The Royal Hotel

In her debut narrative film, the workplace horror “The Assistant,” writer/director Kitty Green took the most ordinary setting and made it a tense, nauseating psychological thriller. Pairing again with Julia Garner, her follow-up “The Royal Hotel,” co-written with Oscar Redding, plays like a Gen Z twist on the Australian classic “Wake in Fright.”

While Green and Redding’s initial inspiration was the 2016 documentary “Hotel Coolgardie,” which explored the volatile sexism faced by twenty-something Finnish packbackers who came to work in an isolated pub near a mining town in the Australian Outback, there is equally as much of Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 cult film in its DNA. Similar to how “Wake in Fright” explores the tumultuous, violent, and frenzied alcohol culture of the Outback from the point of view of a mild-mannered male school teacher (Gary Bond) who slowly succumbs to its madness, Green sets her focus solely on how this violence, which can manifest physically, emotionally, and psychologically, affects the well-being of young women.

Garner plays Hanna, who is slightly more responsible than her bestie, Liv (Jessica Henwick). The duo, who claim to be Canadian because “everyone loves Canadians,” are on holiday in Australia when they become strapped for cash due to Liv’s spending (and most likely her drinking.) They take a temporary live-work job at the titular Royal Hotel, a desolate, faded pub that takes a train, a bus, and a very dusty car ride to get to. It’s the only waterhole for miles—it appears to be the only building within a few hours’ drive.

The pub is run by owner Billy (Hugo Weaving) and his sometime partner Carol (Ursula Yovich), whose own bittersweet relationship is punctuated by bursts of violence. Weaving deftly walks that fine line that high-functioning alcoholics often find themselves on, between someone rough but charming and someone who is terrifyingly violent. Yovich plays Carol as a woman who has made a prickly peace with her situation. There was probably love once there between her and Billy, but now she’s mostly there to keep him from drinking himself to death and keep the crusty hands of the mine workers off the girls he hires to keep the pub open.

The fraying relationship between Hanna and Liv is tested further as they become friendly with the locals. There’s Matty (Toby Wallace, bringing the same natural dangerous charm he did to his breakout role in “Babyteeth”), who has a sweet spot for Hanna. There’s Teeth (James Frecheville), whose bumbling sweetness hides a troubling obsessiveness. And there’s Dolly (Daniel Henshall), whose menacing gaze at the end of the bar gives him the air of a lion waiting out his prey.

While Liv embraces the men’s work-hard, party-hard mentality, Hanna remains more reserved, always aware of the danger lurking behind a drunken man’s charm. “My mom drank,” she says at one point, the pregnant pause indicating she’s seen her fair share of how alcohol can change someone in an instant. Even when she does let her guard down a little, her thoughts are always on Liv’s safety and the perilous situation they’ve found themselves in.

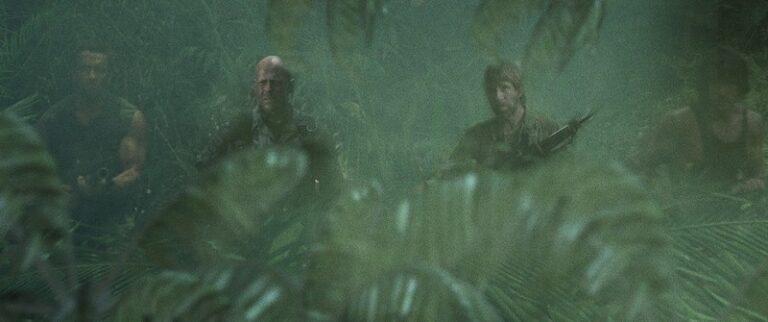

Again, like “Wake In Fright,” Green teases out the tension slowly. At first, everyone’s drunken revelry is just overly boisterous. A glass broken out of careless abandon. A cruel joke told for a harmless laugh. A firecracker in the distance lighting up the night. She fills the frame with happy bodies in motion, laughing, joking, and drinking as the only entertainment in town. But slowly, the situation becomes more threatening. A large, drunken man in the hallway staring into their bedroom. An insult hurled with the cutting force of a sharpened blade. A chair thrown in controlled, intimidating violence. The bodies in the frame grow more numerous, their laughing and movements more ominous and brutal.

While Green excels in building the social economy of this world and is a master at slow-burn tension, not all of the characters work. Garner, Weaving, Yovich, and Wallace all find deeper psychological layers to their characters through body movements or certain knowing looks. Unfortunately, what makes Hennwick’s Liv tick never quite comes into focus. She makes one terrible decision after another, but other than a line about Australia being the furthest away she could get from her home, the film never spends enough time focusing on her for any of it to make emotional sense. It’s also never very clear how, or sometimes even why, Hanna and Liv are even friends.

Despite this and an abrupt ending that cheapens the richly drawn complexity that came before it, “The Royal Hotel” remains a chilling and tense examination of the Outback’s toxic alcohol-fueled culture. Green continues to establish herself as an insightful chronicler of the minor yet devastating terrors of violent masculinity that many women endure everywhere they go.

This review was filed from the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. “The Royal Hotel” opens in theaters on October 6th.