A Field Guide to North America’s Wild Crops

When I was a child in New Jersey, summer meant berry picking. As the wild raspberries ripened, the emerald woods around our house became spotted with bright bursts of deep purple. We would plunge through the brambles to collect enough juicy, tangy-sweet berries to make a pie. We didn’t realize that the local black raspberries were a cousin of the plumper, red variety we bought at the grocery store. We just knew that they were delicious.

These berries are just one of the many species of wild or feral edible plants dotting the North American landscape. Called crop wild relatives, they’re the genetic cousins of the strawberries, hot peppers, and hazelnuts found in grocery stores around the world. Many of these plants, such as chiltepins, a tiny, fiery Sonoran desert pepper from which dozens of pepper cultivars were bred, remain an important foraged food for Indigenous people. Others, like apios, were once cultivated by Native Americans; apios is no longer widely cultivated due to the European colonial destruction of Native food systems, but the species now spreads freely across eastern North America as feral plants. Species such as wild strawberries, which dot fields and forests from Oklahoma to Ontario, are native plants that agricultural breeders crossed with other species to create the produce at your local supermarket.

Take a walk through a local nature preserve, neighborhood park, or even backyard, and you can see some of these species today. They’re living artifacts of human agricultural history, carrying the genetic evidence of thousands of years of adaptation to their local environments. In the past few decades, scientists have taken a renewed interest in wild crop relatives, as they contain traits that can potentially make our food system more resilient in an unstable climate.

“Even a decade ago, people were like, ‘This is kind of marginal,’” says Colin Khoury, a crop-diversity specialist affiliated with the International Center for Tropical Agriculture and Saint Louis University. “Now it’s totally mainstream.” That’s largely thanks to Khoury’s network of scientists and seed banks, who document, collect, and store crop relatives for research. But it’s also thanks to increasing public passion for sustainable food systems and a renewed interest in native plants.

Public interest in these species is critical, as habitat destruction and climate change increasingly threaten crop wild relative populations across the world. In December 2020, Khoury and several colleagues published an analysis of the conservation status of more than 600 species in the United States, the product of a decade of effort. They found that half of these species may be endangered in their natural habitats, and another 28 percent may be vulnerable. Khoury hopes to eventually enlist citizen scientists to find and raise awareness of the plants.

That’s where you come in. Khoury hopes that increased public interest in crop wild relatives and their importance to food security will lead to greater momentum to protect them. Below is a selection of species with unique histories and cultural meanings. See if you can spot some in your area. Not only are they fascinating, but many are delicious.

A Note On Conservation

None of the plants on this list are considered threatened or endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List, the preeminent global database. But they are all, says Khoury, harmed by the effects of habitat destruction and climate change. And they’re all deeply meaningful to the people, mostly Indigeneous Americans, who have stewarded them for generations. “Wild plants have connections to culture,” says Khoury.

Before foraging, it’s important to understand the cultural and ecological context of the species you’re taking. “When you approach foraging or harvesting, you try to understand: ‘What is this being doing? If I go in and take something, is it going to be okay?’” says Khoury. “That does require a little learning about it.” Some species, such as the pawpaw, can safely be picked wild in much, but not all, of their range. Others, including the chiltepin and tepary beans, are best to grow or buy from local suppliers rather than picking yourself, and non-Native people should never forage on tribal lands without permission. Still others will be difficult to find in enough abundance to forage in your local ecosystem. We’ve included notes on the conservation status of each species.

Khoury suggests using the principles of the Honorable Harvest, as presented by Robin Kimmerer, a plant ecologist and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Kimmerer describes the Honorable Harvest as “the canon of Indigenous principles that govern the exchange of life for life.” They include asking permission from the life you’re about to take; never taking the first or last of something; using everything that you take; and sharing what you’re given.

California Hazelnut

Corylus cornuta var. californica

Closest cultivated relative: European hazelnut

Range: Northern California and the Pacific Northwest

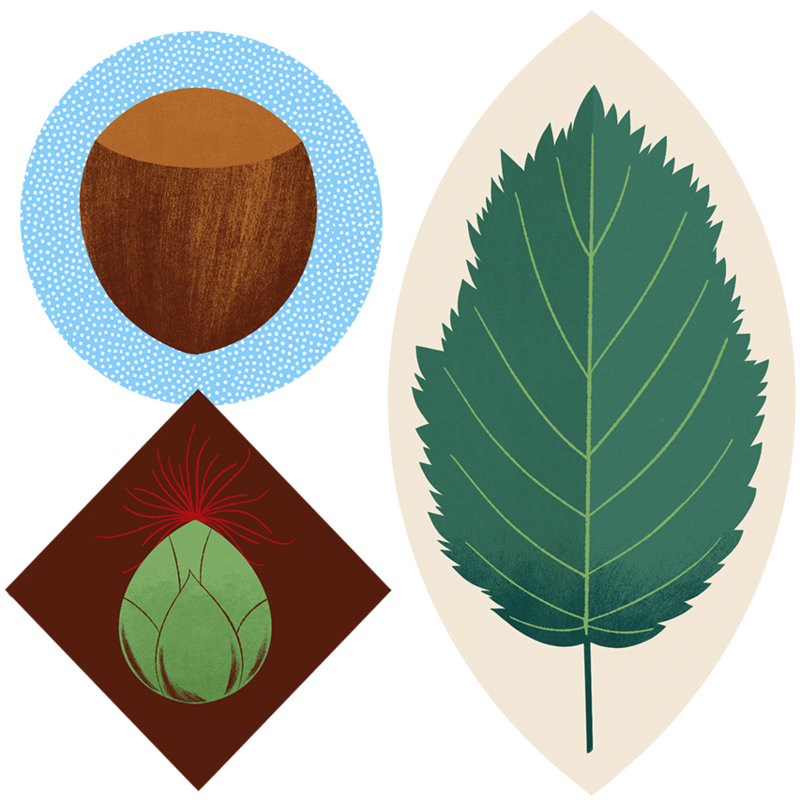

How to spot it: A California Hazelnut bush; a late-winter catkin; a developing nut.

During late winter, when other plants are just starting to bud, the California Hazelnut unfurls its long, yellow catkins. This is the “male” part of the hazelnut shrub, which is most often found clinging to roadsides, stream beds, and the edges of yards.

A relative of the commercialized European Hazelnut, California hazelnuts have long been used by many Native groups in the Pacific Northwest, who roast them, eat them raw, grind them into cakes, or boil them for oil. Today, they’re one of several native American species scientists are eying for commercial development, to help remedy a hazelnut shortage caused by deadly fungus and global hunger for Nutella.

If you spot those late-winter hazelnut catkins, note the location. When you return in July, the undersides of the sawtooth leaf clusters will be heavy with nuts, which are covered in a fuzzy coating, called an involucre. Twist the involucre off (leave the twig), dry the nut packets in a cool place for a few weeks, peel, shell, and eat. California hazelnuts are smaller than their cultivated cousins, but just as tasty. Try them in a maple-hazelnut sorbet, a recipe created by The Sioux Chef’s Sean Sherman, or simply roast and snack.

Pacific Crabapple

Malus fusca

Closest cultivated relative: Apple

Range: Northern California to Alaska

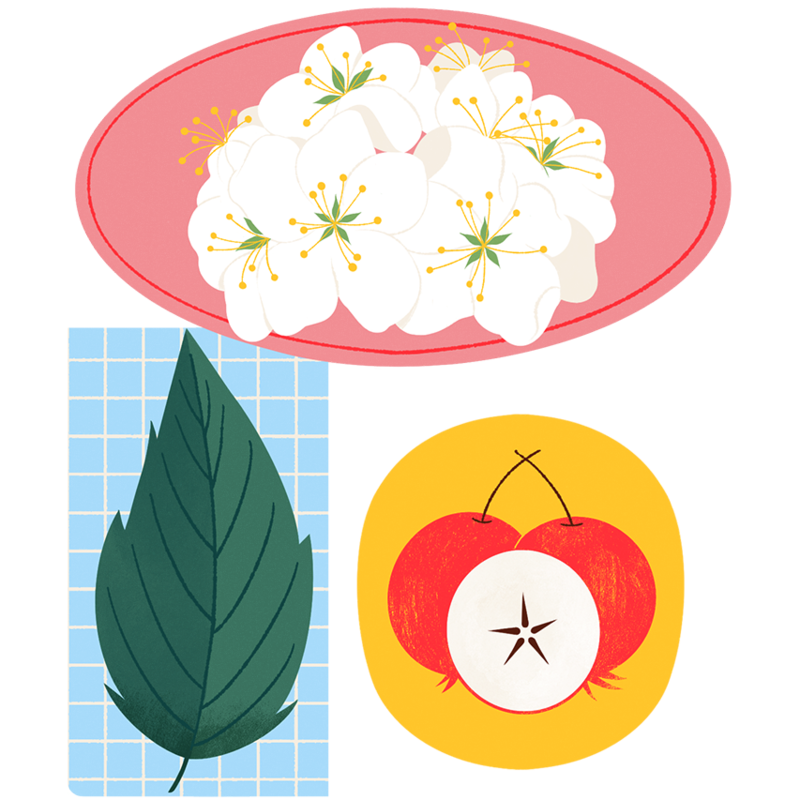

Photos for Identification: Crabapple leaves and flowers; crabapples.

The domesticated apples we eat today originated in the mountains of Kazakhstan, and Europeans brought their seeds in their early colonization of North America. Yet there already were apples in North America: crabapples, whose blush-pink and crimson exteriors and bitter-firm flesh decorated wizened trees across the continent.

The Pacific crabapple is one of these native species. It grows happily in moist soils along streams and in forest clearings. In April, white-pink blooms bubble from its boughs, while small, firm, reddish-pink fruits emerge by midsummer. Their flesh is bitter, but perfectly edible. Try pickling them, making them into crabapple goat-cheese ice cream, or baking crabapple dessert bars.

For the past few years, scientists from Oregon State University and Northwest Meadowscapes have been experimenting with using Pacific crabapple rootstock in commercial cider-apple production, in order to create crops better suited to the Pacific Northwest’s climate. Initial results show the rootstock is compatible with several commercial apple cultivars.

Chiltepin

Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum

Closest cultivated relative: It’s the progenitor of most edible peppers (jalapeno, poblano, mirasol, cayenne, bell, etc.) except habanero, tabasco, aji, and a few others.

Range: Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Texas

How to spot it: Ripening chiltepins.

If you love peppers, thank bird poop. Birds don’t taste the compounds that make peppers spicy, so they gobble up the fruits, dropping seeds as they fly. That’s good luck for hot peppers, which first evolved in Central or South America (some scientists say Brazil) and likely had their seeds carried by birds as far north as the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. More than 7,000 years ago, Indigenous people in East-Central Mexico domesticated the plant.

Many of the resulting pepper varieties can be traced back to the chiltepin, a scraggly bush with tiny, intensely orange-red and crimson berries. It still grows wild in the Sonoran desert, and is the oldest and only wild pepper in the United States. It clings to the sides of steep slopes, bunching with other brush. While cultivated chiltepin seeds are commercially available, many communities forage the peppers each September and October. Noah Schlager, Conservation Program Manager at Native Seeds/SEARCH, recommends supporting these Indigenous collectors, who often sell in local shops, or purchasing seeds for home cultivation.

Clocking in at up to 100,000 spiciness units on the Scoville scale (poblano peppers range up to 8,000), the peppers have a sharp heat that hits hard and fades quickly. Try them in this home-make yogurt-cheese recipe or get right to the point with a chiltepin salsa.

Tepary Beans

Phaseolus acutifolius

Closest cultivated relative: Cultivated tepary beans; lima beans

Range: Arizona, New Mexico, Texas

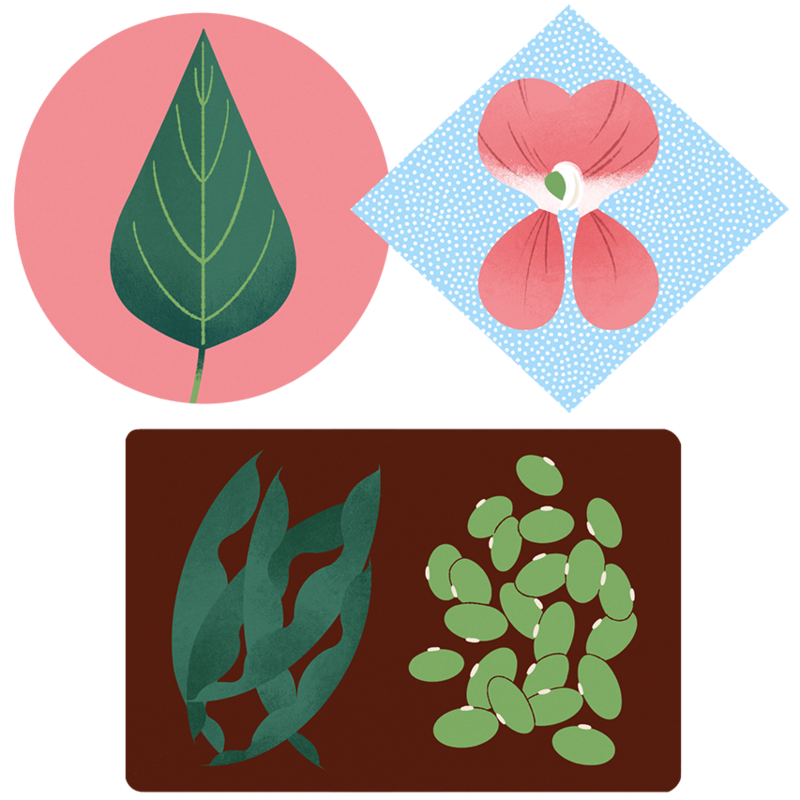

How to spot it: Tepary bean flower; tepary bean leaves and pod; dried tepary beans.

Around 6,000 years ago, Indigenous people in the Sonoran Desert began cultivating a wiry bush: the tepary bean. A drought-hardy, densely nutritious food, tepary beans are so important to the Tohono O’odham, one of several Sonoran desert peoples who highly value them, that they have a legend that describes the Milky Way as white tepary beans speckled across the sky.

Indigenous farmers grow tepary beans in the Southwest United States and Northern Mexico. You can purchase seeds for cultivation or buy tepary beans from Native producers; they’re excellent cooked with other desert foods such as prickly pear and nopales, and even in tepary-bean chocolate brownies.

With some exceptions—the Serí people from Mexico’s Tiburón Islands collect and eat larger wild varieties—the wild bean is not suitable for cooking, says Schlager. But you can spot wild beans in desert washes in Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Texas by their delicate, pink-purple blooms, which blossom after the summer rains. Be careful not to disturb them.

Wild Strawberries

Fragaria virginiana

Closest cultivated relative: Strawberries

Range: Widespread from Newfoundland to Oklahoma

How to spot it: Strawberry leaves and flowers; strawberry fruit.

Growing up, Lauren J. Mapp, a journalist and member of the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka tribe with a culinary background, travelled to the Akwesasne reservation with her family each June to celebrate the strawberry harvest. “My favorite festival throughout the whole year was the strawberry festival,” she says.

The festival marked not just the berry harvest, but creation itself. In the beginning, says Mapp, there was a water world and a sky world. One day, a Sky Woman fell into the water world. She landed on the back of a turtle, which became the landmass that English speakers call North America. The Sky Woman had a daughter. When the daughter eventually died, five plants grew from her body: tobacco from her head, corn from her breasts, beans from her kidney, squash from her navel, and strawberries from her heart.

Today, wild strawberries remain abundant across traditional Haudenosaunee lands, as well as across a broad swathe of eastern North America, from Ontario to Georgia. In the 1830s, breeders crossed these strawberries with a wild South American variety to produce the strawberries we buy from the grocery stores today.

You may have seen the white, star-like blooms or bright-red berries nodding from long stems between club-like leaves in meadows and forest clearings. This summer, feel free to forage—the berries are in the least-threatened conservation category—and try Mapp’s recipe for traditional strawberry drink, sweetened with maple sap (not syrup), to celebrate the season. If you can’t find maple sap, which is what the tree gives before it’s boiled into syrup, Mapp suggests cane sugar.

Pawpaw

Asimina triloba

Closest cultivated relative: Custard apple, sweetsop, soursop, cherimoya

Range: Widespread from Ontario to southern Florida, as far west as Nebraska

Conservation note: The USDA has labelled it endangered in New Jersey and threatened in New York, so local experts advise to only pick from cultivated trees in those areas. “Fortunately, collecting the fruit of a pawpaw tree does not harm the tree itself,” says Sara Bir, an author, chef, culinary educator, and pawpaw expert. “As long as you don’t pull down the branches or mangle the tree, it’ll keep on growing.”

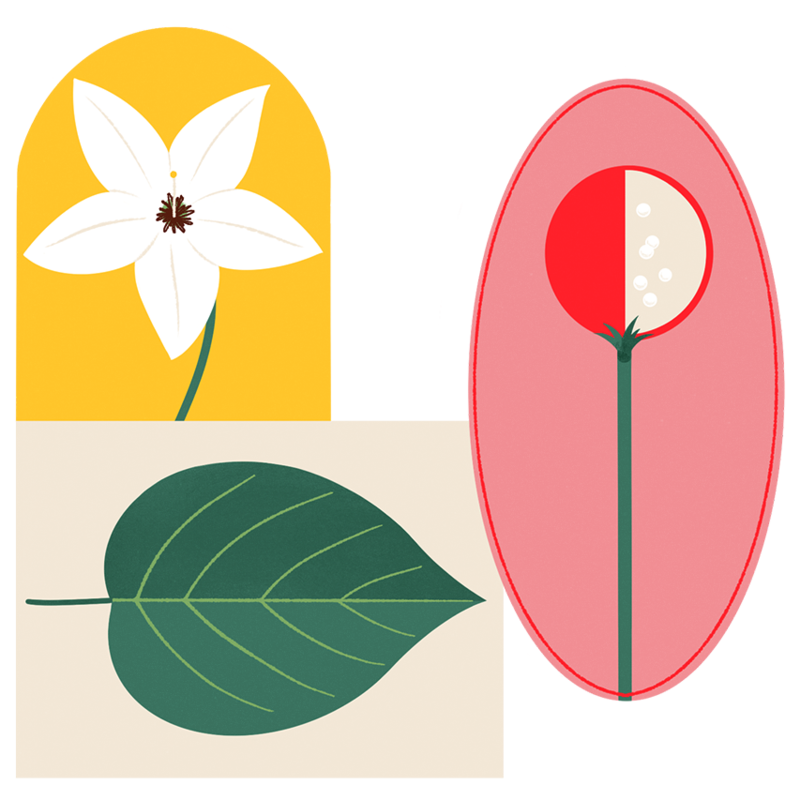

How to spot it: Pawpaw tree; pawpaw flower; pawpaw fruit.

Before humans came to the continent, North America was so warm that tropical trees crept up as far as modern-day Canada. When the climate cooled again, most of these trees, except the pawpaw, retreated. Scientists theorize it was then spread by giant mammals—sloths, mastodons, mammoths—who ate and pooped the seeds. When people came, and giant mammals disappeared, the pawpaw became a sweet food source for human beings.

Related to the custard apple, the pawpaw tree has glossy, dark green leaves and fruits with a plump, sweet flesh that tastes like banana, mango, and egg custard. Indigneous people and European colonizers enjoyed them. Yet for the past century, they’ve been largely absent from the mainstream American diet. That’s partly due to the rise of industrial food production. Pawpaws reach their flavor peak for a few sweet days in September or October, depending on your latitude. Pick them too early or too late, and they’re astringent, making it nearly impossible to ship them fresh over any distance.

Pawpaws like to live on the edges of forests or in clearings, as they need access to both full sun and patches of shade. They can propagate themselves by sending up suckers from their roots, which become what appear to be new trees (but are actually clones), so chances are if you find one pawpaw tree, you’ll find a whole clearing of them. They may not all have fruit, however. “In the wild, pawpaw trees can be fickle,” says Bir. “They don’t produce fruit every single year because they have another means of spreading.”

You’ll recognize them by their glossy leaves; their pink, rancid-smelling flowers (they need flies to pollinate); and their oblong fruits that resemble green mangoes. You can also find them at some farmers markets. Enjoy them as a luscious hand fruit, or one part of a kick-ass pawpaw pie or chocolate pudding.

Potato Bean, Hopniss, American Groundnut

Apios americana

Closest cultivated relative: Potato bean was historically cultivated by Native Americans; some farmers also grow it in Japan

Range: Native to eastern North America from Florida to Nova Scotia, and west to Texas and Minnesota.

How to spot it: Apios leaves and vines; a close-up edible flower; apios bean pod; a string of apios tubers.

The potato bean, also called American groundnut, apios, or hopniss (its Lenni Lenape name), is a perennial vine that grows abundantly in moist, forested areas, often near streams. Its shoots are crunchy and mildly pea-flavored; its flowers—ornate crimson-pink folds that emerge in mid-summer—are a lovely salad ingredient; its beans can be boiled into a tasty soup. Then there’s the “potato” itself: the starchy, walnut-sized tubers that grow, like strings of pearls, along the plants’ long roots.

Cooks can use these tubers similarly to a potato: They make excellent chips, and the Menominee Indigneous people of present-day Wisconsin historically enjoyed them with maple syrup. The crop was likely domesticated by Native Americans at one point, and early European colonists in Massachusetts used it as a food source. Despite this history, the species has never been adapted for commercial production—partly because the tubers’ two-year growing cycle isn’t amenable to industrial monoculture. There have been several recent pushes to domesticate the potato bean for commercial production, though none have been successful so far.

Once you find the plant in the wild, however, you’ll likely stumble upon a robust population, as the roots tend to spread wide. Forager, cookbook author, and potato-bean-lover Sam Thayer says that the potato bean is “quite common and widespread over a very large geographical area,” so foraging it shouldn’t be a problem, pending normal due diligence. Eager home gardeners can also grow the tuber, either from specialty shop cuttings or propagation from wild plants.

The only drawback to this workhorse of a food: According to Thayer, a small percentage of people who try the tuber become ill, possibly because of an allergic reaction. But this hasn’t stopped many other native food lovers from enjoying hopniss dishes, including this recipe for potato-bean skordalia, a take on the mashed-potato-like Greek dish.

Wild Hops

Humulus lupulus, various varieties

Closest cultivated relative: Domesticated hops

Range: Different variations can be found across the United States; there are particular concentrations in New Mexico and New York state.

How to spot it: The New Mexican variety

Every year, New Mexican craft brewers head to the hills. There, wild hops hang down in vines with heavy, resinous strobiles (cone-like structures). They’re a local, wild variant of the plant, which has been a key ingredient in beer brewing since at least the 800s. Hops are native to both Eurasia and the Americas, but for centuries, brewers eschewed wild American varieties for imported cultivars.

That’s changing in several regions, including New Mexico; the Pacific Northwest, where the bulk of cultivated hops are currently grown; and New York state, which was the center of the American hops industry until downy mildew wiped it out in the 1890s. In New Mexico, brewers are using foraged wild hops to create craft brews with piney, fruity, and fragrant flavors. In New York, trade groups are investigating local discoveries of feral hops, the escaped remnants of the long-ago hop industry, as well as wild hops.

You can find New Mexican wild hops in desert mountain clearings where trapped moisture creates lush microclimates. The New York varieties often hang out at the edges of agricultural fields and even on fence posts, likely near where they used to be grown. Home brewers can use wild hops in their creations, like this wild-hops honey ale. The young shoots are also edible and happen to be one of the most expensive vegetables in the world; here’s a recipe for a hops risotto.