Estus W. Pirkle: The Cinematic Evangelist

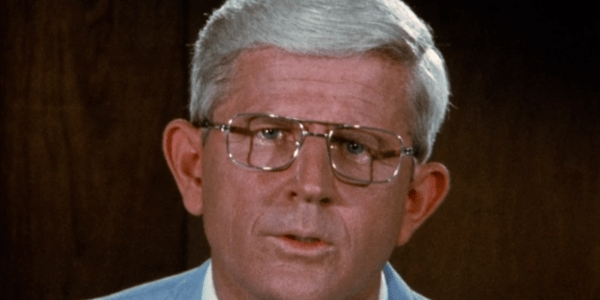

Estus Washington Pirkle was a Baptist preacher out of Mississippi and evangelist of the “turn or burn” variety that prized quantity of conversions over the quality of conversions. He was far from the only evangelist to hold the same approach to bringing souls to the kingdom of the Christian God, however, he may the only one who would seek to collaborate with a director largely known for exploitation films. Ron Ormond had spent most of his career making westerns and exploitations flicks like The Vanishing Outpost (1951) and Girl from Tobacco Row (1966). His wife, June Ormond, a former vaudeville singer/dancer, would partake in much of the later production efforts.

On the way to a screening of Girl from Tobacco Row, Ron, June, and their son, Tim, would crash in a field near Nashville, TN, in Ron’s single-engine airplane. Their epistemology of reality and what was important in this world would dynamically shift in the aftermath of the crash. The Ormonds’ conversion to Christianity, one could say, was more of a “burn then turn.” Yet it would be this event that would instigate the formation of The Ormond Organization in Nashville dedicated to the cinematic spread of the highly caveated gospel of fundamentalist theology, dispensational eschatology, and conservative politics. Now, the Ormonds, of course, might not have sided with every aspect of fundamentalist Christianity, but, in filming three cinematic Baptist sermons from Pirkle, they would end up burying any individual nuances within a collective group identity that was still in formation at this time.

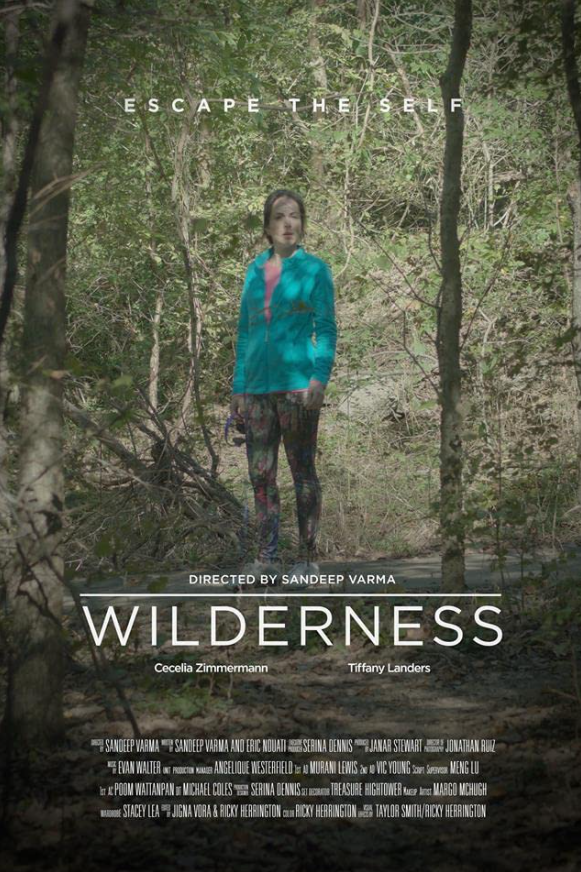

The three Pirkle-Ormond films that bookended the 1970s began with the If Footmen Tire You What Will Horses Do? (1971), three years later The Burning Hell came out, and then the decade was closed with 1977’s The Believer’s Heaven. While Ron Ormond had dedicated himself to Christ, this did not mean that his cinematic style would be altered. In fact, Ormond might be the first Godsploitation director. The infamous A Thief in the Night by Donald W. Thompson would not come out until a year after If Footmen Tire You…. One might say that Ormond’s first Pirkle film was Black Christmas to Thompson’s Halloween.

The Red in “Red Scare” Stands for Death

It is fitting though, for the time period, that If Footmen Tire You… subsumes anti-Communist propaganda within end-times theological rhetoric. Many fundamentalist pastors like Pirkle were premillennial dispensationalists who viewed the trajectory of history going progressively toward tribulation and catastrophe before “The Rapture” happens and Christ comes to rule for “1,000 years.” (By the way, there is only one section of scripture in 1 Thessalonians that literally speaks of something that could be construed as a rapture; the remainder is a theological interpretation developed from the whole text of the Bible). Having this particular eschatological (End Times) view of the world made it quite easy to engender terror in the hearts of Christians because every potential viewpoint that seemingly refuted Biblical dogma would lead to further guttering of the Christian faith. The end is nigh!

Yet it isn’t hard to find this general unease and terror towards the Communist threat in the midst of the Cold War even within the ranks of the non-religious. That fear of impending doom was the thing that many evangelists were banking on to get butts in the seats and souls saved. Once a pastor puts a religious overlay on a clear and present danger, the threat is no longer just physical, but eternal. If Footmen Tire You… maximizes this fear by showing horseback Communist forces going around average white American towns persecuting Christians, dispatching men, women, and children with bloody glee, and brainwashing those young people to give allegiance to Fidel Castro.

When we think of Christian cinema now, it is usually some version of Kirk Cameron facing some diluted, G-rated depiction of an actual sin instead of being, for instance, drowned by sexual addiction as Michael Fassbender is in Shame (2011). By the end of the film, he comes to “accept Jesus into his heart” and everything is fixed and blessed and perfect from then, on. This was not the case in the seventies. If Footmen Tire You… shows one boy getting rods shoved into his eardrums so he can no longer hear the gospel being preached. Another boy defies the orders of the Commissar to stomp on the picture of white Jesus and the Commissar takes a machete to his head. We actually witness the kid’s head roll onto the ground. Pirkle means business when he says that Communism will destroy America. Not even kid beheadings are taboo to the Communists!

Fear Him Which is Able to Destroy Both Soul and Body in Hell

The common ties between the first Pirkle-Ormond collaboration and the second, The Burning Hell (1974), is the low-budget violence and gore and the focus on a wayward person who happens into the congregation of Estus Pirkle while he is preaching and ends up going to the altar to accept Jesus. While Communism will most assuredly make your life here on earth a living hell, according to Pirkle, not even that can compare to the fiery torments of hell which will destroy both body and soul.

While hell is most assuredly terror-inducing enough, Pirkle’s judgment seems to be on the progressive strains of Christianity that were beginning to come into vogue. These versions of Christianity saw hell as something that we, humans, created here on Earth. They didn’t believe in a literal hell or eternal torment or perhaps even Satan. Our wayward character is played by Ormond’s son, Tim, who has been fooled into this new progressive Christianity until his religious cohort dies in a gory motorcycle crash where his head, too, is severed from his body in full view. Tearful and grief-stricken, the young man comes into Pirkle’s service—literally right after the wreck, we assume he left the mangled body there without notifying anyone. He walks down the aisle as Pirkle steps down from his lectern and comforts the young man by assuring him his friend probably is in a real, literal hell, but he could save his own soul before it is too late. Talk about pastoral counseling.

From this point on, we hear Pirkle’s sermon of hell and damnation and we witness his words being brought to life. The film shifts from Biblical times where we visit a handful of classic villains to witnessing their torment in hell which, in the imagery of Ormond and Pirkle, consists of a black void of a background with flames here and there throughout the abyss. Its inhabitants are filthy, perhaps singed, and either crying out in pain or re-enacting their mortal sins on other inhabitants of hell. The wayward son of The Burning Hell visualizes himself within this landscape and does not like what he sees. This fear is what drives him to the altar. This fear is what drove “turn or burn” evangelism for years within American society. Within the imaginaries of mid-to-late 20th-century Christian evangelism, the central reason to accept Christ as Savior was to save yourself. A perfect mirror image of American individualism and bootstrap theology.

I’ve Got Two Tickets to Paradise

In the conclusion of the Pirkle-Ormond collaborations, The Believer’s Heaven, we find what is perhaps the least interesting version of evangelical propaganda. Is it because the focus is on something positive instead of negative? Possibly. Is it because a majority of projections on what Heaven will look like and consist of are terribly lacking in imagination and substance? Yes, very much so. It is hard to enact b-roll footage of gore and blood when the subject is something that transcends worldly concerns and finds its residents in a place where there are no tears, sorrows, or grief. The Believer’s Heaven ends up being more of a prototype of the more contemporary Christian films than it does being a continuation of the much more fascinating Godsploitation schlock-fest films of the seventies.

Pirkle, who seemingly recognizes the lack of urgency that this final film has, ends up retreading his old stomping grounds of hell and damnation before the film finishes as a reminder that either of these destinations is just as likely as the other for your soul. The only other negative images we are shown take place at the beginning of the film when we are told about natural disasters in a South American country where houses are buried underneath stones from a volcano eruption. The camera pans across trenches of “dead” South American men, women, and children—though you can still see the actors breathing in the shots. These images are placed in opposition to the hyper-modernist cloud condos of heaven where white person after white person enters into the triangular gate of heaven to their own deluxe resort mansion. The subtext ultimately screaming that only white people go to heaven and all the minorities die brutal deaths and go to hell because they either didn’t know the gospel or didn’t accept Jesus into their heart.

The Believer’s Heaven has all of the intrigues of a filler episode of The Love Boat or Fantasy Island. That is until we get to the strange moment where it seems that Ormond took a note from the book of Tod Browning and decided to liven the scenery up by exploiting differently-abled bodies as a reminder, I guess(?), of the promise that heavenly resurrection bodies will erase the “imperfections” of our earthly bodies. We are given Little Evelyn Talbert (“54 years old and 32 inches tall”) who sings a gospel tune as well as a trio of singers with disabilities who join in on the song. There are so many theological assumptions about heaven that inhabit the film, that one assumes heaven as something that is as exclusive as that new night club down the street and ultimately erases our human histories of grief and difficulty—and the wisdom that came from it—in order to be younger, Malibu-model versions of ourselves sitting on the shores of a California beach.

The whiplash from the first two films to the final film is a little too stark to the point of making all of the trial and tribulation from If Footmen Tire You… and The Burning Hell gratuitous. Especially if all we really have to do is say the words, “I accept Jesus into my heart” and be ushered into an über-rich and white suburbia version of Heaven. Much like the anti-Communist propaganda of Pirkle’s first film, it seems that The Believer’s Heaven is just pro-Capitalist propaganda. Once again, a mirror image of American values in religious cinematic form.

Conclusion: I Hate All Your Show

“I hate all your show and pretense—the hypocrisy of your religious festivals and solemn assemblies…Instead, I want to see a mighty flood of justice, an endless river of righteous living” (Amos 5: 21 & 24 NLT).

As someone who tends to love horror and exploitation films, there is an element of schlocky entertainment that can be had at the expense of these films. As someone who is a trained historian, these films give us an insight into a specific time period of American history that soaks in the fears and concerns that plagued the country. However, as someone who identifies as a Christian himself, watching these three films all at once helps me understand why people don’t want to be Christian, why they don’t want to be religious in any sense of the word. If all the claims of the Biblical Christ become soundbites or bumper stickers for people who seek to use faith as a means to gain power, prestige, money, or simply a number of converts at any one revival, then I, too, would give up the faith.

The faith displayed in the collaborations between Pirkle and Ormond are mere shadows, cardboard cut-outs of the real thing. If it wasn’t for the fact that Pirkle very clearly is using the gospel to further his own political beliefs, then there would be at least sincerity in his message to contend with even if the hearer ultimately didn’t agree. However, Pirkle ends up becoming a propagandist for a certain political version of Christianity that, unfortunately, we all know too well and has led to the faith being depleted of its witness. The “turn or burn” evangelical mentality has its proponents and is not without its conversion successes—just look at Alice Cooper—but, as a whole, fear and individualistic comfort and salvation can only go so far in the face of the hurt and injustice of others in this world. Like the book of Amos speaks about, justice, too, is important to the message of Christianity, a message, unfortunately, absent from the cinematic evangelism of Estus Pirkle and Ron Ormond.

What are your thoughts on Estus Pirkle and Ron Ormond11? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!