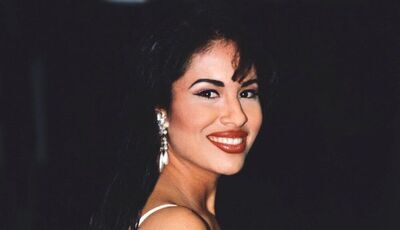

On Growing to Love Selena

I’ve always had trouble waking up. My parents would take turns yelling my name, trying to get me up for school. (Since I was named after the Katherine Ross character from “The Graduate,” they often found this amusing. “Elaaaaaaine!”) One morning, after a few rounds of shouting my name and even turning on my bedroom light, my father came into my room and turned up the volume to my radio. It was Selena’s “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” and I could hear it playing throughout the house.

“You have to come to the kitchen,” my dad said, his voice booming. “Your mother’s doing the Cumbia.” It was an image I couldn’t resist and something I needed to see. I dragged myself out of bed and lumbered to the kitchen where I saw my mother giggling and dancing to the Tejano tune. She called me over and taught me the basic steps. Before the song ended, we were dancing to one of Selena’s most famous Cumbias. Whenever I hear this song and break out my dance moves at a bar or any friend’s wedding (pre-pandemic, obviously), I think of this particular morning. Since then, both of my parents have passed away and it’s a memory I cherish because, like Selena, their meaning in my life after their death continues to grow.

If you’re from Texas, you know exactly where you were and what you were doing when Selena died on March 31, 1995. I was working at a friend’s graduation supply company in my hometown of San Antonio when the office manager announced the news. Selena had been shot at the Days Inn motel in Corpus Christi after arguing with Yolanda Saldivar, the president of the singer’s fan club who helped run her boutiques. My best friend and I jumped into her purple Ford Ranger and drove by Selena Boutique & Salon, a store she’d opened in San Antonio a year before. By the time we got there, a small crowd had gathered in the parking lot where they sang her songs and mourned her loss. My best friend and I didn’t own any of her CDs, so it felt intrusive. Instead, we paid our respects and drove on.

I may not have been a superfan before she died, but growing up in South Texas, you couldn’t help but know who she was. There was the store, of course, and her band Selena y Los Dinos frequently performed across the state, and her music often played on local Top-40 radio. But it was after her death that her star truly began to rise.

A year had passed when word began to spread that Hollywood was making a movie about Selena. This was long before social media, so finding out something like this meant reading about it in the newspaper, or hearing about it on the radio or local news. Rumors became facts when it was officially announced that parts of the movie would be shot in San Antonio. It was a big deal for what was considered, at the time, a sleepy town a few hours north of the Border. There was a call for extras to go to the Alamodome, the city’s football-sized arena, where the movie planned to recreate Selena’s famous Houston performance where she danced in her purple-sequined outfit in front of more than 66,000 people. The city was abuzz. Throughout the fall of 1996, people talked about spotting film crews and witnessing scenes. In 1997, a week before the two-year anniversary of her death, the movie was released. I have no idea how it played across the country, but in San Antonio, it was an event. The audience cheered for her, sang with her and cried for her once again.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I now realize I was entranced when I saw the movie because it was the first time I ever saw anyone on the screen that looked and acted like me. Clearly, I do not look like JLo and I’m not a Grammy-winning singer, but for the first time, there was a curvy woman with dark hair and cinnamon-tinted skin—and she was the star! She was a hard-worker and rewarded for it, and finally on the big screen, I saw someone that I could aspire to be. “Representation Matters” has since become a hashtag, but the meaning behind it is real, substantive and impactful. It’s fascinating how that works.

Since the movie, her star wattage has only gotten brighter. As each year ticks by and milestones are marked with unreleased music and never-seen-before images, her diehard fans’ desire to consume more of her appear never-ending. Someone once told me that missing a loved one doesn’t diminish with time like a bad habit you’re trying to break. Instead, it’s like trying to quench a thirst that’s never satisfied. Through the years, her image has appeared on everything from convenience store cups to pillows and blankets. Last year, MAC Cosmetics released its second limited collection of lipsticks and eyeshadows featuring her name, which promptly sold out. Netflix released Selena: The Series last year to much fanfare and was given a second season. At this year’s Grammy Awards, she was recognized with a Lifetime Achievement Award. As we marched closer to the date of her death, I saw dozens of stories calling her an icon, which is true. But she’s more than that. She’s a beacon whose light made it possible to celebrate a Tejana in all of her bedazzled glory across cultures. It’s because of her that I’m unapologetically overdressed for any event, and wearing bright, red lipstick and oversized hoop earrings.

My job has taken me from California to New York and there is something to be said about seeing her image everywhere I travel because not only does it remind me of home, but also honors my heritage. A few years ago, I visited some Tex-pats living in California. It was the holidays and my friend said she had a gift for me. It was a limited-edition reusable tote bag with Selena’s image and the word Siempre, or always. I felt like I’d won the Golden Ticket and I danced around the house with the Selena bag over my shoulder. When I traveled back to my current home in New York, I took my bag on a trip to the grocery store. It wasn’t long before a woman stopped me and asked, “Did you get that from HEB?” Not only was I thrilled to meet a fellow Texan who appreciated the cult of HEB, but I also met a stranger who loved Selena—once again bringing all walks of life together.

Elaine Aradillas is the crime reporter for People Magazine, and an adjunct professor at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University.