Francis, makes this a tour de force in composition, use of color and how he uses the frame to keep us off balance. A number of moments (particularly the opening and closing introduction of Lewis’ character) overexpose the imagery into black and white, resembling an x-ray.

Scorsese’ re-use of Hermann’s score from the ’62 film oddly doesn’t clash with the modern-day setting- for that matter, the update works completely.

The whole thing is so flamboyantly stylish, it’s like Scorsese got jealous of Brian De Palma having too much fun over the years. Francis Ford Coppola, another towering filmmaker who, like Scorsese and De Palma, made his mark in the 1970s, would make his own grandiose, oversized genre film a year later: “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992).

There are numerous Hitchcock references in the cinematography, as well as visual nods to key moments from the original film. “The Departed” (2006) may have been the film that (far too belatedly) won the director his Best Director and Best Picture Oscar, but it was still a step down from the film it was based on, Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s “Infernal Affairs” (2002).

Here, Scorsese demonstrates that he understands the strength and appeal of the first “Cape Fear” but makes his version far darker, more explicit, thematically richer and cinematically frisky.

Early on, we have a scene that is framed in a way to make us feel like we’re in a movie theater and, for cinephiles and likely Scorsese himself, it is a vision of hell: the camera engulfs a movie theater screen showing “Problem Child” (1990), with John Ritter’s hamming it up interrupted by Cady walking past the screen and sitting in front of our vantage point.

Then, Scorsese drops the first-person view and shows us that Cady is obstructing the Bowden’s view of “Problem Child” (not a bad thing, really). Cady lights up a smelly, smoky cigar, puts his hands behind his head and laughs hysterically at the awful movie.

Cady is clearly doing it to annoy the Bowdens but Scorsese is, of course, commenting on the kind of idiot moviegoer who ruins the movie theater experience and, even worse, would find hilarity in something as awful as “Problem Child” (note how in the following scene the Bowdens talk about the obnoxious theater patron but never bring up the movie).

RELATED: Yes, Scorsese’s ‘Casino’ Out Hustles ‘Goodfellas’

The sequence that everyone remembers is when Danielle goes to her high school theater, thinking she’s meeting her new drama teacher for the first time, but is instead met by Cady, who verbally seduces her. Considering how brisk and aggressive the editing has been up to this point, it is both a wise and completely sadistic decision to have this scene be long, agonizingly slow and accompanied by no music.

Cady’s preying on Danielle’s curiosity and trust is tough to watch, which is kind of ironic, since it’s the film’s quietest and most subtle chapter.

De Niro and Lewis are doing master class acting in this, the most terrifying part of “Cape Fear” and one of its creative high points. What Spielberg reportedly envisioned in his unmade version as a chase sequence between Cady and Dannielle, Scorsese makes it about corruption of the soul.

With all due respect to Mr. Spielberg, I’m glad he stuck to “Hook” and passed on this.

FAST FACT: Both of Martin Scorsese’s parents were part-time actors, which likely gave the youngster an early appreciation for the craft.

Scorsese (unlike Spielberg) has never shied away from the darkness that people are capable of and how evil isn’t just a character quality but a poison that infects the soul.

“Cape Fear” is a harrowing work, surprisingly gory and overwhelmingly intense, with Scorsese’s flamboyant, playful direction matching De Niro’s ferocious performance.

With his constant cigar chewing, loud aloha shirts, thick as wahm buh-der accent and aggressive body language, De Niro doesn’t take the opportunity to grandstand as much as create a character who succeeds at making everyone around him believe he is always in control. Cady, like De Niro, is an actor with a gift at manipulating emotions — the character is a commentary on the power actors have over their “victims” (i.e., us).

Unlike his co-star, Nolte adapts a light accent and plays this completely straight forward. While Scorsese reportedly wanted Harrison Ford to play the role (which would have been a dream pairing), this is among Nolte’s best performances.

Playing Leigh, Lange characterizes her as a woman who can barely contain the rage underneath towards her husband; whether recounting the final moments of her dying dog or the awful pleading she makes during the climax, Lange is heartbreaking in this.

Lewis, who was 15 years old when the film was released, is utterly authentic, unforced and touching as “Danny.” The character is sharp and resourceful but has a weakness for attention and the excitement of the forbidden (like any teen, really).

Danny is into Jimi Hendrix, James Dean, dramas like “Look Homeward, Angel” and, as a trap Cady plants, the scandalous fiction of Henry Miller.

FAST FACT: “Cape Fear” earned $79 million at the U.S. box office in 1991. The year’s biggest film? “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” with $201 million.

Illeana Douglas, in the film’s other major breakout role, is terrific as Lori, a sort of “other woman” who refuses to be defined by either that term or, later on, as a victim. Douglas has been a force of nature in so many supporting roles, it’s a wonder that she has rarely been given a lead.

The casting of veteran B-movie actor Joe Don Baker seems out of left field at first, until you see how excellent he is here. As Bowden’s seen-it-all detective, he’s never been better.

Fred Dalton Thompson, the 90s character actor MVP who later entered politics, is typically solid here. He utters a key line, in regard to Bowden’s long-ago betrayal of Cady, with cruel irony: “Some folks just don’t have the right to the best defense.”

There’s also the clever scheme in the casting of Peck, Mitchum and Martin Balsam, the leads of the first “Cape Fear,” in cameo turns that reverse the nature of their roles from the original.

While it was understandably pegged as a big budget horror film upon release (and compared to the same year’s “The Silence of the Lambs”), “Cape Fear” is also full of film noir elements. Bowden is the unreliable protagonist who, at one point, must literally wash the blood off his hands. The intense rainfall of the finale (indeed, a “force majeure” that Bowden correctly states and foreshadows) is another film noir trope.

Thematically, this is akin to Sam Peckinpaugh’s “Straw Dogs” (1971) asking you, the viewer, how far can you be pushed before you fight back in a way that you can never walk away from?

Like the original (which is worth seeing for the performances but less than a classic), this explores the fear of sexual violation, though Scorsese and screenwriter Wesley Strick take this much further than director J. Lee Thompson could in ’62, though not in an exploitative or irresponsible way.

If anything, the elevated sound effects, bad guy one-liners and elaborate physical effects in the big finale partially distract from how vile Cady’s plan is and how he intends to carry it out. The fear of rape goes into the subtext as well- note how Danny’s teddy bear, of all things, is used as bait to ensnare Cady.

RELATED: Scorsese’s ‘Irishman’ Refuses to Meet Our Expectations

The internal chaos of “Cape Fear” is also explored, as Bowden is weary of a “big bad wolf” like Cady infesting his daughter’s environment but, as evidenced by how he teases Lori with an emotional affair, Bowden is also a part of the problem. Cady is clearly the greater threat but Bowden, in his own way, is another type of monster.

“Cape Fear” may have been a “mainstream” film for Scorsese (in the same way he was hired to make “The Color of Money” and turned it into a rousing, adult-minded box office and critical hit), but it’s not a sell-out.

In fact, viewed today, it plays like an elaborate but personal movie. Even the use of special effects (like Cady’s appearing on the Bowden’s wall while giant fireworks light up the sky) seems deliberately artful.

Scorsese’s overall body of work far outshines his classic mobster films and demonstrates a filmmaker who can create authoritative, passionate and personal films in any genre. This was an out-of-left-field choice for Scorsese at the time (in the same way his subsequent “The Age of Innocence” and “Kundun” were the same decade) but, like his best films, it’s a masterpiece and every bit as essential as gangster films.

This is one of my favorite movies of all time which is why I decided to do this scene. Robert Deniro won best actor and Juliette Lewis won supporting actress at the academy awards. It was Directed by Martin Scorsese. Enjoy this scene that I did with Nick Nolte. #CapeFear pic.twitter.com/CyIVR4Jdtz

— Pauly Shore (@PaulyShore) March 23, 2021

Baker’s Detective Kersek has this pivotal monolog during the second act: “I want to savor that fear. The South evolved in fear, fear of the Indian, fear of the slave, fear of the damned Union. The South has a fine tradition of savoring fear.”

What is he talking about?

Specifically, the kind of things that make up Cady’s lineage, the values of his “white trash” background and how his time in prison has elevated his intelligence but also his most repulsive qualities. Most of all, Kersek is speaking about the frightening possibility that we are all capable of committing the worst things imaginable.

Fear can be a weapon used to distract and alter the perspective of the intended victim — Cady creates fear in Bowden, both in what he plans to do to his family and by revealing just what Bowden did to deserve this.

Cady is a Freddy Krueger-like reminder of the sins of the past (this extends to the character’s final appearance), as well as a boogeyman whose mission is tainted with righteous anger. Cady embodies all that is awful about our past and the fear that we will get what we deserve- Scorsese and De Niro make this monster of “justice” deeply unsettling, just one reason why “Cape Fear” is among Scorsese’s greatest achievements.

The post How Scorsese’s ‘Cape Fear’ Did More Than Trump the Original appeared first on Hollywood in Toto.