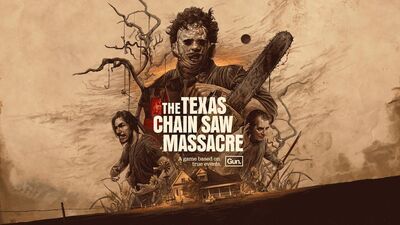

Texas Chain Saw Massacre Game is a Promising Tribute to the Bloody Original

Half a century has done little to dull the potency of Tobe Hooper’s 1974 shocker, “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.” Makeup artist Tom Savini is fond of saying that old films aren’t really old if you haven’t seen them yet. And I hadn’t seen the original “Texas Chain Saw Massacre” until six years ago, shortly after discovering the online multiplayer game “Friday the 13th.” That project, by Gun Media and IllFonic, revitalized interest in the dormant Jason Voorhees property while also helping popularize the “asymmetrical horror” subgenre, which has its roots in video game series like “Aliens vs. Predator” and “Splinter Cell.” Gun’s latest—a collaboration with developer Sumo Nottingham—aims to give Hooper’s genre classic the same treatment as “Friday the 13th: The Game” but largely avoids the trap of having too much in common with the company’s earlier hit.

The original 1980 “Friday the 13th” is in many ways the cinematic progeny of the 1974 “Texas Chain Saw Massacre” and of John Carpenter’s “Halloween,” but Hooper’s film, co-written with fellow Texan Kim Henkel, has different things on its mind. It opens with images of decomposing human remains, more upsetting than anything in “Halloween” or the original “Friday the 13th,” while a radio broadcaster delivers the news. Someone has been digging up graves at local cemeteries; there’s been a fire, an outbreak of violence, a suicide, and a suicide attempt. A full moon dissolves into a shot of a roadkill armadillo.

There’s an erratic, hallucinatory quality to the movie’s editing, especially early on, but that recurring image of the full moon holds it all together. The story follows a group of young people road-tripping in a van. One of them, Pam (Teri McMinn), reads aloud from a book on astrology: the planet Saturn is in retrograde, she says, setting a scene for karmic debts to be paid. Another road-tripper, Franklin (Paul A. Partain), spots an old-fashioned slaughterhouse along the road just as they encounter a terrible smell. The conversation in the van shifts to the brutal methods used to butcher cattle at such places—sledgehammers striking skulls “two or three times”—as the camera lingers, in close-up, on many of the animals in question. Shortly after, the group picks up a wild-eyed hitchhiker (Edwin Neal); Franklin jokes about him being a Dracula. “My family’s always been in meat,” says the hitcher proudly before his talk of head cheese puts the kibosh on the subject. “A whole family of Draculas,” Franklin observes.

With the “Texas Chain Saw Massacre” video game, Gun and Sumo have made the Slaughter Family the stars of the show. Veteran actor-stuntman Kane Hodder picks up the chainsaw for the first time since his stunt work on 1990’s “Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III.” Edwin Neal provides the voice of the Hitchhiker, some 50 years after wrapping up the Hooper picture. Kristina Klebe, who played Lynda in Rob Zombie’s remake of “Halloween,” delivers a chilling voice-over performance here in the role of “Sissy,” one of two new members of the Family. She’s joined by Damian Maffei, who voices Johnny Slaughter, a brother absent from the films. Actress Scout Taylor-Compton, known for portraying Laurie Strode in Zombie’s “Halloween” entries, plays SoCal surfer type Julie Crawford in the game—along with a significant amount of performance capture.

There’s a fair bit of narrative backbone for an online multiplayer game where one group of players tries to hunt and kill their four “Victims.” Currently, the roster of playable Victims includes five original characters, and they’re all in this mess to help their friend Ana Flores (voiced by “My Adventures with Superman”’s Jeannie Tirado). Ana’s sister, Maria, is a student photographer who’s gone missing in Muerto County during wildflower season. So the camera we see the Hitchhiker using in the original movie is Maria’s, according to Gun and screenwriter Henkel, and the campsite in the film is further evidence of this new cast having been there. It’s a cleverly-situated prequel with several months of wiggle room. Not bad for a continuity that, historically, writers have treated with as much respect as a small-town stop sign.

From the jump, the game’s design is a departure from “Friday the 13th,” though not to such an extent that it’s likely to alienate Gun’s core audience. Where “Friday the 13th” pits the supernatural, superstrong Jason against seven other players, “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” adjusts the formula: three members of the Family versus four Victims. And Leatherface, whose chainsaw grants him the unique ability to cut through various obstructions around the map, must be present in every match.

I’ve played “Friday the 13th” with much of the same group since 2017, and a part of me has always relished being Jason. There’s a certain fantasy in being a force of nature like that, fighting for control of the map, sabotaging the phones, chasing cars, and making sure everybody’s having a good time. When there’s one killer, whoever plays Jason can show mercy early in the game; they can prioritize more skilled targets over less experienced players. My “Friday” buddies seem to enjoy it when I play Jason, even if none of them escape with their lives by the time the match is over.

In my time with “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” I seem to prefer the Victims. Granted, comparing one week to the 549 hours I logged in the earlier game is hard. But I suspect it has to do with the numerous ways Gun and Sumo have improved upon so many other aspects of the experience. Stealth mechanics feel fairer and more skillful than sneaking around in similar games; the “Splinter Cell” influence sometimes shines through without complicating things. Minigames, where you solve a brief puzzle to pick a lock or repair a fuse box, are much more precise and player-driven than their “Friday the 13th” equivalents, which sometimes meant holding down the A button and hoping Jason wasn’t within arm’s reach. For all that “Friday the 13th” got right, this is a superior piece of software in the most formal sense.

There are two areas where “TCM” distinguishes itself from other asymmetrical horror games. The first is that Gun and Sumo understand—like Hooper, Henkel, cinematographer Daniel Pearl, and crew before them—that this setting is one of immeasurable beauty. It’s only when you add human beings, those meat eaters and online gamers and horror fans, that things get mucked up. In the film, Leatherface takes his chainsaw to one of his victims, and the camera cuts away to a shot of sunlight beaming through the spinning sails of an old windmill. There’s also a rundown house overgrown with green vegetation early in the movie.

The game embraces these images of nature’s power. The thickets, the wildflowers, and even water can be your salvation. Meanwhile, metal gates, generators—yes, the ever-present revving of the saw—recall that discussion of the slaughterhouse from Hooper’s opening act. Often, a locked door is all that stands between you and the open land.

The other thing that makes this a fun game to play is it can scare the hell out of you. It’s nice to take in the heavenly orange skybox during the daytime, maybe put on a podcast or some seventies rock. But there’s nothing like being on a nighttime map and rounding a corner to find Sissy standing there, barefoot in a black dress, moonlit straight razor in hand, as her gaze finds yours.

Available now. A review copy of this title was provided by the publisher.