Roger Ebert on the Films of Martin Scorsese

Just as we did with Christopher Nolan this summer, we thought we’d use the release of a new film by Martin Scorsese (“Killers of the Flower Moon”) to look back on the many times that Roger Ebert wrote about the work of this undeniable master filmmaker. Of course, Roger and Martin’s relationship is well-documented, and their careers are closely tied together because of it. But it’s still enlightening to go back and actually look at how Roger approached each of these films. Below, you’ll find a link to all of Roger’s reviews of Scorsese’s films, along with the reviews since Roger’s passing written by Matt Zoller Seitz and Brian Tallerico.

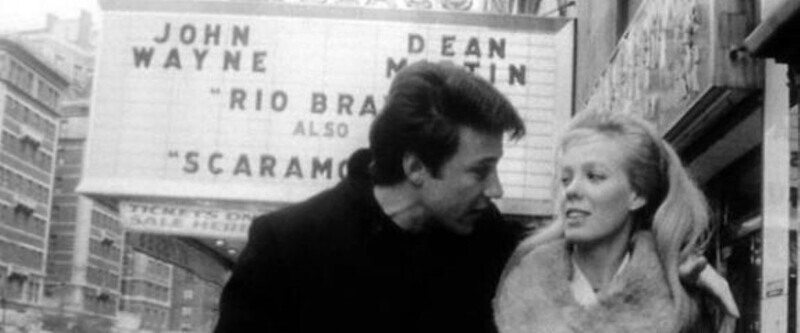

“Who’s That Knocking at My Door?”

“This is essentially a director’s film, but the performances are as good as we could possibly hope. Harvey Keitel as the boy, and Zina Bethune, former star of the TV series, The Nurses, as the girl, find exactly the right tone together. And Lennard Kuras, who plays the hero’s best buddy, is so good all you can say is, yes, guys like that are exactly like that.”

“Boxcar Bertha”

“Scorsese remains one of the bright young hopes of American movies. His brilliant first film won the 1968 Chicago Film Festival as “I Call First” and later played as “Who’s That Knocking at My Door?” He was an assistant editor and director of “Woodstock,” and now, many frustrated projects later, here is his first conventional feature. He is good with actors, good with his camera and determined to take the grade-zilch exploitation film and bend it to his own vision. Within the limits of the film’s possibilities, he has succeeded.”

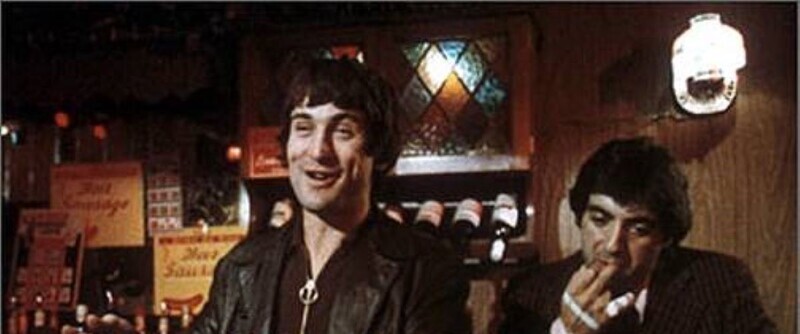

“Mean Streets”

“Charlie walks through the movie seeking forgiveness–from his Uncle Giovanni (Cesare Danova), who is the local Mafia boss, and from Teresa, his best friend Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), the local loan shark Michael (Richard Romulus) and even from God. He wants redemption. Scorsese, whose screenplay has autobiographical origins, knows why Charlie feels this way: He knows in his bones that the church is right, and he is wrong and weak. Although he is an apprentice gangster involved with men who steal, kill and sell drugs, Charlie’s guilt centers on sex. Impurity is the real sin; the other stuff is business.”

“Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore”

“The movie has been both attacked and defended on feminist grounds, but I think it belongs somewhere outside ideology, maybe in the area of contemporary myth and romance. There are scenes in which we take Alice and her journey perfectly seriously, there are scenes of harrowing reality and then there are other scenes (including some hilarious passages in a restaurant where she waits on tables) where Scorsese edges into slight, cheerful exaggeration. There are times, indeed, when the movie seems less about Alice than it does about the speculations and daydreams of a lot of women about her age, who identify with the liberation of other women, but are unsure on the subject of themselves.”

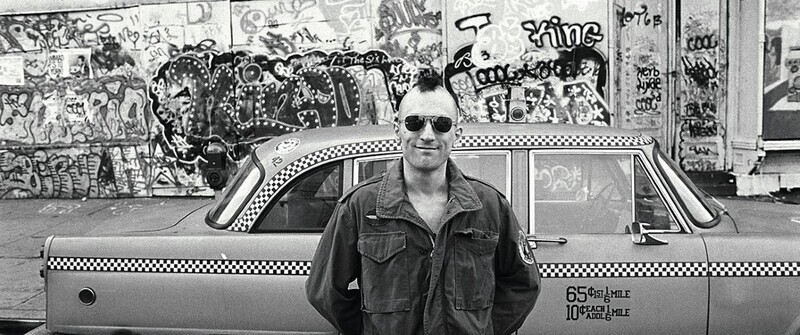

“Taxi Driver”

“This utter aloneness is at the center of “Taxi Driver,” one of the best and most powerful of all films, and perhaps it is why so many people connect with it even though Travis Bickle would seem to be the most alienating of movie heroes. We have all felt as alone as Travis. Most of us are better at dealing with it.”

“The Last Waltz”

“In “The Last Waltz,” we have musicians who seem to have bad memories. Who are hanging on. Scorsese’s direction is mostly limited to closeups and medium shots of performances; he ignores the audience. The movie was made at the end of a difficult period in his own life, and at a particularly hard time (the filming coincided with his work on “New York, New York”). This is not a record of serene men, filled with nostalgia, happy to be among friends.”

“New York, New York”

“Martin Scorsese’s “New York, New York” never pulls itself together into a coherent whole, but if we forgive the movie its confusions we’re left with a good time. In other words: Abandon your expectations of an orderly plot, and you’ll end up humming the title song. The movie’s a vast, rambling, nostalgic expedition back into the big band era, and a celebration of the considerable talents of Liza Minnelli and Robert De Niro.”

“Raging Bull”

““Raging Bull” is the most painful and heartrending portrait of jealousy in the cinema–an “Othello” for our times. It’s the best film I’ve seen about the low self-esteem, sexual inadequacy and fear that lead some men to abuse women. Boxing is the arena, not the subject. LaMotta was famous for refusing to be knocked down in the ring. There are scenes where he stands passively, his hands at his side, allowing himself to be hammered. We sense why he didn’t go down. He hurt too much to allow the pain to stop.”

“The King of Comedy”

“Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy” is one of the most arid, painful, wounded movies I’ve ever seen. It’s hard to believe Scorsese made it; instead of the big-city life, the violence and sexuality of his movies like “Taxi Driver” and “Mean Streets,” what we have here is an agonizing portrait of lonely, angry people with their emotions all tightly bottled up. This is a movie that seems ready to explode — but somehow it never does.”

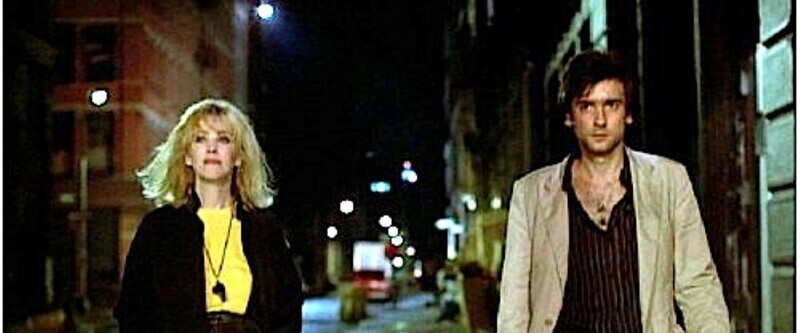

“After Hours”

“With different filmmakers and other actors, the film might have played more safely, like “Adventures in Babysitting.” But there is an intensity and drive in Scorsese’s direction that gives it desperation; it really seems to matter that this devastated hero struggle on and survive. Scorsese has suggested that Paul’s implacable run of bad luck reflected his own frustration during the “Last Temptation of Christ” experience.”

“The Color of Money”

“If this movie had been directed by someone else, I might have thought differently about it because I might not have expected so much. But “The Color of Money” is directed by Martin Scorsese, the most exciting American director now working, and it is not an exciting film. It doesn’t have the electricity, the wound-up tension, of his best work, and as a result I was too aware of the story marching by.”

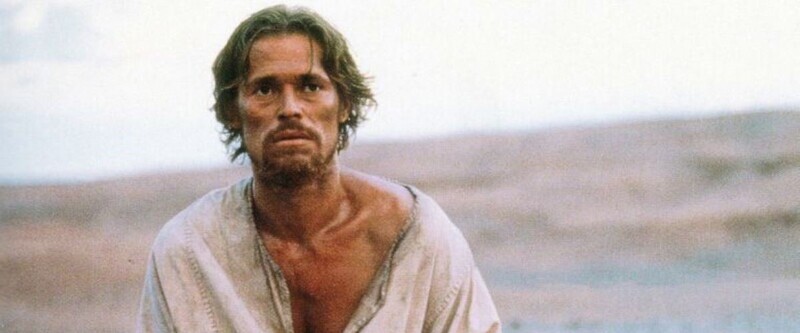

“The Last Temptation of Christ”

“I am left after the film with the conviction that it is as much about Scorsese as about Christ. In his films, he performs miracles, but for years could be heard to despair that each film would be his last. The Roman Catholic Church was for him like a heavenly father to whom he had a duty, but did not always fulfill it. These speculations may be wild and unfounded, ideas I am taking to him rather than finding in him, but particularly during Scorsese’s earlier years I believe the church played a larger role in his inner life than was generally realized. Talking with me after one of his divorces, he said, “I am living in sin, and I will go to hell because of it.” I asked him if he really, truly believed that. “Yes,” he said, “I do.””

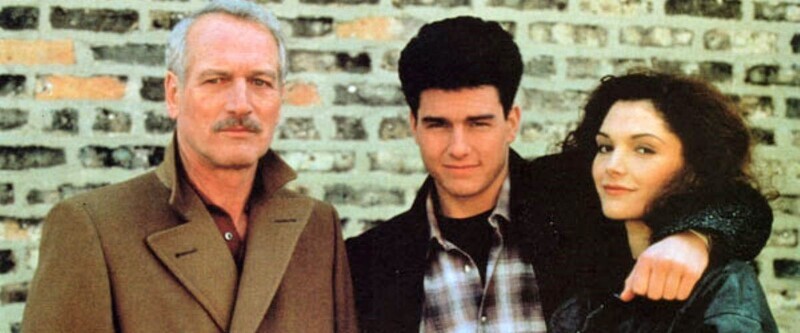

“Cape Fear”

““Cape Fear” is impressive moviemaking, showing Scorsese as a master of a traditional Hollywood genre who is able to mold it to his own themes and obsessions. But as I look at this $35 million movie with big stars, special effects and production values, I wonder whether it represents a good omen from the finest director now at work.”

“The Age of Innocence”

“I recently read The Age of Innocence again, impressed by how accurately the screenplay (by Jay Cocks and Scorsese) reflects the book. Scorsese has two great strengths in adapting it. The first is visual. Working with the masterful cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, he shows a society encrusted by its possessions. Everything is gilt or silver, crystal or velvet or ivory. The Victorian rooms are jammed with furniture, paintings, candelabra, statuary, plants, feathers, cushions, bric-a-brac and people costumed to adorn the furnishings.”

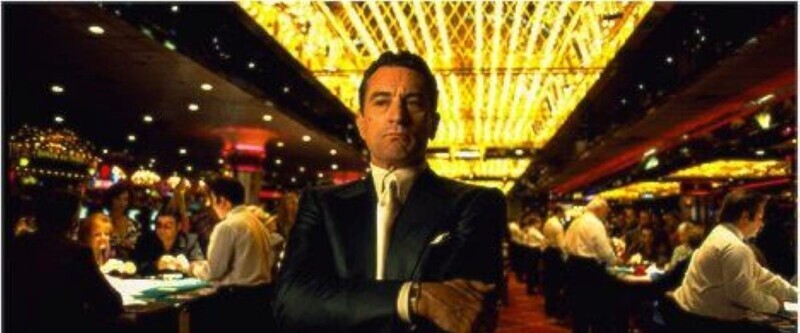

“Casino”

“Scorsese tells his story with the energy and pacing he’s famous for, and with a wealth of little details that feel just right. Not only the details of tacky 1970s period decor, but little moments such as when Ace orders the casino cooks to put “exactly the same amount of blueberries in every muffin.” Or when airborne feds are circling a golf course while spying on the hoods, and their plane runs out of gas and they have to make an emergency landing right on the green.”

“Kundun”

“That this film should come from Scorsese, master of the mean streets, chronicler of wiseguys and lowlifes, is not really surprising, since so many of his films have a spiritual component, and so many of his characters know they live in sin and feel guilty about it. There is a strong impulse toward the spiritual in Scorsese, who once studied to be a priest, and “Kundun” is his bid to be born again.”

“Bringing Out the Dead”

“To look at “Bringing Out the Dead”–to look, indeed, at almost any Scorsese film–is to be reminded that film can touch us urgently and deeply. Scorsese is never on autopilot, never panders, never sells out, always goes for broke; to watch his films is to see a man risking his talent, not simply exercising it. He makes movies as well as they can be made, and I agree with an observation on the Harry Knowles Web site: You can enjoy a Scorsese film with the sound off, or with the sound on and the picture off.”

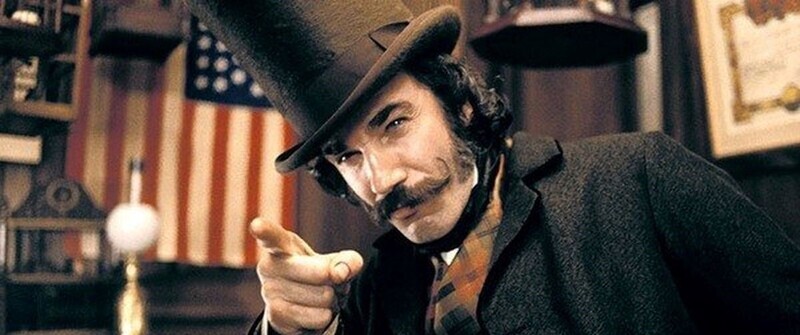

“Gangs of New York”

“The vivid achievement of Scorsese’s film is to visualize this history and people it with characters of Dickensian grotesquerie. Bill the Butcher is one of the great characters in modern movies, with his strangely elaborate diction, his choked accent, his odd way of combining ruthlessness with philosophy. The canvas is filled with many other colorful characters, including a pickpocket named Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz), a hired club named Monk (Brendan Gleeson), the shopkeeper Happy Jack (John C. Reilly), and historical figures such as William “Boss” Tweed (Jim Broadbent), ruler of corrupt Tammany Hall, and P.T. Barnum (Roger Ashton-Griffiths), whose museum of curiosities scarcely rivals the daily displays on the streets.”

“The Aviator”

“”The Aviator” celebrates Scorsese’s zest for finding excitement in a period setting, re-creating the kind of glamor he heard about when he was growing up. It is possible to imagine him wanting to be Howard Hughes. Their lives, in fact, are even a little similar: Heedless ambition and talent when young, great early success, tempestuous romances and a dark period, although with Hughes it got darker and darker, while Scorsese has emerged into the full flower of his gifts.”

“No Direction Home”

“But what was happening inside Dylan? Was he the jerk portrayed in “Don’t Look Back”? Scorsese looks more deeply. He shows countless news conferences where Dylan is assigned leadership of his generation and assaulted with inane questions about his role, message and philosophy. A photographer asks him, “Suck your glasses” for a picture. He is asked how many protest singers he thinks there are: “There are 136.””

“The Departed”

“Most of Martin Scorsese’s films have been about men trying to realize their inner image of themselves. That’s as true of Travis Bickle as of Jake LaMotta, Rupert Pupkin, Howard Hughes, the Dalai Lama, Bob Dylan or, for that matter, Jesus Christ. “The Departed” is about two men trying to live public lives that are the radical opposites of their inner realities. Their attempts threaten to destroy them, either by implosion or fatal betrayal. The telling of their stories involves a moral labyrinth, in which good and evil wear each other’s masks.”

“Shine a Light”

“Martin Scorsese’s “Shine a Light” may be the most intimate documentary ever made about a live rock ‘n’ roll concert. Certainly it has the best coverage of the performances onstage. Working with cinematographer Robert Richardson, Scorsese deployed a team of nine other cinematographers, all of them Oscar winners or nominees, to blanket a live September 2006 Rolling Stones concert at the smallish Beacon Theatre in New York. The result is startling immediacy, a merging of image and music, edited in step with the performance.”

“Shutter Island”

“This movie is all of a piece, even the parts that don’t appear to fit. There is a human tendency to note carefully what goes before, and draw logical conclusions. But — what if you can’t nail down exactly what went before? What if there were things about Cawley and his peculiar staff that were hidden? What if the movie lacks a reliable narrator? What if its point of view isn’t omniscient but fragmented? Where can it all lead? What does it mean? We ask, and Teddy asks, too.”

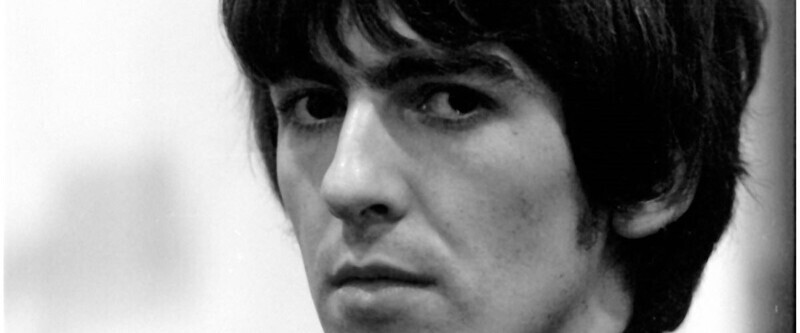

“George Harrison: Living in the Material World”

“All of this, and a great deal more, is covered in this respectful film. This is a more objective, less personal documentary than Scorsese usually makes. Considering its length, there isn’t much concert footage, and it focuses on archival interviews with George, news footage, and an impressive selection of talking heads.”

“Hugo”

“”Hugo” is unlike any other film Martin Scorsese has ever made, and yet possibly the closest to his heart: a big-budget, family epic in 3-D, and in some ways, a mirror of his own life. We feel a great artist has been given command of the tools and resources he needs to make a movie about — movies. That he also makes it a fable that will be fascinating for (some, not all) children is a measure of what feeling went into it.”

“The Wolf of Wall Street” (by Matt Zoller Seitz)

“Scorsese and Winter aren’t shy about drawing connections between Belfort’s crew and the thugs in Scorsese’s mob pictures. Those mob films are addiction stories, too. “Wolf of Wall Street” showcases Belfort Henry Hill-style, as if he were an addict touring the wreckage of his life in order to confess and seek forgiveness; but like a lot of addicts, as Belfort recounts the disasters he narrowly escaped, the lies he told and the lives he ruined, you can feel the buzz in his voice and the adrenaline burning in his veins. You can tell he misses his old life of big deals and money laundering and decadent parties, just as Hill missed busting heads, jacking trucks, and doing enough cocaine to make Scarface’s head explode.”

“Silence” (by Matt Zoller Seitz)

“Scorsese has been here before, in one sense or another—not just in straightforwardly theological dramas such as “Kundun” and “The Last Temptation of Christ,” but in his crime pictures and thrillers as well. The entire running time of “Silence” could be the self-flagellating fantasy of the young hoodlum hero of Scorsese’s 1973 breakthrough “Mean Streets” as he holds his hand over a flame (the title character in “Taxi Driver” did the same thing), and the terrors visited upon the priests and their flock are sadistic enough to have come straight from the reptile brain of Max Cady in “Cape Fear,” a devil or demon figure who exists to punish people for the sins of weakness, hypocrisy and pride. But “Silence” foregrounds such things in the manner of a parable that is not intended to lead the listener to a single realization but to stimulate thought and emotion.”

“Rolling Thunder Revue” (by Matt Zoller Seitz)

“Is Scorsese trying to create his own, epically scaled answer to “This is Spinal Tap” or “Zelig”—a mock documentary integrating the real with the fictional, prompting audiences to question the distinctions between them? Maybe. “The Rolling Thunder Revue” starts with a snippet of a silent-era George Melies film of a magic trick and returns to it later, as if to signal that an aspect of illusion is built into the project. The collision of verified events and never-before-discussed anecdotes (some of which, like Congressman Tanner’s friendship with President Jimmy Carter, are obviously fabricated) undermines the veracity of everything in the story, like the anecdote about Rivera supposedly taking Dylan to see KISS and inspiring him to don Kabuki-inspired face paint.”

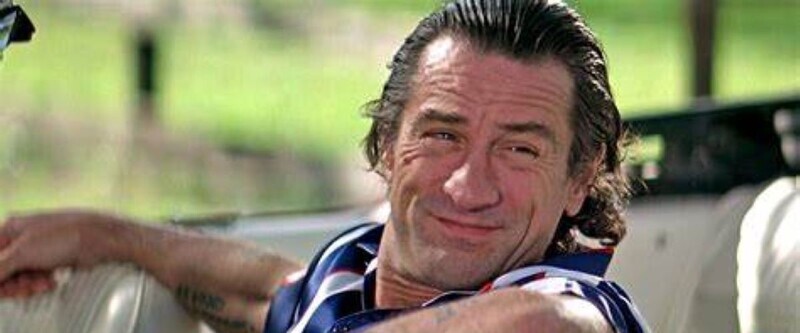

“The Irishman” (by Matt Zoller Seitz)

“Robert De Niro excels at playing closed-off, unreachable characters—hard men who might seem a bit dull if you met them for the first time, but have inner lives that they rarely let anyone see, and are mysteries to themselves. De Niro was 75 when he played yet another of those characters in Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman,” which feels like a summation of a rich subset of De Niro’s long career.”

“Killers of the Flower Moon” (by Brian Tallerico)

““Killers of the Flower Moon” may not be a traditional gangster picture, but it’s completely in tune with the stories of corrupt, violent men that Scorsese has explored for a half-century. And yet there’s also a sense of age in Scorsese’s work here, the feeling that he’s using this horrifying true story to interrogate how we got to where we are a hundred years later. How did we allow blood to fertilize the soil of this country? Scorsese and Roth took a book that’s essentially about the formation of the F.B.I. by way of the investigation into the Osage murders and shifted the storytelling to a more personal perspective for both Mollie and Ernest. Through their story, the film doesn’t just present injustice but reveals how intrinsic it was to the formation of wealth and inequity in this country. It hums with commentary on how this nonchalant violence against people deemed lesser pervaded a century of horror. The references to the Tulsa Massacre and the KKK aren’t incidental. It’s all part of the big picture—one of people who subjugate because it’s so easy for them to do so.”